Felicia Gay and Ruth Cuthand first met each other in 1999, when Gay was a student in a First Peoples art history course Cuthand was teaching at the University of Saskatchewan (USask).

Since then, over a period of more than 20 years, the USask alumni have worked together on several occasions—most recently on Beads in the blood, a survey exhibition of Cuthand’s artwork guest curated by Gay. The show, which opened on Jan. 22, 2021, was on display in College Art Gallery 1 and 2 on the USask campus until April 10, 2021.

Cuthand (BFA’83, MFA’92) said she was “really excited” when she first heard the concept for the exhibition, developed by curator Leah Taylor (BFA’04) and director jake moore of the University of Saskatchewan Art Galleries and Collection, and the idea of asking Gay (BA’04, MA’11) to guest curate it.

“Felicia’s great to work with—I’ve worked with her quite a bit—and it was really exciting to bring together a major overview of the work that I’ve done. I didn’t realize there was so much of it,” Cuthand said in a recent interview.

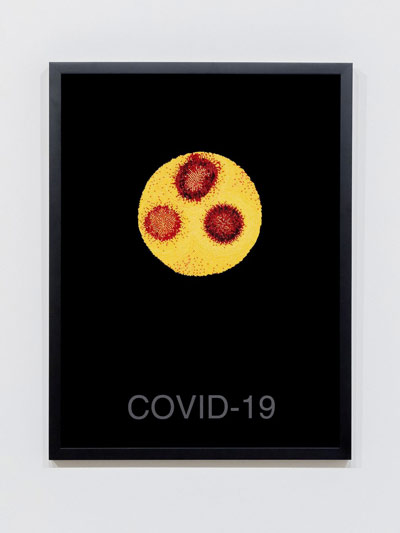

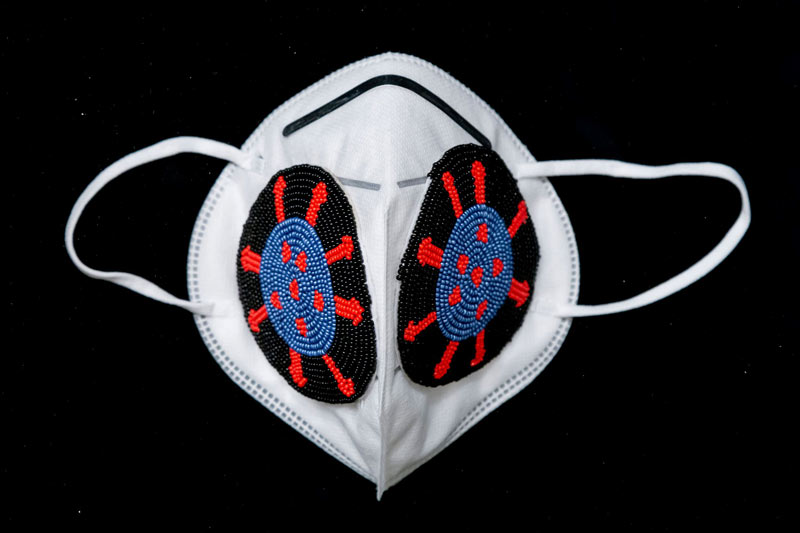

Cuthand, one of Saskatchewan’s leading artists, is well known for creating intricate beaded images of diseases—such as smallpox, cholera and tuberculosis—that reference colonization and trading, and their impacts on Indigenous people. She uses her work to explore social, environmental and historical issues, such as contaminated water and living conditions on First Nations, disease, colonialism and relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

Born in 1954 in Prince Albert, Sask., Cuthand decided to become an artist at the age of eight when she met artist Gerald Tailfeathers. Her first art materials included the 18-inch squares of orange paper that were thrown out in the processing of the Polaroid chest X-rays that students received during routine tuberculosis screenings.

Over the years since, Cuthand has built up a large body of work in a wide variety of media, including drawing, painting, photography, sculpture and video. In 2013, she was awarded a Saskatchewan Lieutenant Governor’s Arts Award and, in 2016, she was recognized as one of the College of Arts and Science’s Alumni of Influence. In 2020, she was named one of the winners of the prestigious Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts. Earlier this year, she was named a 2021 Alumni Achievement Award winner at USask.

Gay, a sessional lecturer in the Department of Art and Art History in USask’s College of Arts and Science, is currently pursuing a PhD at the University of Regina and is the first Curatorial Mitacs Fellow at the Mackenzie Art Gallery. In 2018, she received the Saskatchewan Arts Award for leadership for her work with curation and advocacy for creating space with Indigenous art and artists. In 2020, she served as a guest curator for borderLINE: 2020 Biennial of Contemporary Art at Remai Modern in Saskatoon.

As curator of Cuthand’s latest exhibition, Beads in the blood, Gay drew inspiration for the show’s name from her and Cuthand’s shared cultural heritage.

“Both Ruth and I are Cree and Scottish from different territories in Saskatchewan. We share an understanding that originates from our Cree worldview. In our language, words are contextualized as animate and inanimate beings, which points to our embodied understanding of who we are in relation with. Beads are animate in our language, meaning they are alive,” said Gay.

“Ruth’s work is speaking to colonialism and its effects on the Indigenous bodies, which can take the form of trauma and mental illness or introduced virus and disease through contact. The bead is the medium in which she signifies these concepts; whether it is trauma or otherwise, it physically resides in our blood. The bead is alive and is storied.”

Prior to Beads in the blood, Cuthand and Gay worked together on an artistic venture at Wanuskewin Heritage Park. They also collaborated when Gay was artistic director of The Red Shift Gallery, a small Indigenous-led artist-run centre in Saskatoon. Gay curated Dis-Ease, which was the first showing of Cuthand’s Trading series in 2010 and her first solo exhibition since 1999.

Gay described Cuthand as “an important figure in the development of Indigenous art discourse and history in Saskatchewan.”

Cuthand, who lives in Saskatoon, has inspired many students and future artists at USask, where she recently served as Indigenous artist-in-residence through a new program of the University Art Galleries and Collection. While in residency on campus, she introduced students, alumni, faculty, staff and others to beading through informal drop-in lessons in various USask locations, including the Gordon Oakes Red Bear Student Centre, the Arts Building and the Health Sciences Building.

Currently, buildings on the USask campus, including the art galleries, are closed to the public due to the COVID-19 pandemic, so Cuthand has not been connecting with students in person since the onset of the health crisis. However, she continues to interact with them online, such as through the virtual beading event Beadin’ 2021, which was held during Indigenous Achievement Week in February. She said she likes to have a presence at USask, her alma mater, where the number of Indigenous students continues to grow.

“I can kind of understand what they’re going through, you know? And I love doing beading with people, or even just chatting with them,” Cuthand said.

In the interview, Cuthand noted that she has been very busy since the COVID-19 pandemic began, and she has been repeatedly beading the coronavirus.

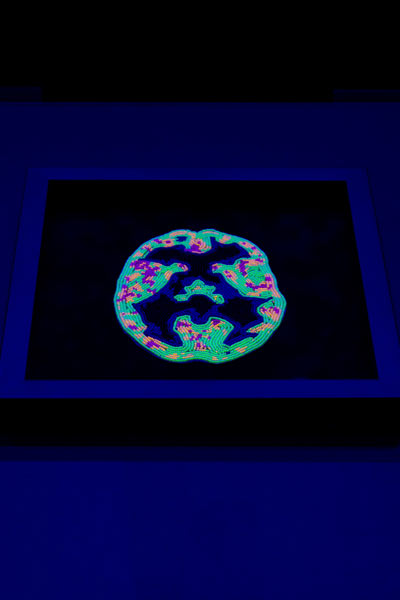

Some of Cuthand’s other new work is focused on brain scans, stemming from her interest in talking about mental health. Her artwork portrays a physical representation of what occurs in the brain when people are living with mental illness, using glow-in-the-dark beads that shine in neon colours under black light.

“To me, that’s a real highlight of my work,” she said.

Five brain scans were showcased in a room with black light in the USask gallery, enabling viewers to see which parts of the brain are animated when dealing with conditions such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“Ruth mentioned to me that most Indigenous folks suffer from PTSD because of the intergenerational effects of colonialism,” said Gay, noting that she “sought to utilize Cree story and narratives” in collaborating with Cuthand on the exhibition.

“The stories Ruth and I shared with one another are in the show for people to experience,” she said. “In my work I am seeking ways in which to do my work that validates and expresses the Swampy Cree ways of knowing within institutional settings like the gallery space. Ruth is an artist I trust and admire as a mentor. In my opinion, her work will be talked about for generations because of her critique and counter-narrative to colonial metanarratives and her generosity and support to her community.”