New book explores queer history on the Prairies

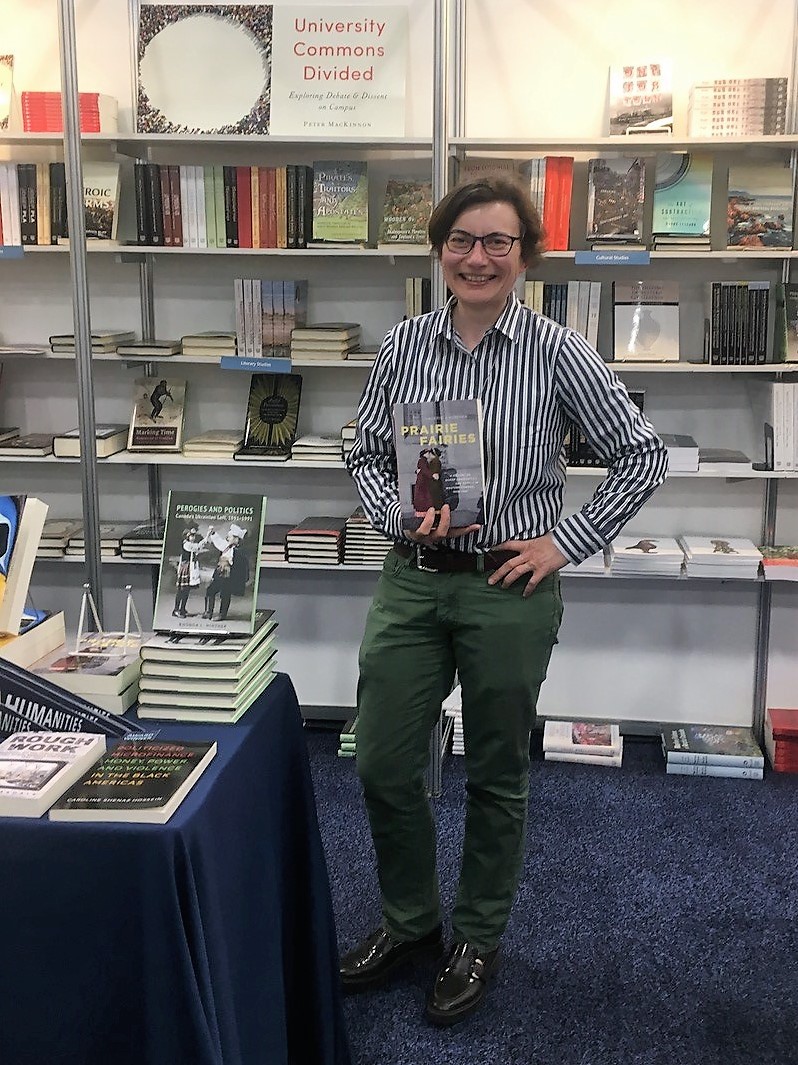

A Department of History professor utilized archival material at the university in writing Prairie Fairies

By Shannon Boklaschuk

The origins of a University of Saskatchewan professor’s new book can be traced back to a Post-it Note.

Valerie Korinek, a professor in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Science, has written Prairie Fairies: A History of Queer Communities and People in Western Canada, 1930-1985. The book draws on oral, archival and cultural histories to explore the experiences of queer urban and rural people on the Prairies, with a particular focus on the cities of Saskatoon, Regina, Winnipeg, Edmonton and Calgary.

Although the book has just been published, it got its start back in 1996, when Korinek first arrived at the U of S from the University of Toronto. It was then that she received a Post-it Note from one of her former colleagues in the history department, the now-retired professor Gary Hanson, which included two names and “the cryptic comment, ‘You should contact these people. You’d find them interesting,’ ” Korinek recalled.

Because Korinek was busy with her new academic post, it wasn’t until April 1997 that she called up U of S librarian Neil Richards, whose name was included on the note. Richards—an activist who posthumously received the Saskatchewan Order of Merit in April 2018—had made it his life’s work to preserve, gather and document the heritage of LGBTQ communities. Between 1985 and 2015, Richards entrusted his enormous collection of LGBTQ archives to the U of S library. It was one of the earliest and largest collections of LGBTQ interest to be acquired by a Canadian public archive.

“I met Neil and I was completely blown away by the stuff he had donated to the Saskatchewan Archives Board, to the University Archives. Ten minutes into that maybe hour-long conversation, it was readily apparent to me that nobody had used the materials and this was a huge gift that he had given the province and the university,” Korinek said.

“Basically, he had kept every single piece of paper about gay and lesbian organizing in the Western region since those groups started in the early ’70s, and he had cut out articles from the newspaper from the moment he arrived in the city (from Ontario). Neil had also gone and volunteered at the Lesbian and Gay Archives in Toronto and so, as part of that arrangement, he photocopied a lot of materials that they had and brought them back to Saskatoon.

“So, when I saw how much material was here, (I knew) what a great social and regional and urban history it would be of queer people in the Prairies. I didn’t have very much familiarity with the Prairies before I moved here, and had assumed, stereotypically like everyone does, if you grow up gay or lesbian in the Prairies—which was how people referred to themselves then; queer now—you would just move. You would move to Vancouver, you’d move to Toronto, you’d move to Montreal. So I gradually began to realize as I went about my weekly life well, no, people hadn’t moved, and here was all of this documentation.”

Around the same time that she met with Richards, Korinek had been working on her book Roughing it in the Suburbs: Reading Chatelaine Magazine in the Fifties and Sixties. She was interested in feminism, sexuality and gender in Canada after the Second World War and was already quite familiar with literature in the U.S. about gay urban space. After viewing Richards’ materials, Korinek saw an opportunity to write what she thought of, at the time, as “a little book” about queer people and queer communities on the Prairies.

Korinek got started on the book following a successful Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) grant application. After she visited LGBTQ archives throughout Western Canada, conducted interviews and spent more than a decade writing the book, the 528-page Prairie Fairies was published by University of Toronto Press.

“It became both an academic and personal labour of love to try and utilize Neil’s archives, the oral interviews I collected myself, the ones I found in Winnipeg and cultural documents to write this history,” she said.

The book’s cover features a 1914 archival photo of U of S alumna Annie Maude (Nan) McKay sharing an embrace and a kiss with a woman named Hope outside of a university residence building. In 1915, McKay—who was born in 1892 at Fort à la Corne, Sask.—became the first Métis and Indigenous woman to graduate from the U of S when she was awarded a Bachelor of Arts degree.

The book’s timeframe—1930-1985—encapsulates two parts of queer life on the Prairies. The 1930s through to 1969 is what Korinek describes as “pre-gay and lesbian community formation.” The 1970s, however, marked the beginning of what Korinek calls “gay and lesbian liberation,” which included the creation of gay and lesbian membership clubs, newsletters and magazines.

The 1980s brought a new challenge with the dawn of the AIDS epidemic. Korinek decided to end her book in 1985 as a result.

“I ended at ’85 not because political activity ends then, but that’s really the point at which most of these cities turn their resources—limited resources—towards AIDS awareness, AIDS education and AIDS activism and have to turn away from the community centres and the more general kind of membership clubs that they had run up until that point.”

Korinek said there’s several key messages in Prairie Fairies, and the first and most simple is that queer people have always lived on the Prairies—even if they haven’t always been welcomed or acknowledged by others. The new book is a “start at writing a history of a group that hasn’t had much historical attention,” she said.

Another facet of Prairie Fairies is that it looks at the ways in which Saskatoon, Regina, Winnipeg, Calgary and Edmonton were interconnected, but also at the ways in which they were similar and different. For example, Saskatoon was very political, Winnipeg was quite invested in education and media production and Edmonton specialized in counselling programs, Korinek said.

“This world is interconnected. So Prairie activists were participants in the national Canadian activist scene. They were travelling to the United States and, in some ways, Prairie activists were leaders in the ’70s and early ’80s—and that is something that is just absolutely not known,” she said.

“There were a series of conferences between 1971 and 1982 or ’83 and, of those 10 conferences, three of them were held in the Prairie region—in Winnipeg, in Saskatoon, in Calgary. That’s really important to know, that Prairie activists were leaders nationally.”

Korinek has reflected on some of the progress that has been made on the Prairies since 1985 and has not ruled out another book examining more recent LGBTQ history. In 2017, for example, the Saskatoon Pride Festival celebrated its 25th anniversary with a record-breaking parade. Korinek said advances have been made as people have gotten to know their LGBTQ counterparts.

“Once they see people living right next door, it makes it a little bit harder to hate and a little bit harder to just have a knee-jerk reaction to difference,” she said.

“And that’s really good—it’s one of the reasons why activists in the ’70s said, ‘Encourage people to come out. Encourage people to tell other people that they are gay and lesbian,’ because they knew that that would break down barriers. It would demystify our world.”