Fossils show evidence of earliest moving creatures

Researchers at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) have helped uncover the earliest evidence ever found of organisms capable of movement

by Chris Putnam

Researchers at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) have helped uncover the earliest evidence ever found of organisms capable of movement.

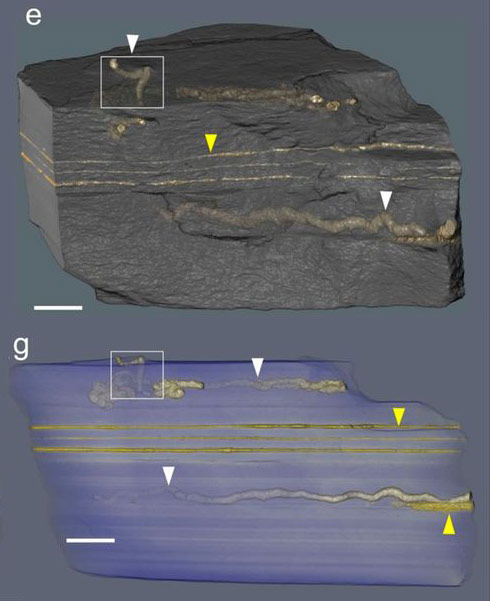

In a paper published this week, an international team of scientists reported the discovery of string-shaped fossils they believe to be trails left by tiny creatures that wriggled through mud 2.1 billion years ago.

The discovery suggests that some lifeforms on Earth were able to move themselves about 1.5 billion years earlier than previously thought.

Dr. Luis Buatois (PhD) and Dr. Gabriela Mángano (PhD), both professors in the geological sciences department of USask’s College of Arts and Science, are co-authors on the paper.

“This is by far the most challenging material we have ever studied. As soon as we looked at the specimens, we realized what was at stake,” said Buatois.

The strange fossils forced the researchers to consider explanations that could rewrite large portions of the timeline of life on Earth.

Similar structures have been found in rocks in the past, but the evidence they were made by very ancient lifeforms has never been as strong as this time, said Mángano. Using CT scans, the researchers were able to create highly detailed 3D reconstructions of the structures, and found “compelling” similarities to fossil burrows in younger rocks.

The volume of fossils in this case also makes for strong evidence, said Mángano. “We have a large collection of specimens and it is clear that we are looking at some recurrent patterns, not just a weird-looking curiosity.”

The researchers aren’t sure what the creatures responsible for the trails looked like, but suggest they might have been slug-like organisms, similar to slime moulds, that migrated through the mud in search of food.

The fossils were found in a deposit in Gabon, Africa, where evidence was previously discovered of the earliest colonial organisms—single-celled lifeforms that lived in colonies.

The location offers the “perfect geologic context to search for early life evidence,” said Mángano. The superbly preserved ancient environment there gives a view into a short and unique period of evolutionary history signaled by a rapid increase in oxygen.

The research is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.