In 1933, the University of Saskatchewan was in crisis. A drastic move to cut costs began a chain of events no one could have predicted: a friendship that crossed an ocean, a family’s narrow escape from Nazi Germany and two Nobel Prizes in Chemistry.

Image sources: University of Saskatchewan Archives and Special Collections, Henry Taube fonds, Luise Herzberg fonds.

JOHN SPINKS MUST have known the news wasn’t good when he was called into the office of U of S President Walter Murray in the spring of 1933. In his three years since joining the Department of Chemistry, Spinks had seen the Great Depression devastate Saskatchewan’s economy and the university’s budget. Salaries had been slashed; the university had given serious thought to closing some smaller schools and colleges entirely.

Now, President Murray was asking Spinks and the other unmarried junior faculty members to take a year’s leave with only a “reasonably good” chance of returning to a job when it was over.

Spinks wrote a hopeful letter to a German physicist named Gerhard Herzberg, who, at the age of 29, was already known as a rising star in the emerging field of experimental spectroscopy. Herzberg responded by inviting Spinks to spend his unexpected year off working in Herzberg’s laboratory in Germany.

Spinks arrived in the city of Darmstadt a few months after Adolf Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor of Germany. The chemist spent a memorable year collaborating with Herzberg on research while renting a room in the same house as Herzberg and his wife, Luise, herself a gifted physicist. Spinks and the Herzbergs built a close friendship, taking in the culture and natural beauty of Darmstadt even as—Spinks later wrote—“there were Stormtroopers marching with a heavy tread through the cobbled streets.”

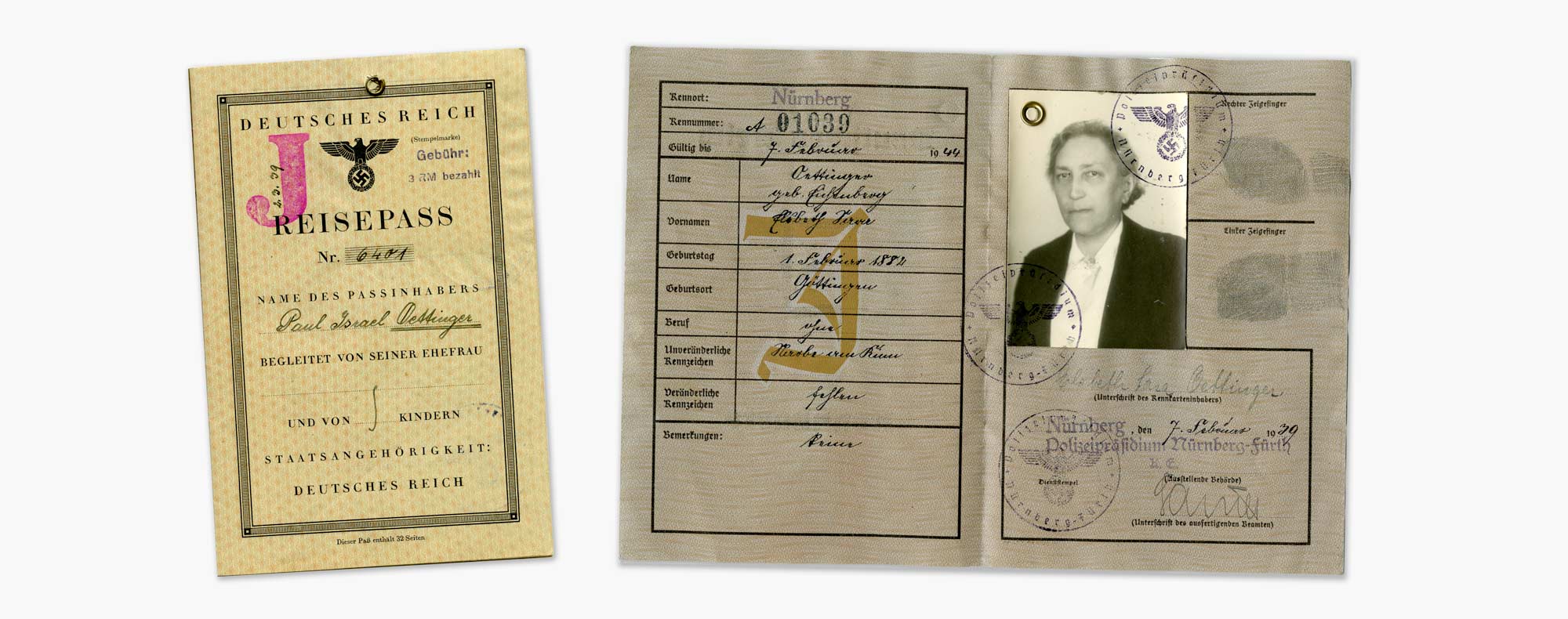

The Herzbergs’ situation grew precarious after Spinks returned to the U of S in 1934. Luise Herzberg was Jewish, and her husband’s colleagues had begun to notice that he did not participate in book-burning festivities or start his classes with a Heil Hitler salute. Late that year, he was stripped of his teaching duties and informed that his research position would shortly end.

The Herzbergs realized it was time to leave Germany, but they seemed to be too late. An earlier exodus of German scientists had filled the faculty openings at every university they contacted. Their last hope was a tenuous connection to a university they had never seen on the distant Canadian prairie.

The University of Saskatchewan was one of the most unlikely places in the world for a physicist such as Gerhard Herzberg to end up. The university performed no spectroscopic research, had none of the necessary equipment and was located far from North America’s major research centres. The bulk of the institution’s assets still “consisted of a bundle of IOUs in [Murray’s] safe,” according to Spinks.

But Spinks’ incessant praise for Herzberg convinced Murray to offer the German physicist a guest professorship, with help from a Carnegie Corporation grant to cover his starting salary. Despite some misgivings, the Herzbergs accepted. They left behind their home and their families with only $2.50 to each of their names—all they were permitted to take out of the country.

Saskatoon was a “pleasant surprise” for the Herzbergs, filled with friendly people, bright students and charming landscapes. What started as a temporary refuge stretched into a 10-year stay. Within a few years of his arrival, Gerhard Herzberg had built a spectroscopic lab featuring the best instrument in Canada. Luise Herzberg, meanwhile, carried on her own research and assisted her husband with his work during spare moments amidst raising their two Saskatoon-born children.

Back in Germany, conditions were growing desperate for Luise Herzberg’s Jewish parents, with Stormtroopers smashing into their home during the infamous Kristallnacht. At last, with help from Murray, the Herzbergs succeeded in petitioning Canada’s immigration department to allow her parents entry into the country. They joined the Herzberg family in Saskatoon in 1939.

The Herzbergs left the U of S in 1945, but ripples are still being felt from the spring day when John Spinks received an ominous summons to the president’s office. Gerhard Herzberg was an inspirational teacher to a generation of U of S students, including Alexander Douglas (BA’39, MA’40) and Henry Taube (BSc’35, MSc’37), and he jumpstarted the university’s leadership in structural sciences.

In 1971, for his later work at the National Research Council Canada, Gerhard Herzberg was recognized with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Twelve years later, he saw his former student Taube win his own Nobel Prize: the first ever awarded to a U of S graduate.