The chemistry of That Ngo

The world-renowned chemist arrived in Saskatchewan in 1966 with $50 he'd smuggled in his tie ... and not much else

By Trevor Pritchard (BA'01)

It was 1966, and That Ngo (BSc’69, SC’70, PhD’74) was on a plane to Saskatchewan with 50 dollars smuggled in his tie—and not much else.

“It was a huge decision,” recalls Ngo, now 71 and retired in Irvine, California after an accolade-filled career as a University of Saskatchewan-trained biochemist. “I didn’t have much of a chance to [go to university] in Indonesia.”

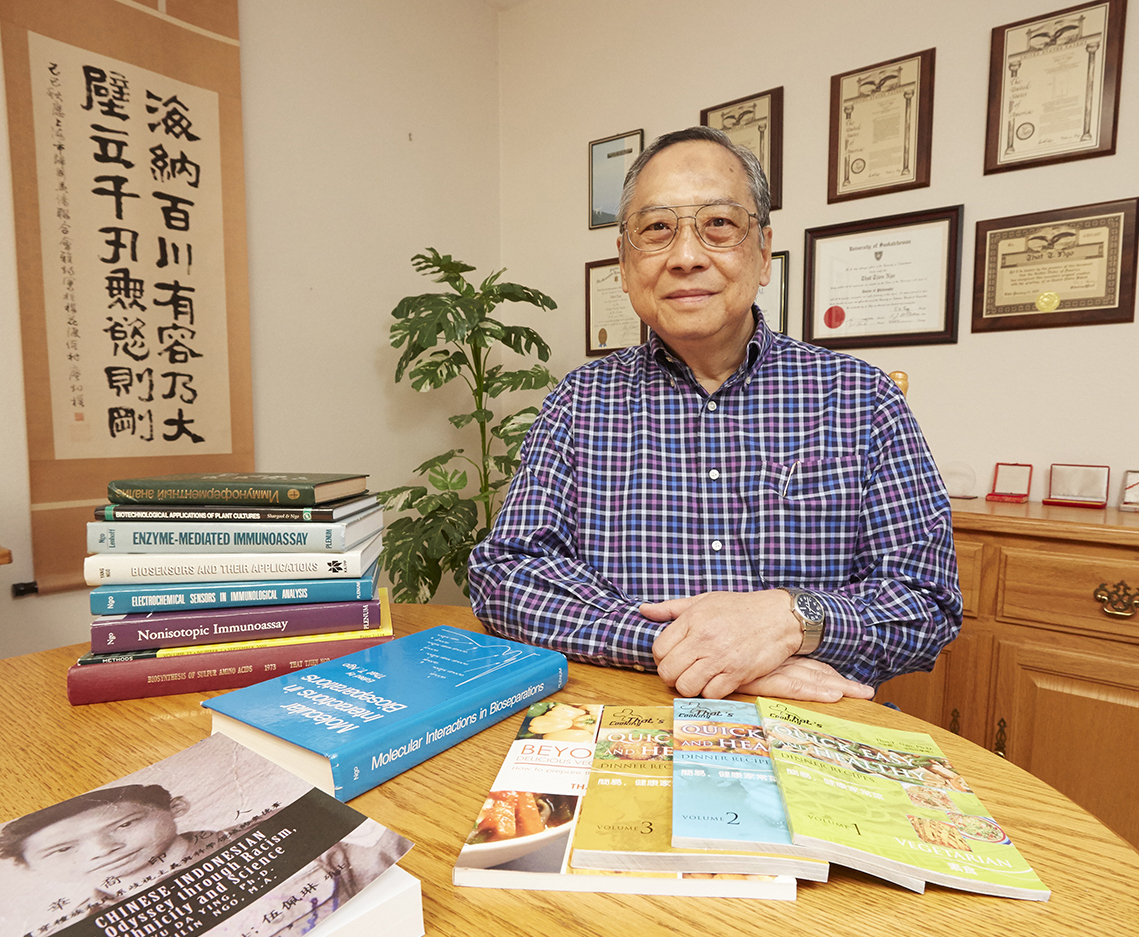

Ngo may no longer be toiling away in the lab every day, but he’s arguably working as hard as ever. It’s just that his current work has a more literary focus. Since retiring, he’s written poetry, newspaper articles, four cookbooks, and the memoir Chinese-Indonesian: An Odyssey through Racism, Ethnicity and Science. It’s a highly personal look at the prejudice and hardships that Chinese immigrants to Indonesia faced in the 1960s under the Sukarno and Suharto regimes.

Published in 2013 and currently being translated into Indonesian, Chinese-Indonesian is a detailed exploration of Ngo’s life as a young man in his family’s adopted homeland, from his time in a Chinese private school to his eventual decision to leave Indonesia behind and move to Canada to study.

In one chapter he describes being spit upon by a member of an Indonesian student militia simply for being a “cino,” a racial slur commonly directed towards Chinese-Indonesians. Later, he writes about being “spared the agony” of having to change his name to something less Chinese-sounding—a policy instituted by the Suharto government after he left.

“I wanted [my daughter] to know how I came about, how my parents and my grandparents came from China to Indonesia, what I went through,” says Ngo, explaining why he wrote the memoir. “It’s become a family history.”

Ngo’s family were Chinese immigrants. He was born in a small Indonesian town in East Java at the foot of an active volcano. But because of his parents’ immigrant status, and the fact that Ngo wasn’t old enough to apply for Indonesian citizenship, he was barred from state-run schools and attended a private Chinese-language institution instead. When he graduated, the Indonesian government refused to recognize his diploma, leaving him few opportunities for post-secondary study in the country.

Ngo did have an uncle who’d moved to Saskatoon a few years earlier, however: a doctor who cared for tuberculosis patients at the city’s former sanatorium. And he was more than willing to help with his nephew’s transition.

It was midway through the first semester when, in October 1966, Ngo arrived at the U of S. His English was poor, and he could barely understand what his professors were saying. On his first chemistry midterm, Ngo barely got 20 per cent, and his next exam didn’t go much better.

But Ngo knew it was the language barrier that was his impediment, not the equations and formulas. Nights of hard work paid off; Ngo would ace his third exam with a perfect score, and in 1970 he received his degree, with honours. Three years later he would leave the U of S with his biochemistry PhD securely in hand.

“The people in Saskatoon were tremendous,” says Ngo, who supported himself by working at the university’s library after the newly installed Suharto government confiscated his family’s business back in Indonesia. “I can’t thank them enough.”

After graduating, Ngo would go on to a lengthy career as a biochemist, first in academia and later as the president and CEO of multiple private firms, both in Canada and the United States. He has published more than 140 articles and is the holder of 14 different patents, although not for perhaps his most significant accomplishment: being the co-discoverer of a procedure called the Ngo-Lenhoff assay, which eventually allowed for the development of OneTouch home blood glucose tests for diabetes patients. (As Ngo says, he and his colleague were “old school,” too focused on the research to realize its monetary value.)

Now, Ngo hopes the translation of his memoir into Indonesian will be completed in the coming months.

He says he won’t be surprised if the book gets a “mixed reaction” among Indonesian readers, but he’s not shying away from some of the difficult truths.

“Some Chinese-Indonesians didn’t like the memoir. Some [native] Indonesians may not like it either,” admits Ngo. “But whatever I’ve said in there, it’s completely true.”

Of course, not all of Ngo’s written exploits handle such sensitive subject matter. He’s also written those aforementioned cookbooks—one of which is available on Amazon, Ngo notes—that feature recipes he’s perfected over the years.

“I’m an experimental biochemist … so I use my kitchen as the lab,” says Ngo. “And my wife and daughter, they are the guinea pigs.”

One of his favourite, family-approved dishes is gado gado, an Indonesian salad that features boiled vegetables, sliced eggs and peanut sauce. It might seem like a curious choice, given his fraught relationship with his homeland, but Ngo—who still has a brother and sister living in Indonesia—says it’s not the people or culture of Indonesia that trouble him.

Rather, it’s the long line of corrupt officials who’ve regarded the country as “their own personal fief.”

“I still have a strong tie to Indonesia. I love Indonesian food,” says Ngo. “I hope the newly-elected president, Joko Widodo, can clean up the government and not cave in to special interest groups.”

This article appeared in the Spring 2015 issue of the Arts & Science magazine