The observatory sundial

By Christopher Putnam (BA’07)

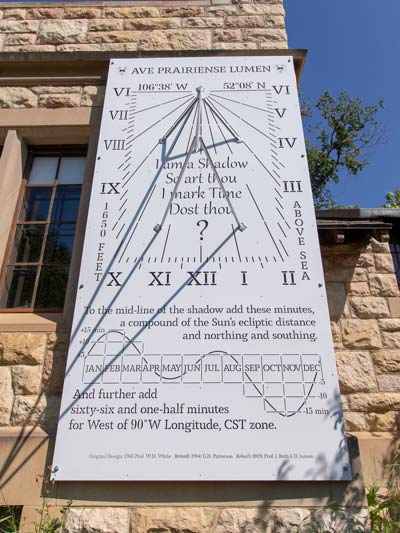

For five decades, a towering timepiece outside the University of Saskatchewan (USask) Observatory challenged visitors: “I am a Shadow / So art thou / I mark Time / Dost thou?”

True to the motto inscribed on its face, that one-of-a-kind sundial was lost to time. It weathered away, being rebuilt in 1984 before it was finally removed in the early 1990s.

In August 2019, a new 10-foot-tall replica of the sundial was installed at the observatory. The replacement features the original gnomon, or shadow caster.

College of Arts and Science astronomy instructor Dr. Daryl Janzen (BSc’04, MSc’08, PhD’12) led the project to replace the sundial. He said he has wanted to see the instrument return since first hearing about it as a student in the early 2000s.

“A sundial is a really cool feature that draws people’s attention to the movement of the Earth. And this was a really unique one that had been here for 50 years,” Janzen said.

The original custom-made sundial was designed and paid for by William H. White around 1945. White retired to Canada from a professorship at the University of London, coming to Saskatoon in 1942 to be near an observatory where he could pursue his astronomy hobby. He volunteered at the campus observatory for 18 years and was the first to open the facility’s doors to the public.

A classical scholar as well as a physicist, White sometimes helped in the physics department by grading papers submitted by engineering students. The eccentric scientist was known for leaving students detailed comments—most of them written in Latin.

White’s eclectic interests are reflected in the sundial’s design. The inscription at the top, in what White called “good enough prairie-dog-Latin,” is AVE PRAIRIENSE LUMEN. Roughly translated, it means “Hail light of the prairie.” The “I am a Shadow” motto was taken from a 17th-century sundial in Scotland.

The Department of Physics and Engineering Physics funded the new sundial, which was constructed with help from the university’s Physics Machine Shop and Digital Research Centre.

“As much as possible, we tried to keep it the same as the original,” said Department of Art and Art History faculty member Dr. Jon Bath (BA’97, MA’00, PhD’10), who designed the 2019 replica.

The new sundial differs from the previous versions in one important way. Instead of wood, it is made from resilient powder-coated aluminum.

“Our goal was to make something as permanent as we could,” said Janzen.

Cobalt-60 treatment at USask made medical history

By James Shewaga

This year marks a special 70-year anniversary for the University of Saskatchewan (USask), when researchers made medical history on campus and began a tradition of world-leading innovation that continues to this day.

Turn back time to 1951, when a team of remarkable researchers led by Dr. Harold Johns became the first in the world to build a cobalt-60 radiation therapy unit and the first to also successfully treat a cancer patient using the revolutionary treatment that would help save millions of lives around the world. That first cancer patient—a 43-year-old mother of four suffering from cervical cancer—would go on to live until the age of 90, with the original cobalt-60 unit used to treat 6,728 more patients over the next 21 years.

Johns’ original research team on the cobalt-60 unit—dubbed the “cobalt bomb” by members of the media—included graduate student Sylvia Fedoruk, a pioneering figure in medical science who would later become the university’s first female chancellor in 1986 and the province’s first female lieutenant-governor in 1988. Fedoruk (BA’49, MA’51, LLD’06) conducted the calibration of the unit, an 11-week process to define the precise radiation depth-dose measurements to treat cancer tumours.

“It is just a wonderful story and I think it’s fulfilling to feel that I was around for the start of it all,” said Fedoruk, in an interview for Cobalt-60 at 60: The Legacy of Saskatchewan’s Innovative Cancer Treatment.

Fedoruk was named one of the College of Arts and Science’s inaugural Alumni of Influence in 2009 and was also inducted into the Canadian Curling Hall of Fame. Her role in making medical history is documented in the new biography, A Radiant Life, by historian and College of Arts and Science alumna Dr. Merle Massie (BA’93, MA’98, PhD’11).

The original cobalt-60 machine is now on permanent display in Saskatoon’s Western Development Museum, a tribute to one of the first of many contributions the university has made to advancing medical research over the years.

“With its flair for trend-setting performance in medicine, Saskatchewan had led the way,” Fedoruk and Dr. Stuart Houston wrote in their 1995 book, A New Kind of Ray.

USask’s history of medical marvels helped lay the foundation for future innovation and research the world needs that continues today on campus at the Canadian Light Source (CLS) and the Sylvia Fedoruk Canadian Centre for Nuclear Innovation. The Fedoruk Centre oversees use of the university’s cyclotron—at the Saskatchewan Centre for Cyclotron Sciences—which produces medical isotopes for the province’s first PET-CT scanner that is used in cutting-edge cancer treatment. Meanwhile, the CLS—home to the country’s only synchrotron—employs a linear accelerator for research into producing medical isotopes for diagnosis and treatment.