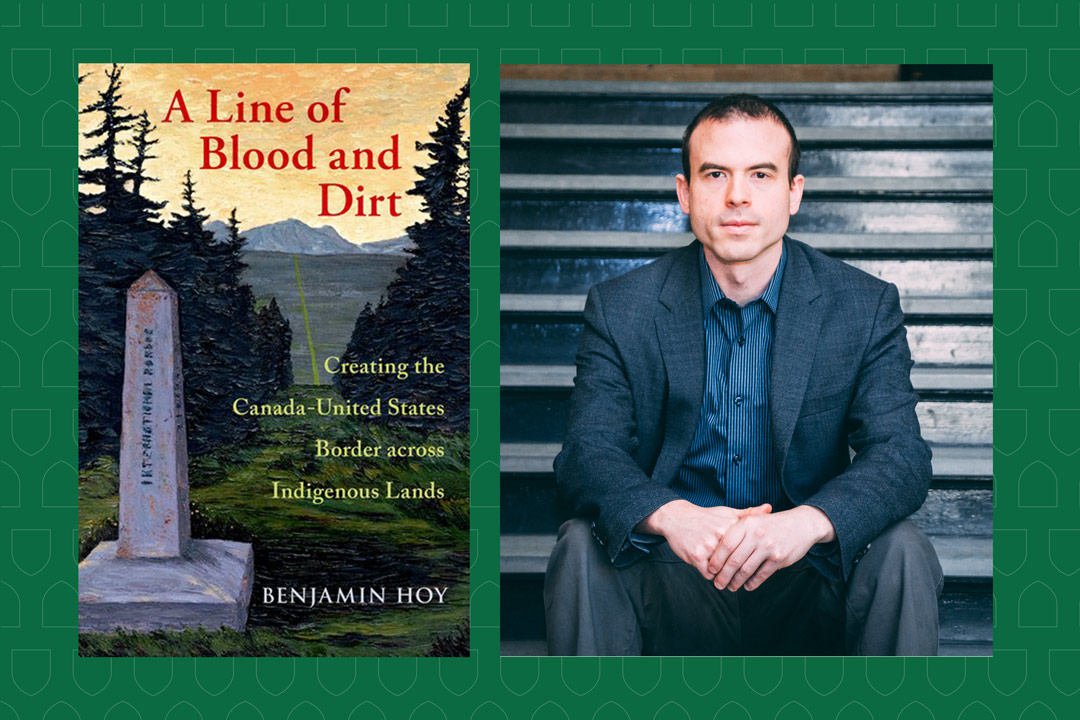

New book by USask historian shows Canada-U.S. border in new light

A Line of Blood and Dirt: Creating the Canada-United States Border across Indigenous Lands by Dr. Benjamin Hoy (PhD) launches this month

By Chris Putnam

A new book by a University of Saskatchewan (USask) historian is an ambitious exploration of the messy and often violent history of the world’s longest undefended border.

A Line of Blood and Dirt: Creating the Canada-United States Border across Indigenous Lands by Dr. Benjamin Hoy (PhD) launches this month from Oxford University Press. The book covers 150 years of history spanning two countries and dozens of ethnic groups.

“Like many, I had always thought of the Canada-U.S. border as a peaceful place that mostly affected those who lived directly in its shadow. As I began to look more closely, I began to uncover the enormous violence that goes into creating and maintaining a border,” said Hoy, an assistant professor in the College of Arts and Science’s Department of History.

A Line of Blood and Dirt considers the impact of events such as the American Revolution, the War of 1812, the Red River Resistance and the Cypress Hills Massacre on the creation and operation of the border—what Hoy calls “a border born in blood.”

“From the very outset, Canada and the United States believed that building a national border on Indigenous lands required erasing pre-existing territorial boundaries, leading to tremendous suffering and deprivation.”

The product of 12 years of research and writing, Hoy’s debut book draws on diaries, deportation records, federal correspondence and nearly 800 oral histories from Canada and the United States.

Hoy argues that the border was never very effective at physically stopping people from crossing, but that governments found other ways to exert control.

In the aftermath of the 1862 Dakota War, for example, hundreds of the defeated Dakota escaped from the United States into Canada. The American military responded by hiring men to kidnap prominent Dakota so they could stand trial in the United States.

The United States government even arranged to dig up the graves of combatants who had moved to Canada and shipped their remains to New York for display in a museum.

“While the U.S. government had failed to stop the Dakota from crossing the Canada-U.S. border, it had found ways to project fear across the line, impacting how people lived their lives decades after the war itself had ended,” said Hoy.

Personal histories in the book are complemented by the use of cutting-edge historical geographic information system (HGIS) methods.

Using HGIS software, Hoy digitally mapped the locations of tens of thousands of border administrators over a period of 50 years. As a result, the book “is able to track what the border looked like in practice, in ways not possible a decade ago,” said Hoy, who directs the HGIS Lab in the College of Arts and Science.

A dual Canada-U.S. citizen, Hoy has been fascinated by the border ever since he got a summer job as a student digitizing 19th-century Canadian censuses.

“As part of that job, I started to do research on how the census could be used to help track how Indigenous people moved across the international line. I fell in love with that work. It was an opportunity to see patterns otherwise invisible in the historic record and helped me understand why the world I grew up in and traversed looked the way it did,” said Hoy.