A bright light on the past

Chemistry meets culture in a new course that gets students hands-on with ancient artifacts at the Canadian Light Source

By Colleen MacPherson

A chemistry student and an archaeology student walked into a synchrotron facility last fall, and discovered a world of possibilities by combining science and the humanities.

In a unique course offered at the College of Arts & Science in the fall term, students studying chemistry teamed up with their counterparts in Classical, Medieval and Renaissance Studies. They used the power of the Canadian Light Source (CLS) to explore material culture, the chemical and material composition of ancient glass, pottery and coins. The students used the results of their research to consider the study and preservation of the objects, and to expand understanding of the cultures that produced them.

For archaeology student Michael Lewis, the course was a chance to extend his learning.

“To do original, interdisciplinary research is a very unique opportunity,” he said. “Archaeology is a very interdisciplinary area of study. For example, analytical chemistry is a sub-discipline of archaeology and in many classes, we talk about the science but you don’t get to experience it as an undergraduate.”

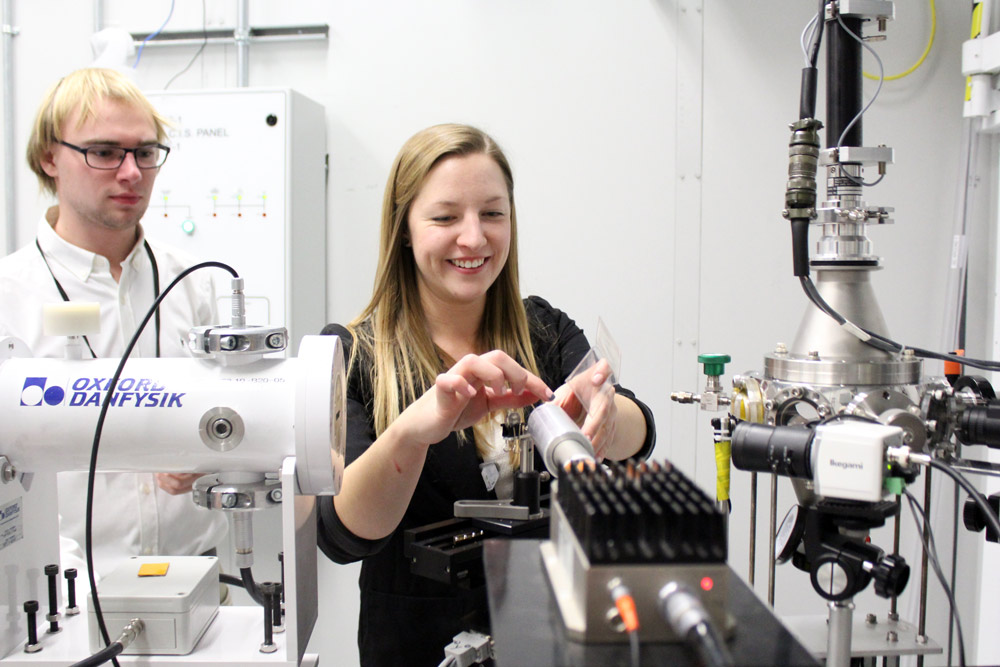

Chemistry student Melissa Shaw took the course—called CHEM/CMRS 398.3: Using Big Science for the Study of Material Culture—not only for a guaranteed synchrotron experience but also for the opportunity “to bridge my own learning gap between history classes I’ve taken and chemistry classes. A course like this really gives you an appreciation of what’s out there in terms of disciplines.”

The 14 students in the course worked in small groups on three different projects based on their interests. Both Lewis and Shaw commented on how much support the students gave each other as they moved into unfamiliar territory outside their disciplines. “There was more collaboration than I expected,” said Shaw, adding that without the peer teaching “I think I’d be just poking around with a stick in the dark.”

Tracene Harvey, director of the university’s Museum of Antiquities and one of the course developers, said the work was challenging for all of the students, pushing them “a little bit out of their comfort zones.” But sharing their diverse perspectives “helped them understand the significance of data in the larger picture. It’s an arts and science course in the truest sense.”

“We really wanted to offer students something they hadn’t had before—students from very different disciplines coming together in an authentic research experience,” said Professor Thomas Ellis from the Department of Chemistry, who contributed to the course development along with Harvey and Tracy Walker, education program lead at the CLS. “The benefit for students is that they can take what they’ve learned so far and apply it, but apply it to something really fun and interesting.”

Using Big Science for the Study of Material Culture is a model for what is possible, he said. The developers will write up and, they hope, publish about the experience, and plan to present at chemistry, education and antiquities conferences in the hope of inspiring others. Ellis, for one, believes the possibilities are limitless. “This kind of class could be done with all kinds of fascinating combinations of disciplines.”

Culture in objects

The 14 students who took CHEM/CMRS 398.3: Using Big Science for the Study of Material Culture tackled three projects that required synchrotron spectroscopy. This is a summary of their work.

How pure is pure?

Coins in ancient Greece are believed to have followed a strict standard of purity based on weight and elemental composition while Roman currency is understood to show changes in composition over time due mainly to debasement—mixing silver with non-precious metals like copper and lead.

Using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis, the students investigated the deep layers of coins to determine the purity of silver in Athenian coins compared to the silver coinage of nearby Greek cities, and potentially shed light on the concept of wealth and commerce in Ancient Greece and Rome.

Digging into the dirt

Pottery artifacts often remain buried in the ground for hundreds or thousands of years but does their analysis take into account potential sediment contamination? And does the way pottery is made play a role in the level of contamination?

This project involved the use of X-ray fluorescence (XRF), X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and powder X-ray diffraction (pXRD) to determine to how deep into the pottery soil contamination has occurred and how manufacturing methods affect contamination levels. The results might lead to non-destructive methods of contamination removal.

Drawing a bead on beads

Faience is an ancient glass-like substance that corrodes and breaks down over time. It has been subject to little research. Without proper knowledge and understanding, faience artifacts are at risk of degradation, limiting their lifespan and availability for future generations to appreciate and study.

Using X-ray, infrared (IR), and XANES, the students analyzed the chemical compositions of the various materials of faience beads. The goal was to determine the differences between modern and ancient counterparts of faience, and to isolate potential causes of degradation in the material.

Colleen MacPherson is a Saskatoon-based freelance writer.