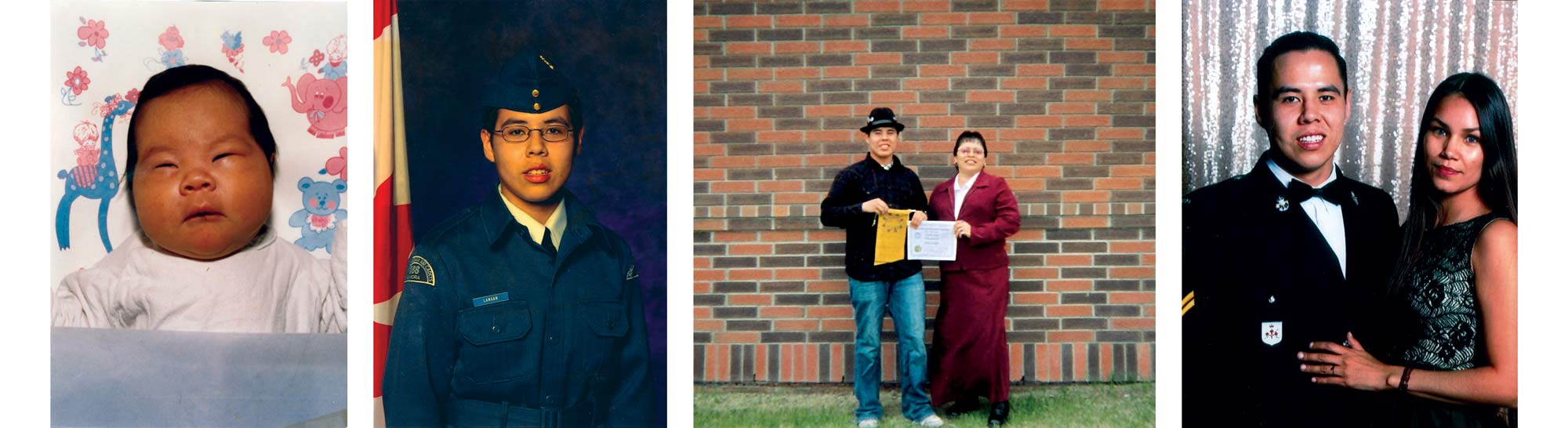

JOHN LANGAN REMEMBERS the day he cut his braids.

The morning of his Grade 1 school photos, Langan’s mother spent extra time fixing his long hair into a pair of perfect braids. When he sat in front of the camera, he was scolded by the photographer for his appearance and told to tuck his hair behind his head.

Langan’s mother stormed into the school to complain when she learned what happened, but to the six-year-old it only seemed to be another time he had caused trouble by being different.

“In my mind, I was just wanting to be a normal kid,” Langan says.

He found a pair of scissors, snipped off his braids and brought them to his mother. He remembers her tears.

“Why did you do this, my son?” she asked.

It’s not a happy memory for Langan, who grew up exposed to racism, crime, violence and drug use. But today, as a constable in the Saskatoon Police Service, the 30-year-old member of Keeseekoose First Nation no longer hides the uncomfortable parts of his past.

“It’s a lot to talk about. But it’s the reason why I’m here today,” he says. “It made me into a better police officer.”

Born in Regina, Sask., in 1988, Langan moved between more than a dozen different schools before his family settled in Canora, Sask., during his adolescence.

He remembers walking into his first day of school in Canora alongside his older brothers, some of the only Indigenous students in the school. A group of twelfth graders gave a mock war cry and sang “Ten Little Indians” as they walked past. Langan was in Grade 9.

“I was like, damn, this is going to be rough,” he recalls.

Eager to prove he was like everyone else, Langan made friends with a group of his non-Indigenous peers. Almost no one at school knew that his home life was unravelling.

Langan’s father died when Langan was a young child, and Langan and his brothers were raised by their mother and stepfather: a logger, welder and social worker who passed along his values and traditional cultural knowledge to Langan.

“He really instilled his work ethic into me—up until I was about 14,” says Langan.

Langan’s stepfather never spoke of it to his son when he was alive, but he had endured terrible abuse as a child at a residential school. By the time Langan was a teenager, his stepfather was turning to substance abuse to try to cope with his past. It started with alcohol, then pills, then “harder stuff,” Langan says.

Langan’s older brothers had left home by this time, and some were becoming involved in drugs and crime. With no strong role models left for him, he started getting into trouble.

When he was 14, he watched from an alley as his friends broke into a neighbourhood home and stole armfuls of video games. Soon after, a police officer was knocking at his door.

At the police station, Langan explained what happened: he didn’t participate in the crime and didn’t accept any stolen goods—but did nothing to stop his friends, either. The police believed him.

“Just to let you know, John,” he remembers the officer telling him, “your three friends tried to put it all on you.”

It was a turning point.

“I was like, ‘OK, I’ve got to start making some good choices here,’ ” says Langan. “I told myself I would be my own role model. Because I knew in the future that I was going to have kids. Because I knew I always wanted to be a dad.”

Langan received a reduced charge and was placed in an alternative measures program.

![[icon image] David Stobbe](images/langan_2.jpg)

He found a new circle of friends, joined the Royal Canadian Air Cadets and became president of his school’s Students Against Drunk Driving chapter. He found a spiritual mentor and made his culture a larger part of his life. He started to consider the idea of becoming a police officer.

Still, few people at school knew the real John Langan. Determined to fit in, to defy the stereotypes, he never spoke about the situation at home.

“I had an image to uphold,” says Langan. “I didn’t want people to know what my family was going through. I’d go to school, I’d put this face on like everything was OK, but what people didn’t know was my home life was just messed.”

By Grade 12, it was becoming unbearable.

“I would go to school and I wouldn’t have laces on my shoes because people were using them to tie their arms off,” says Langan. “I would walk into bathrooms and people were there with needles in their arms and dazed out.

“I was just like, man, I’ve got to get out of here.”

Langan packed a car with a few possessions and moved to Regina with one of his close friends. He finished high school in Prince Albert, Sask., and joined the Canadian Army Reserve.

He met Bianca Ermine, his future wife, at a powwow in 2008. Langan enrolled in the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Arts and Science and together they moved to Saskatoon in 2009.

Langan knew university was important for his future, but he had no clear path in mind. Remembering his high school interest in criminal justice, he eventually settled on the Aboriginal Justice and Criminology program in the Department of Sociology.

![Retired Sgt. Joel Pedersen (right) presented John Langan with his Saskatoon Police Service badge in 2017. [icon image] Bianca Ermine](images/langan_badge.jpg)

Langan had good relationships with his professors, especially Dr. Carolyn Brooks (BA’88, MA’93, PhD’09).

“She was always there to support me and point me in the right direction,” he says.

Brooks saw something in Langan.

“She would say, ‘I think police would be the best for you,’ but in the back of my mind I would be like, ‘I can’t become one,’ ” recalls Langan.

Still trying to “look and be like everybody else,” he didn’t voice his doubts, but Langan knew police services were rigorous in their background checks. He had pleaded guilty to a criminal charge as a youth. His brothers had been involved in stabbings and bank robberies and had seen the inside of “every single jail” in the province.

Langan completed his Bachelor of Arts in 2013. Instead of applying to the police service, he worked at the Saskatoon Open Door Society and took contracts with the Canadian Armed Forces for the next several years.

Meanwhile, Langan’s stepfather passed away. Langan’s spirituality was by now a central part of his life, and under the guidance of a traditional knowledge keeper, he was learning to help run cultural ceremonies.

At a night lodge ceremony, he asked the spirits if he should become a police officer and was given encouragement. He decided it was time.

“I didn’t want to say, ‘What if?’ ” Langan says.

In his application to the Saskatoon police, he laid it all out: His brush with the law at 14. His brothers’ gang connections. Crimes he had witnessed. Times he’d sped on the highway.

“I put in everything—everything,” he says. “It was really, really scary.”

He was invited for an interview, then for a standard polygraph test. For hours, attached to a machine in a room with a police officer, he spoke openly of the things he had kept secret most of his life.

“I maintained eye contact the whole time. I said, ‘This is me. This is everything about me. Honestly, I have nothing to hide.’ ”

From a long list of applicants, Langan was hired. He was sent to the Saskatchewan Police College and sworn in as a Saskatoon police officer in 2017.

Langan turned out to be exactly the kind of officer the police service wanted.

“He’s got a strong military background. He’s in great physical condition. He’s intelligent. He’s a U of S grad,” says Troy Cooper, chief of the Saskatoon Police Service, who has come to know Langan personally.

“He’s one of those guys that’s sort of the salt of the Earth. He’s the person that people around him rely on to make sure things get done.”

![John Langan was the keynote speaker at the Saskatoon Police Service’s annual diversity breakfast on March 21, 2019. [icon image] Saskatoon Police Service](images/langan_speaker.jpg)

When Langan thinks about his work as a police constable, he remembers another lesson his stepfather left him: “You have to live it to understand it.”

Langan has lived it. His experiences as a youth give him a rare perspective on the scenes of crime and addiction he sees on the job. When he tells young people caught in the justice system that they can turn their lives around, he is the proof.

“It’s about the decisions you make growing up and not using your upbringing as an excuse, but using it as power,” Langan says.

Just as important is his connection to his culture, which has proven invaluable for an officer serving in a city with a large Indigenous population.

“When I go into these homes of people who are Indigenous, right away I have that credibility,” Langan says. “Even with young people, I’ll speak Cree, the small amount that I do know. Right away, they’ll start to listen.”

Langan has recently started giving presentations to his fellow officers and to the public about his culture and upbringing. He has taken Cooper with him to participate in ceremonies.

“(Langan) is proud of his history and his culture, and that’s helped us a lot,” says Cooper. “Most importantly, he’s willing to share his understanding and his knowledge of that culture.”

There are signs that the society he grew up in is changing, Langan says.

“I think it’s starting to shift now, where people are more curious about what Indigenous people believe. But now you have gaps of people who really don’t know who they are yet. And that’s what you see on the streets, is people who don’t know who they are, and they’re trying to find out.”

Langan married Ermine, a social worker, in a traditional Cree ceremony in 2017. When he speaks of the many friends and guides—family members, spiritual advisers, teachers, army officers—who helped him along his path, his wife stands out.

“She is everything to me. Behind every strong man there is a strong woman, and she is strong,” Langan says.

Along with his police career, Langan is a master corporal in the army reserve and is being mentored as a traditional knowledge keeper. At age 30, he is adjusting to being seen in a new way: as a role model.

Joel Pedersen, a retired police detective sergeant and a chief warrant officer in Langan’s army unit, is one of the people Langan says he looks up to most. Pedersen calls Langan “wise beyond his years.”

“John is inspiring for many people. He’s an inspiration,” Pedersen says.

It has been hard to accept being viewed as a role model to his peers and community, Langan admits. It’s a job he feels more comfortable with at home.

Langan and Ermine have two children and are fostering a third. Their son wears his hair in braids.

“I tell him, ‘This is who we are,’ ” says Langan.