Remembering a USask computing pioneer

Dr. Kathleen Booth (PhD) invented some of the technologies that make computers possible

By Chris Putnam

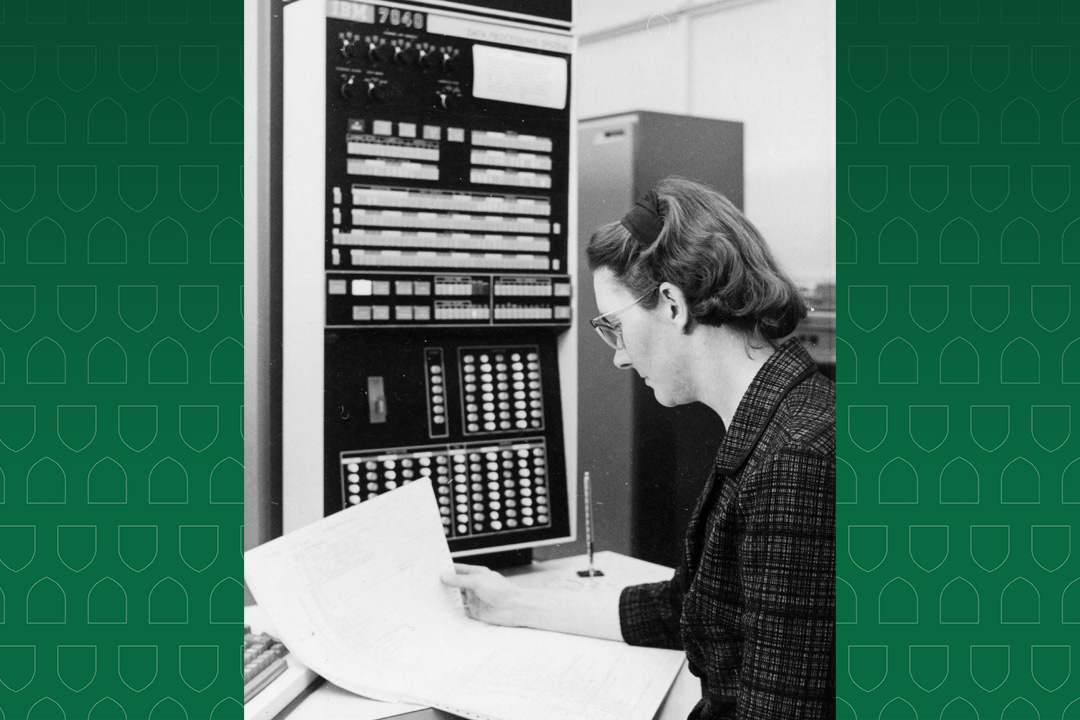

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly identified an image of Deanna Gupta as Kathleen Booth.

The recent passing of an early University of Saskatchewan (USask) computer scientist has brought renewed attention to her pioneering achievements.

Dr. Kathleen Booth (PhD), who died this fall at the age of 100, is credited with several of the innovations that made the Information Age possible. While working in the United Kingdom in the 1940s and 50s, she was the first to invent assembly language, wrote one of the first books on programming and helped create an algorithm fundamental to billions of computer processors today.

Yet during her time as a researcher at USask from 1962–72, few people were aware of her accomplishments.

“She was really modest. She didn’t say anything about her past contributions to the development of computers,” said Dave Bocking, a retired laboratory manager in the USask Department of Computer Science who took a course from Booth around 1971. “It was only in later years that I came to know what achievements she and her husband had made in their careers just after the Second World War and through the 50s. They were really, really innovators, but we never knew that.”

Booth worked at USask as a research fellow in the College of Arts and Science’s Department of Mathematics and later as a founding faculty member of the Department of Computational Science (now called the Department of Computer Science). Her husband, Dr. Andrew Booth (PhD)—another computing pioneer—served as dean of the USask College of Engineering during the couple’s years in Saskatoon.

The Booths are recognized with exhibits in several national science and computing museums in the U.K. When Kathleen passed away at the end of September 2022, newspapers including The Times and The Guardian wrote obituaries for her.

“(My parents) talked all the time both during and after our living in Saskatoon about how prairie people were the nicest and most friendly, helpful people they had ever met,” said Dr. Amanda Booth (DVM’83, MVetSc’86), Kathleen and Andrew Booth’s daughter and a graduate of USask’s Western College of Veterinary Medicine.

“I know they still spoke with affection about USask throughout their retirement, and they always appreciated their time there.”

Kathleen Booth was born Kathleen Britten in Worcestershire, England, in 1922. Starting in 1946, she worked as Andrew’s research assistant at Birkbeck College at the University of London. The Birkbeck group was the smallest of the British computer labs that launched after the Second World War.

“(Kathleen) was one of a very quiet group that weren’t intending to be making history. They were just working on things as they developed,” said USask computer science professor emeritus Dr. Rick Bunt (PhD), who took over Kathleen’s position when she left Saskatoon in 1972.

“What she was doing, she was doing before there was an industry, before there was an academic field. They were really early pioneers,” Bunt said.

jpg

Kathleen and Andrew were a potent team—he designed computers while she fabricated, assembled and programmed them. One of the Booths’ designs was commercialized by British Tabulating Machines and became the HEC (Hollerith Electronic Computer), the U.K.’s top-selling computer of the 1950s.

Creating assembly language

While working on one of their first computers in 1947, Kathleen created a symbolic language to simplify the process of programming the machine. This is now recognized as the world’s first assembly language.

An assembly language is a low-level programming language that translates human-readable instructions into the ones and zeros understood by computers. Its invention was a major leap forward in computer programming, which was previously done by inputting individual bits or even plugging and unplugging wires.

“Without (assembly language), programmers would have been faced with just a miserable task trying to program these things,” said Bocking.

Each computer design uses its own unique assembly language. Today, these languages have mostly been replaced by higher-level programming languages, but experienced programmers still turn to assembly when they need to maximize software performance or directly access certain hardware features.

“Without assembly language, I think computers would have been much less widely accepted. Assembly languages were the first way that normal people like us were able to start using computers,” said Bunt.

Working behind the scenes

Kathleen—who married Andrew and received her PhD in applied mathematics in 1950—is credited with several more milestones in computer history.

She and Andrew were cofounders of Birkbeck’s Department of Numerical Automation in 1957—thought to be the world’s first university computer science department. Her 1958 book Programming for an Automatic Digital Calculator was one of the first-ever books about computer programming.

She also had a hand in some achievements for which Andrew, who died in 2009, is usually given sole credit.

Kathleen helped Andrew create the world’s first magnetic storage device for a computer in 1947.This rotating metal drum was the ancestor of the spinning disks used in every floppy disk and hard drive in the decades that followed.

In 1950, Andrew published an elegant new algorithm for multiplying numbers in binary, greatly simplifying the calculations performed by computers. “Booth’s multiplier” is still built into virtually every processor sold today.

The Booths later recalled that the algorithm was created during a conversation between them over tea in a London café.

“Andrew was a very outgoing figure… where Kathleen was very quiet and kind of worked in the background. So it doesn’t surprise me at all that a lot of the credit for their joint accomplishments is given to Andrew. But they would admit they worked together constantly,” said Bunt.

A decade at USask

Kathleen and Andrew left Birkbeck to take up positions at USask in 1962.

The couple had become disillusioned with the politics and lack of support for science in Britain, said their daughter Amanda.

“They had offers from all over the world—many in the United States, New Zealand, etc.—but settled on Saskatchewan because Canada, and USask in particular, was at the forefront of scientific support and innovation.”

Kathleen worked part-time in the following years as she raised their two children and continued the work she began in England.

At USask, Kathleen was director of a National Research Council project investigating computer translation between French and English. The Government of Canada hoped that her automated translator could save costs when translating government documents and scientific papers.

Kathleen had given a demonstration of the technology as early as 1955 in what was likely the world’s first public display of machine translation of language. The concept is familiar to anyone who has used modern services such as Google Translate.

Kathleen also did early research into artificial neural networks at USask. Today, neural nets are at the heart of countless machine learning and artificial intelligence applications.

As one of the first faculty members of the Department of Computational Science, Kathleen helped develop the USask department’s original curriculum. She taught courses on programming and information storage.

“In retrospect, it’s sort of surprising to me and remarkable that—holy crow!—one of the founding faculty of the department was such an eminent innovator,” said Bocking.

The Booths left Saskatchewan in 1972 for Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ont., where Andrew became university president and Kathleen was an honorary professor of mathematics.

“They were here for a decade,” said Bunt, “and I think that’s something that we should be proud of.”