Formats

- Use 8 ½ x 11 inch (216 mm x 279 mm) white paper.

- Leave margins of one inch (2.5 cm) at the top, bottom, and sides unless your

instructor specifies otherwise. - Insert page numbers (numbers only, without “p.” or “pg.”) in the top right-hand corner and use

your last name as a “running header.” All word-processing programs have a function for inserting

headers (and footers) as well as page numbers. Your instructor may direct you to omit this header

on the first page of the essay. - Do not create a separate title page. Place your name, class and section number, instructor’s name,

and date submitted (not due date, if submission is late) on four separate lines at the top left of the

first page. Place the title on the line below, and centre it. Do not underline or put the title in bold

or in quotation marks; do not put it in a different size or style font. Begin the text of the essay on

theline below the title. - Indent the first sentence of every paragraph. Do not insert additional spaces between paragraphs.

- Titles of books and other works that are first published independently (e.g. plays, films,

pamphlets, journals) must be italicized, even when they appear in anthologies. Titles of shorter

works that typically first appear within larger works (e.g. stories, poems, essays, songs, newspaper

or journal articles) are put in quotationmarks. Do not use bold type, a different font, or all capitals

for titles of any sort. - Use a 12-point, standard font, such as Times New Roman. Double-space throughout, including

block quotations. Your instructor may ask you to print on one side of the paper only. - Fasten pages with a staple or a paperclip. Do not submit your essay in a binder, duo-tang, or

other document cover. - Be sure to back up the file of your completed essay. It is a good idea to keep a print copy as well.

- Canadian spelling is standard in Canada; British or American spelling is acceptable.

Whichever form of spelling you choose, use it consistently throughout your essay, except in

quotations, in which you should carefully follow the spelling of your source.

Standards for Composition

All essays should at a minimum meet the composition standards set for a student to passa first year English class. A student must by the end of such a class have shown reasonable competence in the

following skills:

- organizing an essay on a set topic, developing ideas logically and systematically, and

supporting these ideas with the necessary evidence, quotations, or examples; - organizing a paragraph;

- documenting essays using the Modern Language Association (MLA) style;

- writing grammatical sentences, avoiding such common mistakes as

- comma splices, run-on sentences, and sentence fragments

- faulty agreement of subject and verb or pronoun and antecedent

- faulty or vague reference (e.g. vague use of this, that, or which)

- shifts in person and number, tense, or mood

- dangling modifiers

- spelling correctly; and

- punctuating correctly.

Submission of Assignments

Essays are due on the dates specified. If you cannot avoid submitting an essay late, let your instructor know as far as possible in advance of the due date. You should also be able to give a good reason. There is usually a penalty forlate essays; consult the course outline for details. Unsubmitted assignments will at a minimum receive a zero in the calculation of the final grade. In some cases, an assignment must be submitted in order to pass the course. If the instructor has indicated in the course outline that failure to complete some or all assignments will result in failure in the course, a student with incomplete coursework will receive a final grade of no more than 49%, along with a grade comment of INF (Incomplete Failure).

Inclusive Language and Reconciliatory Writing Practices

The use of gender-neutral nouns such as police officer, firefighter, speaker has become standard,

as has representative instead of spokesman, and chair instead of chairman/woman/person. The use of he

to refer to a person of any gender identity and the use of man or mankind to refer to humanity in general

are no longer acceptable. While he or she has been used as an alternative in the past, the gender-neutral

singular pronoun “they” (“their,” “themself”) is now used for its universality. It is also used in

accordance with non-binary or genderqueer identities, queer Indigenous or Two Spirit identities, or when

someone’s gender identity is unknown or unspecified. In addition to the use of the singular “they,” non-inclusive language can be avoided by changing singular to pluralforms

| NON-INCLUSIVE | The successful student submits his or her essays on time. |

| INCLUSIVE (singular) | The successful student submits their essays on time. |

| INCLUSIVE (plural) | Successful students submit their essays on time. |

| NON-INCLUSIVE | The best way to help someone is to let him help himself. |

| INCLUSIVE (singular) | The best way to help someone is to let them help themself. |

| INCLUSIVE (plural) | The best way to help people is to let them help themselves. |

A wide range of singular personal pronoun sets (they/them/theirs; ze/hir/hirs; xe/xem/xyrs; etc.) may be used by authors or characters and should be respected.

In response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, the Department encourages

Reconciliatory Writing Practices. The sovereignty of Indigenous peoples is indicated by capitalizing the

words Indigenous, Aboriginal, or Native when they are used as nomenclatures for groups of nations and

peoples. References to “our native/aboriginal/indigenous people” are to be avoided, as are phrasings that imply that Indigenous people compose a single culture or hold a single set of beliefs, given the numerous, culturally distinct Indigenous nations and cultures in Canada, as well as in the US and throughout the world. Scholarly accuracy and integrity are not compatible with essentializing statements like “Indigenous people believe” or “Indigenous people think,” which are faulty claims, leading to unconvincing arguments as well as undermining efforts towards reconciliation.

Academic Honesty

Explanation

In literary essays you support your arguments with quotations from the text(s) about which you are writing. You may also incorporate material from scholarly works and other information sources. You must document the sources of any material you use, whether direct quotations, paraphrases ofothers’ arguments, opinions, facts, or figures. Accurate documentation acknowledges the work of others, and it makes your work more useful to readers, allowing them to find and use the sources you have worked with. Failure to document sources is plagiarism, a form of academic dishonesty.

You are plagiarizing if you present the words, thoughts, or research findings of someone else as if they were your own, or if you use material received or purchased from another person, or prepared by any person other than yourself. Exceptions are proverbial sayings such as “You can’t judge a book by its cover” and statements of common knowledge such as “Canada became a nation on July 1, 1867.” In general, it is also not necessary to document ideas and information conveyed in the classfor which the essay is being submitted, although you should document written materials located on or distributed through course sites (see Section 11k). If you use ideas conveyed in another class, documentthat lecture as you would any other source, using the system outlined in this handbook.

Note that even when your material is entirely your own, you may not submit it for credit in two different courses unless you have received permission from your instructors. Resubmission of your own work is another form of academic dishonesty.

Consequences

Instructors have two options in dealing with academic dishonesty, including plagiarism:

1) Informal procedure. If the instructor judges that a student has plagiarized inadvertently or because of a misunderstanding, and if the incident is confirmed to be a first offence, the instructor may determine, with the student, an appropriate remedy, such as agrade reduction and/or re-submission of the assignment. In this procedure, a form will be signed by both the instructor and student, and sent to the Office of the Associate Dean, Student Affairs, College of Arts and Science. This record is kept until the student graduates or for five years, whichever is shorter, and serves to alert the Dean’s office of repeated infractions.

2) Formal procedure. If an instructor believes the plagiarism is deliberate, if it is extensive, if the incident is determined to be a repeat offence, or if the student contests the allegation, the instructor will make a formal allegation of academic misconduct to the Associate Dean, Student Affairs, College of Arts and Science. A hearing will then be called at the College level. Ifthe committee finds that academic dishonesty has occurred, it will issue a penalty ranging from a zero on the assignment or examination to a zero for the course in question, to temporary suspension or permanent expulsion from the University.

Do not plagiarize; it is not worth the risk. If you have any doubt about what is and what is not allowed, talk to your instructor before you submit work. For more informationon, see the student academic integrity site.

Avoiding Plagarism

Plagiarism is avoided by careful quotation and documentation of all words and ideas taken from

secondary sources.

Example:

Original text, from an essay on Robinson Crusoe by Cameron McFarlane:

The journal begins, naturally, as a particularized account of the events in Crusoe’s daily life.

Plagiarism:

Crusoe’s journal begins as a particularized account of the events in his daily life.

Correct quotation and documentation:

As Cameron McFarlane points out, the early pages are “a particularized account of the events in

Crusoe’s daily life” (261).

Correct paraphrase and documentation:

Cameron McFarlane points out that the early pages of Crusoe’s journal describe his life in detail (261).

Work Cited

McFarlane, Cameron. “Reading Crusoe Reading Providence.” English Studies in Canada, vol. 21,

no. 3, 1995, pp. 257-67.

Documenting Sources: Overview of MLA Style

There are several different systems for documenting sources, developed by different academic disciplines to meet the needs and reflect the values of those disciplines. In English courses, you are required to use the Modern Languages Association (MLA) style. MLA style does not use footnotes or endnotes to cite sources. Sources are always cited in two stages:

- In-text citation:

Words taken from the text are indicated by double quotation marks, followed by parentheses containing the page number. A paraphrase of the text must also be followed by a parenthetical citation, as in the example below. Note that the author’s name is included in parentheses only when it has not been made clear in the preceding words or sentences:

ACCEPTABLE: One critic notes that Anna Jameson contributed to ethnography by transcribing Anishinaabe oral tales (Roy 13).

BETTER: Wendy Roy notes that Anna Jameson contributed to ethnography by transcribing Anishinaabe oral tales (13).

Do not put the title of the quoted work in the parentheses unless you are quoting from two different works by the same author (see Section 7b).

If you are quoting from a source that does not have page numbers but does have other explicitly numbered divisions, such as paragraphs, sections, chapters, or lines, provide the number(s) and the appropriate label, such as “par.” or “pars.” (e.g. par. 5), section numbers (“sec.” or “secs.”), or chapter numbers (“ch.” or “chs.”).

If you are quoting from a source that does not have page numbers or other numbered divisions, indicate the author’s name in parentheses only if it is not clear from the context. If it is clear, omit parenthetical citation following the quotation. Do not provide numbers that are not given in the source itself.

For in-text citations of time-based sources, such as audio and video recordings, indicate the time or range of times of the reference in question: that is, the hours, minutes, and seconds displayed on the media player, separated by colons: e.g. (Buffy 00:03:16-17). - A Works-Cited List

A works-cited list, at the end of your essay, will provide full bibliographic details for each source cited in the text (see Section 9).

Using Quotations

In English essays, you will be supporting your arguments about literary texts by choosing appropriate supporting quotations from the texts themselves. You may also use and be quoting from other print and digital sources, such as critical essays, reviews, letters, and reference works. All quotations must be integrated into your own writing. Here are some general rules:

- Introduce your quotations so that your reader knows why you have chosen them.

- Use brief quotations within your own sentences rather than long block quotations.

- Integrate the grammar of your quotations into the grammar of your sentences.

- Be accurate. Quote every word borrowed from your source, and do not change the original spelling, capitalization, or punctuation. If you must make changes, indicate you are doing so by using square brackets and/or ellipsis points (see Section 7e).

Note: All texts cited in Section 7 are documented in the works-cited list in Section 9d.

a. Introducing Quotations

If you introduce your quotation with a complete sentence, use a colon (:).

Example:

Robert Ross, in Timothy Findley’s The Wars, is often unsure of how to interpret his wounded companion’s words: “Harris said the strangest things—lying on his pillows staring at the ceiling” (95).

If you introduce the quotation with just a phrase, use (a) a comma or (b) no punctuation, depending on the structure of your sentence and of the quotation. Never use a semicolon (;) to introduce a quotation.

Examples:

(a)According to Robert, “Harris said the strangest things—lying on his pillows staring at the ceiling” (95).(b)Robert thinks Harris “said the strangest things—lying on his pillows staring at the ceiling” (95). (You would not put a comma between Harris and said if all the words of this sentence were of your authorship, so do not use a comma after Harris just because you are about to begin a quotation.)

b. Quoting More Than One Work by the Same Author

If you quote more than one work by a single author and have already established authorship, include an abbreviated form of the title before the page or line number in the parentheses. The point is to make it easy for your reader to find the source in the works-cited list. Note that there is only a space— no punctuation—between the title and the page number.

Example:

Laurence notes that the young Stacey Cameron leaves Manitoba for the west coast after a “business course in Winnipeg, then saving every nickel to come out here” (Fire-Dwellers 33). Hagar Shipley, however, is a married woman with a son when she leaves: “I packed our things, John’s and mine, in perfect outward calm, putting them in the black trunk that still bore the name Miss H. Currie” (Stone Angel 140).

c. Quoting Works by Different Authors

If you quote from different works by different authors, identify the sources either by using the authors’ names in your sentences (the best practice) or by placing the name before the page number in the parentheses. Note that there is only a space—no punctuation—between the author’s name and the page number.

Example:

Jane Austen is said to have fainted at the sudden news of the move to Bath (Honan 155), but a letter to Cassandra in early January shows Austen “more & more reconciled to the idea” of leaving Steventon (Austen 68).

d. Punctuating Quotations

A quotation within a quotation

If the material you quote includes a quotation or a title in quotation marks, use single quotation marks (‘ ’) within your own double ones (“ ”).

Example:

It is important to note that “fifty years after Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, India, ‘the Jewel in the Crown’ (Disraeli’s phrase), was cut in two” (Stallworthy 2018).

Final punctuation

Final punctuation belongs to your sentence, not the quotation. In most cases, you will drop the period from the original text and place one after the parentheses containing the page reference.

Example:

Robert watches Harris “lying on his pillows staring at the ceiling” (95).

However, if the quoted passage ends with a question mark or an exclamation point, include that original punctuation as well as placing a period after the parentheses.

Example:

Bates recalls wondering, “What if they were mad—or stupid?” (119).

e. Altering Quotations

Omitting words, phrases, or sentences

No quotation should be so altered as to change its original meaning. However, sometimes omitting a word, phrase, sentence, or sentences is necessary or desirable, usually for the sake of concision. You must indicate the omission by using three periods (ellipsis points), with a space before each and after the last. General rules are as follows:

- Do not use ellipsis points at the beginning of a quotation.

- Use ellipsis points at the end of the quotation only if the quoted words are taken from the middle of an original sentence, but form the end of your sentence.

- However you change the quotation, your sentence must be grammatically correct.

Examples:

Original, from Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility

Elinor joyfully profited by the first of these proposals, and thus by a little of that address which Marianne could never condescend to practise, gained her own end, and pleased Lady Middleton at the same time.

Ellipsis in the middle

By offering to help Lucy, Elinor “profited by the first of these proposals, . . . gained her own end, and pleased Lady Middleton at the same time” (171).

Ellipsis at the end

Elinor, using “a little of that address which Marianne could never condescend to practise, gained her own end . . .” (171).

Adding or substituting words or phrases

Use square brackets, i.e. [ ], to indicate that you have added or substituted something within a quoted passage to make the meaning clearer.

Example:

Using “a little of that address which Marianne could never condescend to practise, [Elinor] gained her own end, and pleased Lady Middleton at the same time” (171).

Adding emphasis

To emphasize a word or phrase in a quotation, use italics. In the parentheses following the quotation, put the words “emphasis added” after a semicolon following the page number.

Example:

Marianne begins to improve on “the morning of the third day” (318; emphasis added).

f. Quoting Prose

Short quotations from prose

Prose quotations of a word, a phrase, or up to four typed lines within your text appear within quotation marks, incorporated into your sentences.

Example:

That the gender socialization of Munro’s narrator is clearly far advanced becomes evident when she responds to her father’s dismissal of her as “only a girl” by reporting, “I didn’t protest that, even in my heart. Maybe it was true” (“Boys and Girls” 127).

Long quotations from prose

Prose quotations that would run five or more typed lines within your text are set off from the text as a

“block quotation,” as follows:

- Begin on a new line, indented from the left margin half an inch (1.25 cm) or approximately five spaces. Do not indent the first line an extra amount.

- Retain double spacing, do not change font size, and do not use quotation marks.

- If you are quoting two or more paragraphs, indent the first line of each quoted paragraph an additional quarter inch (.6 cm) or three spaces. Otherwise, do not further indent the beginning of a paragraph.

- Place final punctuation before the parenthetical page reference.

Example:

The storyteller of Leacock’s Sunshine Sketches expects readers to agree that Mariposa represents all

small towns in Canada:

I don’t know whether you know Mariposa. If not, it is of no consequence, for if you know

Canada at all, you are probably well acquainted with a dozen towns just like it.

There it lies in the sunlight, sloping up from the little lake that spreads out at the foot of the hillside on which the town is built. . . . People simply speak of the “lake” and the “river” and the “main street,” much in the same way as they always call the Continental Hotel “Pete Robinson’s” and the Pharmaceutical Hall “Eliot’s Drug Store.” But I suppose this is just the same in every one else’s town as in mine, so I need lay no stress on it. (13)

Note: No extra line space is inserted before or after block quotations. In general, a block quotation should be followed by further explanation and analysis, not a new paragraph.

g. Quoting Poetry

When quoting a poem, the convention is to cite line numbers only in the parentheses; the page number(s) will be given in your works-cited list. However, do not count line numbers if they are not provided in the source text you are quoting from. Instead, cite the page number(s) or use other division numbering, if it is available, such as canto number(s). If line numbers are provided, use the word “line” or “lines” in your first citation of the poem to indicate that the numbers relating to the source designate lines.

Short quotations from poetry

Quotations of up to three lines appear in quotation marks, incorporated into your sentences (example a). Use a forward slash (called a virgule) with a space on each side ( / ) to indicate a line break (example b).

Examples:

Original, from Margaret Atwood’s “Progressive Insanities of a Pioneer” (line numbers provided in source text):

He dug the soil in rows,

Imposed himself with shovels.

He asserted

into the furrows, I

am not random.

- Atwood’s pioneer “impose[s] himself with shovels” (line 11).

- Atwood’s poem makes writing and speech a metaphor for working the land: “He asserted / into the furrows” (12-13).

Long quotations from poetry

Quotations of four or more lines of poetry must appear in exactly the form of the original, set off

from your own text, as follows:

- Begin on a new line, indenting from the left margin half an inch (1.25 cm) or approximately five spaces. Retain double spacing, do not change font size, and do not use quotation marks.

- Follow the line breaks of the original, including spaces between stanzas.

- Include any final punctuation in the original text before giving the line numbers in parentheses. If the original ends with no final punctuation, reproduce it that way.

- If you omit words or phrases within or at the end of the quotation, indicate this omission with ellipsis points, as you do with prose (example a below). If you omit one or more lines of the poem, indicate this omission with a line of spaced periods approximately the length of a complete line of the poem (example b below).

- If there is no room for the parenthetical citation on the same line as the final line, put it on a new

line flush with the right margin of the page.

Examples:

(a) Evoking autumn leaves and addressing the wind, the speaker in “Ode to the West Wind” uses imagery of sickness and death:

Yellow, and black, and pale, and hectic red,

Pestilence-stricken multitudes: O thou, Who

chariotest to their dark wintry bed

The wingèd seeds, where they lie cold and low, Each like

a corpse within its grave . . . . (Shelley 4-8)

(b) The speaker in Gray’s poem describes a cat falling into a tub of

goldfishes:

Presumptuous Maid! With looks intent

Again she stretch’d, again she bent,

The slipp’ry verge her feet beguil’d,

She tumbled headlong in. (25-30)

h. Quoting Drama

When quoting from a play, cite in parentheses act, scene, and line numbers in that order if these are used in the text (example a). Otherwise, cite page numbers (example b).

Examples:

- Maecenas remarks on the turn in Antony’s fortunes, declaring, “Now Antony must leave her [Cleopatra] utterly” (2.2.234).

- In Doc, when Catherine says, “Bullshit, Daddy,” her father, Ev, replies, “Jesus Christ I hate to hear a woman swear like that” (126).

Verse passages from a play

If quoting up to three lines of verse from a play, use slashes to indicate line endings just as you do when quoting poetry (see Section 7g i). You can tell a passage is in verse if successive lines in a single speech do not run to the right margin.

Example:

Ariel’s first song in The Tempest is a summons to unseen spirits to dance: “Foot it featly here and there; / And, sweet sprites, the burden bear” (1.2.375-80).

For verse passages of more than three lines, follow the rules for long quotations of poetry (see Section 7g ii).

Prose passages from a play, film, or TV show

When quoting prose from a play, film or television show, no slashes are necessary.

Example:

In The Rover, Hellena makes clear her perspective: “I don’t intend that every he that likes me shall have me, but he that I like” (3.1.36-7).

Example:

Buffy’s promise that “there’s not going to be any incidents like at my old school” is obviously not one on which she can follow through (“Buffy” 00:03:16-17).

For prose passages of more than four typed lines, follow the rules for long quotations of prose (see Section 7f ii).

Dialogue from a play

When you quote dialogue between characters in a play, indent each character’s name half an inch (1.25 cm) or approximately five spaces from the left margin. Put the character’s name in capital letters, followed by a period, then the speech. Indent subsequent lines of that character’s speech an additional quarter inch (.6 cm) or three spaces. Start a new indented line for the next character’s speech. As with long quotations from poetry and prose, retain double spacing, do not change font size, and do not use quotation marks.

Example:

AMANDA. (Crossing out to kitchenette. Airily) Sometimes they come when they are least expected! Why, I remember one Sunday afternoon in Blue Mountain—(Enter kitchenette.)

TOM. I know what’s coming!

LAURA. Yes. But let her tell it. (8)

Endnotes and Footnotes

Endnotes and footnotes are used only for the addition of information or comments that would disrupt the flow of your main text, not for citation of your sources. They are generally of two kinds: content notes offer supplementary comment, explanation, or information; bibliographic notes contain additional references, references to opposing points of view, or evaluative comments on sources. These two kinds of information notes may be either footnotes or endnotes. Footnotes appear at the bottom of the page; endnotes appear at the end of essay, just before the list of works cited. You may use either style. In both cases, the notes are numbered consecutively throughout the paper. The text of the paper contains a raised arabic numeral (1, 2, 3 etc., not letters, roman numerals, or symbols) that corresponds to the number of the note.

Examples:

Content Note

A number of writers adopted the troublesome term classical to refer to the new aesthetic style.1

1 Wyndham Lewis was reluctant to part with the term, but by 1934 he declared it “strictly unusable” (Men 164-65).

Bibliographic Note

Jonathan Culler has been especially influential in his exposition of European literary theory.1

1 Also helpful are Eagleton 46-50, Lentricchia 128-30, and Norris 62-66.

The works cited list

A works-cited list for Requirements for Essays appears in Section 9c; it represents many commonly used types of sources. For examples listed by type of source, see Sections 10, 11, and 12. For further examples and explanations, see the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers (9th ed.), available in the Murray Library and for sale in the University Bookstore.

a. General Rules

- Start the list on a new page, under the heading Works Cited or, if only one work is listed, Work Cited. (If your list includes works you read but did not take any material from, the heading should be Works Cited and Consulted).

- List entries in alphabetical order by last name of author. If you used more than one work by the same author, list them alphabetically by title. After the first entry, use three dashes (---) and a period to indicate that you are repeating the name of the author (see the entries for Munro and Shakespeare in 9d). When no author is provided, the title determines the place of the entry in the works-cited list.

- The main words of titles and sub-titles are capitalized. Italicize titles of works that are self-contained or published on their own (e.g. a book, a play, a collection of essays). Use quotation marks to indicate the title of a source that is part of a larger work (e.g. a poem, an essay, a short story). When a source that is normally self-contained or independent appears in a collection or anthology, the work’s title remains in italics.

- Abbreviate publishers’ names using the following rules:

- Leave out articles (The, A, An, Le) and business abbreviations (Co., Ltd., Inc.).

- Shorten “University Press” to UP wherever the words appear in the publisher’s name: Oxford UP, U of Toronto P.

- With the exception of the abbreviations above, provide publishers’ names as given in the source, using standard capitalization, and including punctuation and words such as Books, House, Publishers.

- Periods are used after the name of the author, after the title of source, and at the end of the information for each container. Commas are used to separate information regarding the elements of the container(s).

- If the entry is more than one typed line, indent subsequent lines half an inch (1.25 cm) or approximately five spaces.

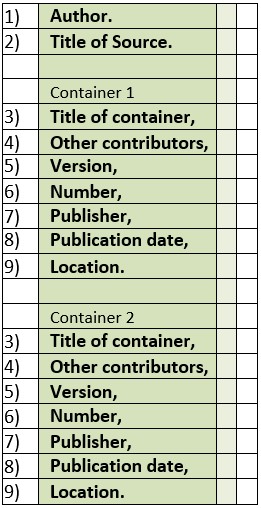

b. Citation Template

The citation template is a visual representation of how a works-cited list entry can be created. It indicates the elements possible for any entry. If the source you are citing is part of a larger whole such as an anthology, a journal, or a website, that larger whole can be regarded as a container. The container can itself be located within a larger container, just as back issues of a journal may be stored digitally through JSTOR.

c. Rules for Most Commonly Cited Sources

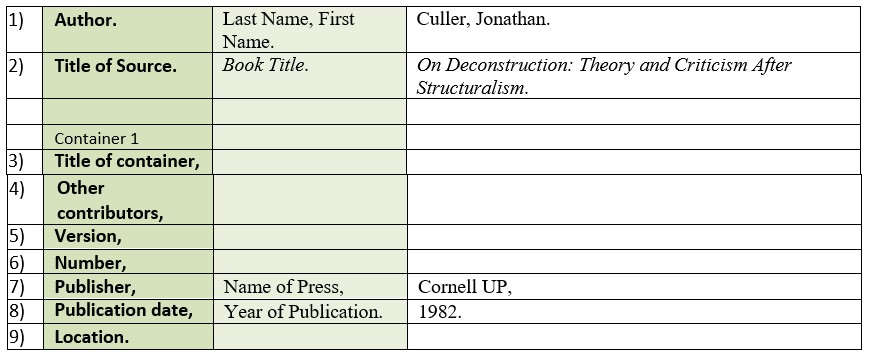

A book with one author

Give author (last name, first name), title (italicized), name of press, and year of publication (see the

template for punctuation between elements, and the entry for Culler in 9d).

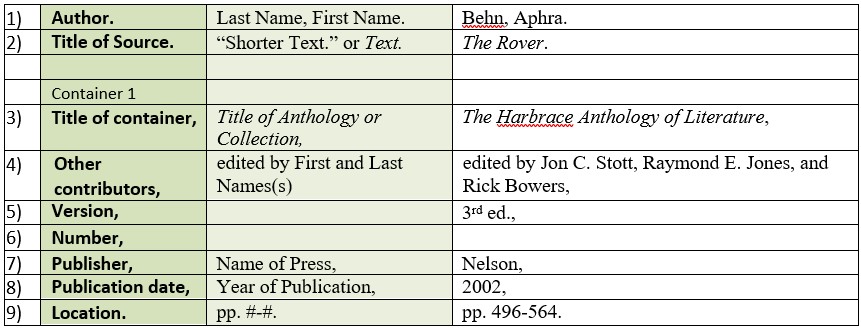

One or more works in an anthology or a collection

Provide the name of the author and the title of the source you have cited, then provide information about the larger work (or “container”) in which it appears: the title of the anthology or collection; the role and name(s) of the editor(s); name of publisher, year of publication; and the opening and closing pages of the source as found in the anthology. Preface the page number(s) with “p.” if the source is one page long or less, or “pp.” if it includes multiple pages (See the entry for Behn in 9d). If you cite two or more works from the same anthology, create one separate, complete entry for the anthology and cross-reference individual works to it. In the cross reference, list the work by author and title, then give only the last name(s) of the editor(s) followed by a comma and the inclusive page numbers of the work. (See the entries for Atwood and Lampman and their source, Brown, in 9d).

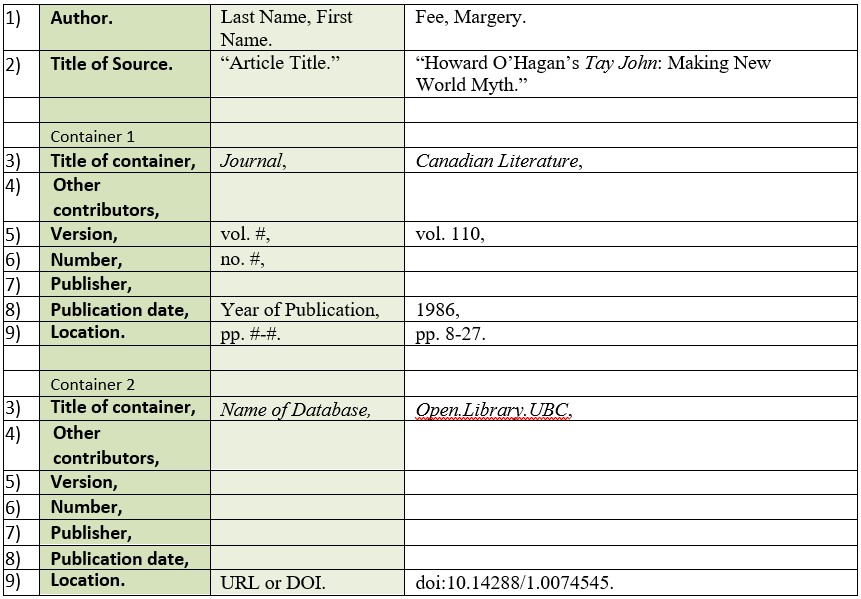

An article from a scholarly journal, newspaper, website, or database

Give author (last name, first name) and article title (in quotation marks), journal title (italicized),

volume number, issue number (if available), the date of publication (year and, if provided, month and day), and start and end page numbers prefaced with “pp.” to indicate that they are pages. (See the entry for McFarlane in 9d).

For journal articles and other materials accessed online, Container 2 is used to provide information on where the source can be located, including the name of the database, if applicable. While URLs are acceptable, DOIs (digital object identifiers) are preferable, as they represent stable links to the sources in question. (See the entry for Fee in 9d).

d. Example: Works-Cited List for Requirements for Essays

Works Cited

Atwood, Margaret. “Progressive Insanities of a Pioneer.” Brown, Bennett, and Cooke, p. 592.

Austen, Jane. Jane Austen’s Letters. Edited by Deirdre Le Faye, 3rd ed., Oxford UP, 1995.

---. Sense and Sensibility. Edited by Kathleen James-Cavan, Broadview Press, 2001.

Behn, Aphra. The Rover. The Harbrace Anthology of Literature, edited by Jon C. Stott,

Raymond E. Jones, and Rick Bowers, 3rd ed., Nelson, 2002, pp. 496-564.

“Buffy the Vampire Slayer: Unaired Pilot 1996.” YouTube, uploaded by Brian Stowe, 28 Jan. 2012,

www.youtube.com/watch?v=WR3J-v7QXXw. Accessed 28 Aug. 2017.

Brown, Russell, Donna Bennett, and Nathalie Cooke, editors. An Anthology of Canadian Literature in English. Revised and abbreviated edition, Oxford UP, 1990.

Culler, Jonathan. On Deconstruction: Theory and Criticism After Structuralism. Cornell UP,

1982.

Eagleton, Terry. Literary Theory: An Introduction. U of Minnesota P, 1983.

Evans, G. Blakemore, et al., editors. The Riverside Shakespeare. 2nd ed., Houghton-Mifflin, 1977.

Fee, Margery. “Howard O’Hagan’s Tay John: Making New World Myth.” Canadian Literature, vol.

110, 1986, pp. 8-27. Open.Library.UBC, doi:10.14288/1.0074545.

Findlay, Isobel M., et al., editors. Introduction to Literature. 4th ed., Harcourt Brace, 2001.

Findley, Timothy. The Wars. Penguin Books, 1982.

Gray, Thomas. “Ode on the Death of a Favourite Cat, Drowned in a Tub of Gold Fishes.”

Findlay et al., pp. 153-54.

Honan, Park. Jane Austen: Her Life. Ballantine Books, 1987.

Lampman, Archibald. “Heat.” Brown, Bennett, and Cooke, pp. 153-54.

Laurence, Margaret. The Fire-Dwellers. McClelland and Stewart, 1991.

---. The Stone Angel. McClelland and Stewart, 1982.

Leacock, Stephen. Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town. McClelland and Stewart, 1994.

Lentricchia, Frank. After the New Criticism. U of Chicago P, 1980.

Lewis, Wyndham. Men Without Art. Edited by Seamus Cooney, Black Sparrow Press, 1987.

McFarlane, Cameron. “Reading Crusoe Reading Providence.” English Studies in Canada, vol. 21, no. 3

1995, pp. 257-67.

Munro, Alice. “Boys and Girls.” Dance of the Happy Shades. McGraw-Hill, 1968, pp. 111-27.

Norris, Christopher. Deconstruction and the Interests of Theory. U of Oklahoma P, 1989.

Pollock, Sharon. Doc. Playwrights Canada Press, 1984.

Roy, Wendy. Maps of Difference: Canada, Women, and Travel. McGill-Queens UP, 2005.

Shakespeare, William. Antony and Cleopatra. Evans, pp. 1391-439.

---. The Tempest. Evans, pp. 1656-88.

Shelley, P.B. “Ode to the West Wind.” Findlay et al., pp. 173-76.

Stallworthy, Jon, ed. The Twentieth Century. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. General editors,

M.H. Abrams and Stephen Greenblatt, 7th ed., Vol. 2C., W. W. Norton, 2000.

Williams, Tennessee. The Glass Menagerie. New Directions Publishing, 1966.

Citation examples by type: print sources

For further examples and explanations, see the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers, 9th ed., available from the Murray Library, in print at the Reference Desk and online

- An Article in a Journal

McLoone, George H. “‘True Religion’ and Tragedy: Milton’s Insights in Samson Agonistes.” Mosaic, vol. 28, no. 3, 1995, pp. 1-29.

- A Book with One Author

Munro, Alice. Lives of Girls and Women. Penguin Books, 1990.

- A Book with One Author and an Editor

Shakespeare, William. The Tempest. Edited by Northrop Frye, Penguin Books, 1970.

- A Work in an Anthology or a Collection

King, Bruce. “Hookto.” All My Relations: An Anthology of Contemporary Canadian Native Fiction, edited by Thomas King, McClelland and Stewart, 1990, pp. 123-28.

- An Anthology or a Collection

For one or two editors, provide the names in the order they appear followed by “editor” or

“editors.” For more than two editors, you may use the editor whose name appears first, followed by “et al.,

editors” (meaning “and others, editors”).

Valdez, Luis, and Stan Steiner, editors. Azatlan: An Anthology of Mexican American Literature.

Vintage, 1972.

Lauter, Paul, et al., editors. The Heath Anthology of American Literature. 2nd ed., vol 1., D. C. Heath,

1994.

- A Work in a Course Readings Package

Mootoo, Shani. “Out on Main Street.” Course pack for English 444: Topics in Commonwealth and Postcolonial Literature, compiled by Susan Gingell, winter 2012, U of Saskatchewan.

- An Introduction, a Preface, a Foreword, or an Afterword

Drabble, Margaret. Introduction. Middlemarch, by George Eliot, Bantam Books, 1985, pp. vii-xvii.

- An Essay or Document from a Critical Edition

Mellor, Anne K. “Possessing Nature: The Female in Frankenstein.” Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley, edited by J. Paul Hunter, W. W. Norton, 1996, pp. 274-86.

- A Work in Translation

Carrier, Roch. The Hockey Sweater and Other Stories. Translated by Sheila Fischman, Anansi Press, 1979.

- An Anonymous Work

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Edited by J. R. R. Tolkien and E. V. Gordon, Clarendon Books, 1967.

- A Dictionary or Encyclopedia Entry

When citing well-known reference books, give only the edition used and the year of publication:

“Azimuthal, Adj.” The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed., 1989.

Details for less familiar reference books should be fully cited:

“Mouré, Erin.” The Feminist Companion to Literature in English. Edited by Virginia Blain, Isobel

Grundy, and Patricia Clements, Yale UP, 1990.

- The Bible

When documenting the use of scripture, provide an entry in your Works Cited list that indicates the edition of the Bible you are using. Provide the edition title or last name of the editor in your first parenthetical citation as well as the abbreviated name of the book and chapter and verse numbers. Subsequent citations can omit the name of the edition: e.g. (Authorized King James Version, John 12.4446), (Gen. 3.1-7).

The Bible. Authorized King James Version, Oxford UP, 1998.

- A Newspaper Article

Grange, Michael. “Yet More Snow as Winter Drags On, and On, and On.” Globe and Mail, national edition, 5 Apr. 1996, p. A6.

- A Magazine Article

Russell, Jim. “Pay the Piper: Arts Policy in Saskatchewan.” NeWest Review, Oct.-Nov. 1995, pp. 9-14.

- A Review

Carey, Barbara. “Her Brilliant Career.” Review of All You Get is Me: The Real Story of k.d. lang, by Victoria Starr. Books in Canada, vol. 23, no. 4, 1994, pp.

Citation examples by type: web sources (textual)

Follow the same practices for online sources as you would for any print source: identify the author(s), if indicated; the title of articles, posts, and/or website; the date the source was posted or published; and the name of the database through which you accessed the source (if you used one).

In addition, include the “location” of a web source, which is the URL, DOI, or permalink. If there is no DOI or permalink, copy and paste the URL directly from the address bar in your browser. Omit the protocol (usually http:// or https//) and the query string, if there is one (e.g.: /?query=pmla). If the URL runs more than three lines in your text, truncate it, but take care to preserve the essential information that your reader will need to locate the source.

For web sources lacking dates of publication, that may be regularly updated, or may be ephemeral, also provide the date on which you accessed the material.

Citation examples for some common types of web sources are given below. If you are not sure which type your source is, or if you are working with less common types of sources, consult a librarian or your instructor. For further examples and explanations, see the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers (9th ed.), available at the Murray Library.

A Journal Article in an Online DatabaseThe contents of many print-based journals are available through online full-text databases, and the articles will include the publication information for the print source. Provide the full citation information as you would for an article in a print journal (see 9b iii). Then add the title of the database (italicized), and the URL or DOI.

Note: The library subscribes to databases through suppliers, such as EBSCO, Infotrac, and Gale. Do not include the supplier in the citation. Commonly used full-text databases include JSTOR, Project Muse, and Academic Search Complete. These databases are interlinked through the “Find It” function. If you follow the link from one database to another, be sure to cite the database in which the article actually appears, not the one you linked from.

Carroll, Laura. “A Consideration of Times and Seasons: Two Jane Austen Adaptations.” Literature Film

Quarterly, vol. 31, no. 3, 2003, pp. 169-76. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43797118.

Rabb, Melinda. “The Secret Memoirs of Lemuel Gulliver: Satire, Secrecy, and Swift.” ELH, vol. 73, no, 2,

2006, pp. 325-54. Project Muse, doi:10.1353/elh.2006.0020.

An Article in an Online PeriodicalSome periodicals, including some scholarly journals, are published only online. These are either accessed directly or through databases as in the example above.

Conger, Syndy M. “Confessors and Penitents in M. G. Lewis’s The Monk.” Romanticism on the Net, no. 8,

November 1997. Projet Erudit, doi:10.7202/005768ar.

An Online Text with Print Publication DataJewett, Sarah Orne. The Country of the Pointed Firs. Houghton, 1910. Bartleby.com, 1999,

An Online Text within a Scholarly ProjectMarvell, Andrew. “To His Coy Mistress.” Representative Poetry Online, edited by N. J. Endicott, U of

Toronto, 2005, rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poems/his-coy-mistress.

A Scholarly ProjectVictorian Women Writers Project. General editors, Angela Courtney and Michelle Dalmau, Indiana U,

1995-2017, webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/vwwp/welcome.do.

An Online Dictionary or Encyclopedia“Hurdy-gurdy, N(1).” OED Online. Oxford UP, June 2021, www.oed.com/view/Entry/89551

“Fresco Painting.” Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 22 May.

2020 academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/fresco-painting/35374.

An Online Text with No Author Identified

“Dub Poetry.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 15 May 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dub_poetry.

A Newspaper Article Accessed OnlineBascaramurty, Dakshana. “Debate Escalates over Legacy of John A. Macdonald in Ontario Schools.”

The Globe and Mail, 24 Aug. 2017, beta.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/ontario-elementary-teachers-union-wants-john-a-macdonald-schools-renamed/article36076966

A Professional or Personal SiteDepartment of English Home Page. Department of English, U of Saskatchewan,

artsandscience.usask.ca/english/.

Banco, Lindsey. Faculty Page. Department of English, U of Saskatchewan,

artsandscience.usask.ca/profile/LBanco#/profile.

A Blog PostBertram, Chris. “Sitting in Limbo.” Crooked Timber, 4 Aug. 2021,

crookedtimber.org/2021/08/04/sitting-in-limbo/

Unpublished Course Material Posted on a Course Site“Defining Narrative.” English 113 (09): Reading Narrative, taught by Ella Ophir. Canvas, U of

Saskatchewan, fall 2020, canvas.usask.ca/courses/9045/pages/5-lecture-slides-for-module-1

Citation examples by type: audio, visual, and other media

An Image (Painting, Photograph, or Illustration)

Viewed in print or online

Bell, Richard. Life on a Mission. 2009, National Gallery of Canada,

www.gallery.ca/collection/artwork/life-on-a-mission

Thomas, Alma Woodsey. Peripheral Vision. 2017, A Big Important Art Book (Now with Women!), by

Danielle Krysa, Running Press, 2018.

Viewed in person

Pepper, Thelma. Evangeline’s Mother. 1993, Remai Modern, Saskatoon.

An E-mail or Text Message

These kinds of communications are treated as sources without titles; a description is provided instead. If you are the recipient you may refer to yourself as “the author.”

Dahl, Candice. Text message to the author. 13 Aug. 2021.

Smith, Steven Ross. E-mail to Susan Gingell. 9 Oct. 2006.

A Live Presentation (Lecture, Talk, Conference Presentation, or Speech)

Meek, Heather. “Of Wandering Wombs and Wrongs of Women: Hysteria in the Age of Reason.” 5 Mar.

2009, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon. Lecture.

A Film, DVD, or Video

Note: If a source such as a film, television episode, or live performance has many contributors, include the ones most relevant to your discussion.

The English Patient. Directed by Anthony Minghella, performance by Ralph Fiennes, Miramax, 1996. Hill,

Lauryn. “Motives and Thoughts.” Def Jam Poetry Session, 2005. YouTube, uploaded by

Transcendental Blackness, 30 Mar. 2010, www.youtube.com/watch?v=XUIg0LbYNyE.

Scott, Ridley, director. Blade Runner.1982. Performance by Harrison Ford, director’s cut, Warner

Bros.,1992.

A Live Performance

Twelfth Night. Written by William Shakespeare, directed by Will Brooks, Shakespeare on the

Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, 7 July 2017.

A Sound Recording

Bach, Johann Sebastian. The Two Violin Concertos. Performance by Gidon Kremer and Academy of St.

Martin-in-the-Fields Chamber Orchestra, Phillips, 1996.

A Television or Radio Program (Broadcast or Online)

“Beyond the Wall.” Game of Thrones, directed by Alan Taylor, written by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss,

season 7, episode 6, HBO, 20 August 2017.

“The Brains of Babes: Part 1.” Ideas, narrated by Jill Eisen, CBC/RadioCanada, 4 Mar. 2009. CBC player,