USask archaeology students’ hands-on forensic experience in local cemetery could support TRC Calls to Action

The training the students received at the Nutana Pioneer Cemetery in Saskatoon could prove valuable as searches continue across Canada for the remains of Indigenous children who died while attending residential schools

By Shannon Boklaschuk

For several days this week, a small group of University of Saskatchewan (USask) archaeology students used various methods and technologies—such as ground-penetrating radar (GPR)—to search for lost graves at a local cemetery.

The hands-on training the students received at the Nutana Pioneer Cemetery in Saskatoon could prove valuable as searches continue across Canada for the remains of Indigenous children who died while attending residential schools, said Dr. Terence Clark (PhD), a faculty member in the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology in USask’s College of Arts and Science.

Clark has collaborated with students and other archaeologists to locate unmarked burial locations at sites of now-shuttered residential schools in Canada. For the past couple of years, he has also worked with the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR), which was created as part of the mandate of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), to develop a plan for locating the remains of missing children at residential school sites across the country.

“We really want to know where all of those children are to remember them, but to also protect their graves from any future disturbance,” Clark said.

On April 6, 2021, Clark first took a group of nine undergraduate students from his ARCH 385 class, as well as two graduate students, to the Nutana Cemetery. The team used GPR as they attempted to map the known and unknown graves in the cemetery, located near the intersection of St. Henry Avenue and Ruth Street West in Saskatoon, that were lost due to incomplete records from the late 19th century and early 20th century.

“What the GPR does is identify where the graves are most likely to be but, without digging, you’re not 100-per-cent certain,” he said. “That’s why we’re trying to use multiple technologies to be as certain as humanly possible without digging.”

Clark noted that in the 1930s, due to erosion along the riverbank, some graves in the cemetery were moved. While some of the human remains were transferred to Saskatoon’s Woodlawn Cemetery, some were thought to be relocated to unknown locations in other parts of Nutana Cemetery, he said. Clark and his students went to the cemetery to find the unknown graves as well as to help the City of Saskatoon determine which other graves could be impacted by future erosion.

According to the City of Saskatoon, there are 162 known burials at Nutana Cemetery, of which only 144 graves are identified. Of these, 51 are babies; 14 more are children under the age of 16.

“You’re always kind of taken aback at the number of children that are here, so it always makes me think about vaccination and what happened before vaccination,” Clark said. “There’s gravestones with five or six children written on them, as people just keep losing them, and it’s four months and two months and a year (old). Life was just so much harder back then, I think.”

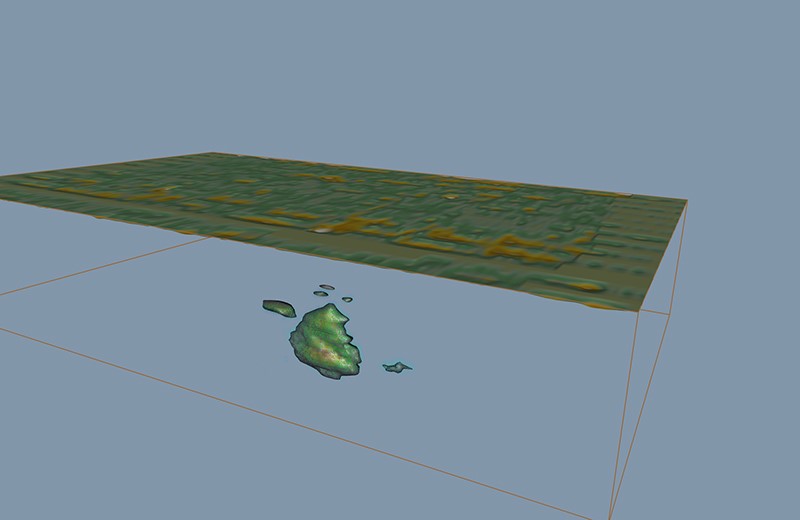

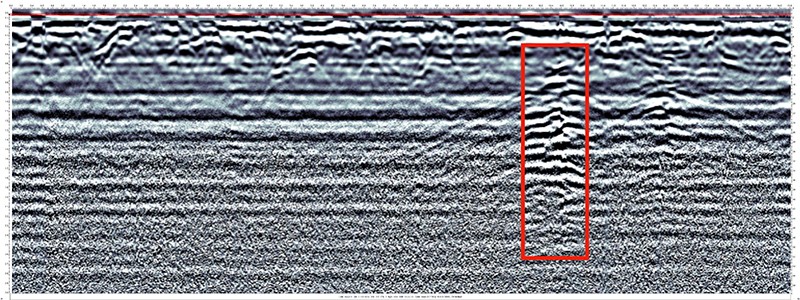

The GPR survey Clark and his students conducted involved pulling a radar unit along the ground surface of the cemetery in a grid pattern. The GPR machine transmitted radar waves into the soil and then measured the time it took for the waves to return in nanoseconds, since differences in time can be caused by factors such as buried rocks, changes in stratigraphy and grave shafts. While the machine cannot find a burial per se, it can locate any areas consistent with a grave shaft or coffin remnants that may still be present, said Clark, who noted GPR is the standard tool for finding graves in forensics.

The techniques Clark and his students used were selected so that they would not disturb the gravesites nor cause any damage to the cemetery, he said. This also included total station mapping of the site using a laser total station—the same as that employed by construction survey crews—to provide an accurate map of all the visible features, as well as the topography of the cemetery.

“The City is happy to help the University of Saskatchewan test important research tools,” said City archivist Jeff O’Brien. “Not only are we hoping to achieve a better record of lost graves, but the application of this work further allows the City to support the TRC’s Calls to Action.”

Clark said his students appreciated the experiential learning opportunity, especially during a pandemic year when many USask classes have been taught remotely to protect the health and safety of faculty, staff, and students.

“This is really applicable for archaeology elsewhere in the country or around the world. I think they’re learning some valuable skills out here,” Clark said. “All of my grad students need to know how to do it. I feel like by training undergrads I’m preparing them for grad school or jobs in archaeology, so I think it’s absolutely vital.”

Archaeology student Lennon Sproule said it was exciting to get hands-on experience with ground-penetrating radar and total station mapping, noting the “technology is fairly easy to use in the field after a short amount of training.”

“The experience gained from the field work will give me the tools to hopefully be more attractive to potential employers. Additionally, the skills gained will help me work more efficiently, and less invasively, while still acquiring important archaeological data,” Sproule said.

Archaeology student Micaela Champagne, who was honoured with a USask Indigenous Student Achievement Award earlier this year, was also at the Nutana Cemetery this week. She said that as an Indigenous person and as someone who studies archaeology, she walks “between two worlds of research and cultural preservation.”

“It is extremely important to acknowledge the non-ethical treatment of Indigenous people in archaeology in the past. By doing so, we can move forward to a future that is based on mutual respect and understanding,” said Champagne.

“The non-invasive methods that we are employing at Nutana Cemetery can be applied to how we do Indigenous archaeology in Canada, especially in the case of locating unmarked graves at residential schools. I think it is important, especially in the case of human remains, that they are treated with respect and dignity. By using these non-invasive procedures, we can provide closure and give communities the knowledge so they can make informed decisions about leaving the graves or reinterring them in other locations.”

Dr. Kisha Supernant (PhD), an archaeologist currently serving as the acting president of the Indigenous Heritage Circle, said ground-penetrating radar and other remote-sensing technologies can support a direct response to the TRC Calls to Action 73-76, which call for locating the missing children and supporting communities in commemorating the burial locations of these children when they are located. Supernant and Clark have previously worked together, along with the NCTR and the Muskowekwan First Nation, on using ground-penetrating radar to locate possible burial locations around the Muskowekwan residential school.

“The work at Nutana (Cemetery) is a great example of combining multiple types of remote sensing in areas where we know there are burials present,” said Supernant. “The information from this survey will help refine our techniques for use around residential school sites.”

As an Indigenous archaeologist, Supernant said she believes archaeology has an important role to play in supporting Indigenous communities to locate unmarked graves.

“Archaeology does not have a great history of working with Indigenous communities, but that has been changing over the past few decades,” she said. “Using the tools of archaeology to address community needs and respond to the TRC Calls to Action is an important step forward in building better relationships between archaeologists and Indigenous communities.”

(with files from the City of Saskatoon)