The Classical period is considered, traditionally, the peak of artistic perfection. It represents, in many respects, a Golden Age of splendor. The Greeks had emerged from the Persian and Peloponnesian wars with Athens as a model of excellence for the other Greek city-states. To enjoy the amenities of life and indulge a little ceased to be considered softness. Life became easier and more opulent, at least for the wealthy.

This was the epoch of naturalism in art, showing men and women as they really looked and felt. Freestanding sculptures predominated--usually at least life size, often greater and grander than life. The pure white that is such a well-known trademark of Classical sculpture is not, however, true to the period. Most statues and reliefs were painted with colourful pigments and adorned with metal jewelry in a fashion we might today consider garish.

Nudity is a distinguishing characteristic of Classical Greek art. The ancient Greeks inhabited a very hot climate, and were also renowned for their athletic prowess. They found that clothing stilfed and encumbered movement, and it became traditional to wear nothing at all when competing. (The English word gymnasium is derived from the Greek word gymnos, meaning “unclothed.”) More importantly, the Greeks believed that men and women were made in the likeness of the gods. The human body was itself considered a thing of great beauty and was much admired. It was therefore the aim of the sculptor to represent man at his idealized best, to create the image of the perfect individual. It then became natural to portray gods, heroes, and athletes without clothing.

Providing a one-word definition for the art of this period is difficult, as it continued to progress over the course of about a century. For example, nudity of the female figure postdates that of the male (and only really develops fully in the Hellenistic period). Gods and goddesses appeared more and more in humanly relaxed attitudes. Sentiment was expressed by gesture and posture, action by complex composition and the suggestion of mobility: all restraint in attitude was soon eliminated.

Sculpture

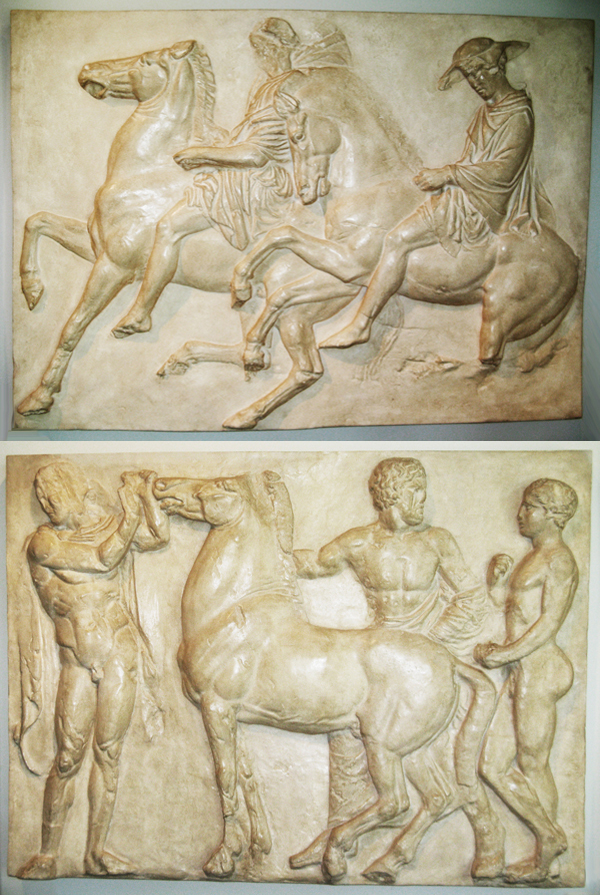

Parthenon Frieze Panels

Classical Greek

replicas: from the Louvre, Paris

date of the original: c. 442-438 BC

provenance of the original: the Parthenon, the Acropolis, Athens; now in the New Acropolis Museum, Athens

description: Panels from the west frieze of the Parthenon depicting part of the Panathenaic procession held in honour of Athena every four years. Plaster replicas; Pentelic marble originals. Each: height 103 cm, width 141 cm, depth 13 cm.

Horsemen, One Wearing the Petasos (top)

The Parthenon was the shrine of Athena Parthenos (the Maiden), and housed her lavishly decorated chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue, which stood almost 12 m high. This statue is also attributed to Pheidias. No sculptor achieved such fame in the ancient world as Pheidias, while leaving practically no concrete proofs of his accomplishments; the great statue of Athena is long lost.

This slab of the frieze represents a scene from the Panathenaic procession which took place with special solemnity every four years in honour of Athena. Young aristocrats participated in it with a cavalcade of which the scene is part. There is a contrast between the rearing horses and the serene classical calm of their riders, who remain somewhat impassive in a dynamic action. Curiously, horses, also in later epochs, are generally overdone as fiery, mettlesome steeds, and so their anatomy is made rather “horsier” than it is in reality. Necks are mightier, legs daintier, etc. On the contrary, the riders’ drapery expresses, with simplicity, the movement and attitudes taken by the horsemen.

Stableman, Horse, Nobleman and Groom (bottom)

Three men attending a horse. Extensive damage to face of stableman. Probable artists: Ictinos or Callicrates under Pheidias.

The title could also be “Preparation for the Cavalcade”, which may be a more correct guess than the preceding pedantic identification. The well composed and structured group, a difficult task on a relief, as well as the well articulated bodies and poses, bear witness to the heightened skills, experience and sensitivity of Classicism. Nonetheless, the picture remains a living tableau. It is a frozen action, not yet thawed by naturalism.

(See also: "Mourning" Athena; Nike Loosening Her Sandal.)

Nike Loosening Her Sandal

Classical Greek

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

date of the original: c. 420 BC

provenance of the original: the balustrade of the temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis, Athens; excavated by Ross in 1835; now in the New Acropolis Museum, Athens

description: Relief of a figure of Nike, winged and draped, bending to loosen her sandal. Head obliterated. Plaster replica; Pentelic marble original. Height 96 cm, width 56 cm, depth 18 cm.

This Nike is a slightly later Classical work than the Parthenon Frieze Panels, from the parapet of the temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis of Athens. The goddess is taking off her sandals before entering the temple and is just unfastening her right sandal. The perfect and graceful balance with weight on the left foot, the slightly twisted and bent torso with the adherent drapery underlining the displacement of the body, the graceful unfastening right hand, the equally graceful counterbalancing gesture of the left arm (though mutilated), and, last but not least, the elaborate drapery emphasizing the complexity of the posture, make a great work by accomplishing so much with so little.

Athena Nike is a warrior maiden, the goddess of Victory. Her temple was decreed by the Athenians in 488 BC, but was not completed until 405 BC. Part of the fifth century building program of Pericles, the diminutive temple remained relatively untouched until the 18th century when the Turks dismantled it to complete their fortress. It was reconstructed after the liberation of Greece.

A parapet was constructed around the temple in 408 BC. On the outside ran a frieze celebrating the victories of Athens in the Peloponnesian War. On each of the three sides (north, west and south) of the parapet is a seated Athena, who watches the winged Victories decorating trophies or bringing animals to sacrifice. Fragments of twenty- four slabs representing fifty figures in all were found, about one-third of the parapet frieze.

(See also: "Mourning" Athena.)

Hermes with the Infant Dionysus

Classical Greek

date of the original: mid-4th century BC

provenance of the original: discovered in AD 1877 in the cella of Heraeum, Olympia; now in the Olympia Museum, Greece

description:Male figure with legs missing from just below the knees. Right arm missing above elbow. Small, childlike figure sits on left arm. Draped trunk for support. Punch/chisel marks on the back. May be a copy of a Praxitelean original. Plaster replica; Parian marble original. Height 215 cm, width 100 cm, depth 70 cm.

This sculpture is the work of Praxiteles of Athens (c. 390-332). He seems to have been the most highly regarded sculptor in antiquity. Considered to be a “sensual” artist, Praxiteles is said to have represented with refinement the feminine body and the body of theephebe, the somewhat effeminate young man. Praxiteles was not what one could call a sculptor of gods and heroes; his work reflects the secular, worldly trend of the Late Classical epoch. (See also: Aphrodite of Cnidos; Aphrodite of Arles; Apollo Lykeios.)

Though this sculpture was found at Olympia and was certainly commissioned for that sanctuary, it is worldly in concept and effect. The Classical restraint and poise is replaced by an undulating body in a defined S-curve which defies equilibrium. While the proportions of the infant Dionysus are not quite lifelike, the inclusion of babies/children in Late Classical sculpture is significant of social changes, of the prevailing secularism and sentimentalism from this point on. (See: Child and Goose.)

The present cast was made from an unfinished statue, as is apparent from the back, which shows still unpolished traces of tools. This suggests to some that the copy in this collection is a copy of a copy, since the original would not have been unfinished. This is not necessarily logical, but much hair-splitting characterizes the discussion of such problems. In any case, it is interesting to see unfinished works as they help us to learn about ancient techniques.

Hermes, equivalent to the Roman god Mercury, was a messenger to the gods and a trickster. He is often depicted in Classical art with the herald’s wand, winged hat and boots (or sandals). Dionysus is a god associated with emotion. His devotees, mostly women, were often seized by an ecstatic state, and abandoned their homes and families to wander and dance in the mountains. At the height of their frenzy they were known to tear apart animals and devour them. (See:Maenad Rending Her Prey.) Dionysus’ Roman equivalent is Bacchus.

Head of Hygieia or Atalanta

Classical Greek

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

date of the original: c. 350 BC

provenance of the original: the Temple of Alea Athena, Piali (ancient Tegea), Greece; excavated by Mendel (AD 1900-1902); now in the National Museum, Athens

description: Head of a goddess, either Hygieia, daughter of Asklepios, or Atalanta. In the style of Scopas. Resin replica; marble original. On base: height 40 cm, width 22 cm, depth 26 cm.

The evolution of Greek sculpture was, of course, of much greater complexity than can be described here, and was not linear, as this necessarily simplified presentation might indicate. Scopas of Paros, the author of Hygieia, is one sculptor who does not quite fit into the general scheme. He was a generation younger than Pheidias (see:Parthenon Frieze Panels) , and together with the later sculptor Praxiteles (see: Aphrodite of Cnidos; Aphrodite of Arles; Hermes and the Infant Dionysus; Apollo Lykeios), these three compose the great artistic triad of the fifth and fourth centuries. Scopas was active at Tegea in Arcadia in the Peloponnesus around 370 BC as architect in charge of the construction of the temple dedicated to Athena as well as of its sculptural decor. Curiously, not only did he hold the same position as Pheidias at Athens, but there is also little direct evidence of his work.

Nevertheless, at Tegea everything bears the same stamp and we can be sure that it reflects the master’s manner. He breaks with what we usually assume to be the “serenity” of Classicism, especially in the Tegean pedimental sculpture, which teems with orgiastic, dishevelled maenads. Scopas’ dynamic figures already merge into naturalism and point further to Hellenism. Scopas is an “irregular” in the supposed evolution of Greek art, which our wishful thinking conceives as a regular, practically predetermined process admitting no deviations.

Scholars who classify Scopas only as a sculptor of Dionysian themes identify this head as that of Atalanta, a cruel sacrificer of suitors. Others see Classical serenity in it and identify it as the head of Hygieia, a virgin addressed as “mother most high” and mentioned by Pausanias as shown together with a sculpture of her father Asklepios on the same spot at Tegea.

This head, like Scopas’ others (see: Psyche of Capua; Head of Hypnos), expresses a great deal of character and does not correspond to the somewhat vacuous Classical ideal. The beauty of Hygieia results from the finesse of her narrow face and her deep-seated melancholy eyes.

Aphrodite of Cnidos

Classical Greek

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

date of the original: c. 364 BC

provenance of the original: a shrine at Cnidos, in modern-day Turkey; now in the Vatican Museum, Rome

description: Torso of a statue of Aphrodite stepping from the bath with head and extremities missing. Plaster replica; marble original. Height 68.5 cm, width 32 cm, depth 20 cm.

“To see which many have sailed to Cnidos, is the finest statue not only by Praxiteles (see also: Aphrodite of Arles; Hermes and the Infant Dionysus; Apollo Lykeios) but in the whole world.” So said Pliny the Elder, a Roman scientist and historian. The Aphrodite of Cnidos was celebrated in many stories. One tale explains that Praxiteles created both nude and draped versions of the statue for the citizens of Kos. They were horrified by the naked statue, but the people of Cnidos were excited to purchase it instead. Another story offers that a courtesan named Phryne was Praxiteles’ model for the sculpture. There is also an embarrassing anecdote about a young man who mistook the statue for a real woman and attempted to copulate with her one night.

There have been many attempts to restore the head and limbs of this version, with more or less convincing results. But a headless torso paradoxically has some advantages. The head always automatically becomes the focal point, and the eyes of the beholder always return to it. The rest, however important, remains more or less marginal. But if the head is hidden or gone, the rest comes fully and conspicuously into view. Thus we can fully appreciate the torso, which is actually the detail to be particularly admired.

With Praxiteles, the female body became an organic whole, transforming the surface anatomy into a gently rolling landscape, a chiaroscuro without sharp transitions, limits or accidents. This Aphrodite’s smooth form is rendered with all the little changing details produced by the displacement of the “soft” parts according to her posture and gesture.

She is a sort of Eve, whose long lineage will be variants on the Praxitelian theme (see: Aphrodite of Arles; Aphrodite Anadyomene; Crouching Aphrodite; Aphrodite of Melos).

Head of Hypnos

Classical Greek

replica: from the British Museum, London

date of the original: c. 350 BC

provenance of the original: near Perugia, Italy; now in the British Museum, London

description: Head with one wing protuding from right side; left wing missing. The original is a Roman copy of a Greek original by Scopas. At one time it was part of a full figure. (An almost complete marble statue of Hypnos is in the Prado museum of Madrid, Spain.) Resin replica with oxidized bronze finish; bronze original. Height 21 cm, width 41 cm, depth 22 cm.

Hypnos, the god of sleep, thought of as a winged youth “who comes softly and is sweet for men.”

There is only one wing left on this bronze Scopaic head. The face retains an air of melancholy despite the absence of its once coloured eyes, which all bronze statues had. It is also rather square, one of Scopas’ trademarks (see also: Head of Hygieia; Psyche of Capua).

Head of Eros

Classical Greek

replica: from the British Museum, London

date of the original: c. 4th century BC

provenance of the original: now in the British Museum, London

description: Head with damage to nose and chin. Probably missing body. Resin replica; marble original. Height 22.5 cm, width 13 cm, depth 14.5 cm.

Eros (Cupid), the god of love who “grew young,” at least in art. In the 4th century BC, after being depicted for centuries as a teenager, he became the little boy as represented here, and finally diminished to the size of a winged baby (the later baroque angel).

This is one of those little works whose size simply prevents them from being classified as great or from being particularly noticed.

(See also: Crouching Aphrodite; Lebes Gamikos.)

Aphrodite of Arles

Classical Greek

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

gift of: Turhan Okeren

date of the original: 4th century BC

provenance of the original: found in 1651 in the area of the Roman theatre of Arles, France; now in the Louvre, Paris

description: Standing, partially draped figure of Aphrodite. Round object in right hand, which is raised, handle of mirror in her left. Plaster replica; marble original. Height 210 cm, width 95 cm, depth 51 cm.

Mourning Athena

Classical Greek

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

gift of: The Diefenbaker Canada Centre, University of Saskatchewan

date of the original: c. 460 BC

provenance of the original: now in the Acropolis Museum, Athens

description: Bas-relief of Athena holding a spear. Resin replica; Pentelic marble original. Height 55 cm, width 32 cm, depth 5 cm.

Athena was the Greek goddess of wisdom and arts and crafts as well as a warrior goddess par excellence and patron of Athens. Mythology has it that she was born, clad in full armor, from the head of Zeus.

Her attributes include the spear, helmet and the aegis (a goat-skin shield). On her shield she had mounted the Gorgon’s head (see also:Hannibal), given to her by Perseus, which turned every being that looked at it to stone.

In this piece, Athena wears a peplos and Corinthian helmet pushed back on her forehead. She leans against her spear as her eyes look down towards a stele.

It is not clear what type of inscription this stele would have conveyed, though the somber mood of the piece suggests it may well have been funerary in nature.

(See also: Nike Loosening Her Sandal.)

Apollo Lykeios

Classical Greek

replica: from the Staatlichen Museen, Berlin

gift of: Dr Peter & Doris Bietenholz

date of the original: 370-360 BC

provenance of the original: in AD 1776, on Frederick the Great’s order, it was purchased in Rome; in AD 1826, it was acquired by the Pergamon Museum, Berlin, where it remains today

description: The Olympian god Apollo holding a lyre. Plaster replica; marble original. Height 237 cm, width 81 cm, depth 77 cm.

The Greek original of this statue is lost; it was, however, described by Lucian, who noted that the statue was located in the Lyceum, Athens’ outdoor gymnasium named after Apollo’s temple. That statue leaned on a column, a bow in his left hand with his right arm curved over his head. Coins such as the tetradrachm sometimes depict Apollo Lykeios in a similar stance.

Apollo was in fact one of the most frequently portrayed male deities in the Late Classical period. Some thirty copies of the Apollo Lykeios sculpture itself survive, indicating that the original was a well-known cult image.

This particular statue is a Roman copy of the Greek original. The original has been attributed to Praxiteles, as its style closely resembles that of Hermes with the Infant Dionysus (see also: Aphrodite of Cnidos; Aphrodite of Arles). In the 18th century, Bartolomeo Cavaceppi restored this statue’s arms, left leg and head. The head was in fact taken from a statue of Apollo Kitharoidos (Apollo with the kithara).

Pottery

Lebes Gamikos

Classical Greek (Red-Figure Pottery)

replica: from the Hermitage Museum, Leningrad

date of the original: middle 4th century BC

provenance of the original: Kerch (ancient Pantikapaion), Greece

description: Red-figure nuptial vessel. Original by the Marsyas Painter. Pottery replica; pottery original. Height 46 cm, diameter 30 cm.

The lebes gamikos is a wedding bowl distinguishable by its high looping handles set on either shoulder. Like the loutrophorous, this vessel would likely have been used to bring water for the ritual bridal bath. Using the red-figure technique, the artist of this vessel, the “Marsyas Painter,” depicts a nuptial scene including the bride and her female attendants, as well as various objects related to the wedding ceremony. It is likely that this is a portrayal of the day after the wedding ceremony, the epaulia, when the bride, now unveiled, sits in her new home and is greeted by guests bearing gifts. In the centre of the scene the young bride is depicted seated on a gilded chair, draped in a himation with little Eros (see: Head of Eros) on her lap. A young girl offers the bride a lekanis or covered dish, while others prepare to offer her such items as small chests, a nuptial lebes, a pyxis (see:Ivory Pyxis), and a basket.

(See also: Woman/Maiden Alabastron; Maiden/Muse Lekythos.)

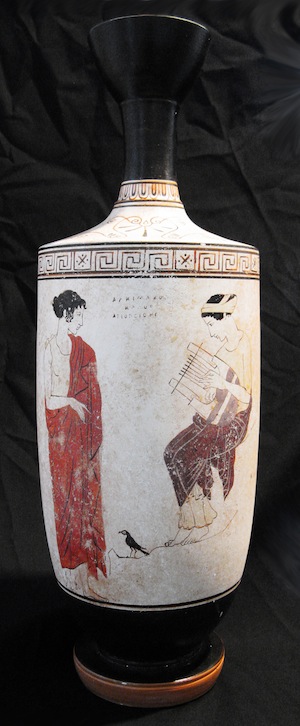

Maiden/Muse Lekythos

Transitional Greek (Attic White-Ground Pottery)

replica: from World Treasures, California

date of the original: c. 445 BC

provenance of the original: a girl's grave; later in a private collection of Lugano; now in the Antikensammlungen, Munich

description: White ground lekythos picturing two women on Mt. Helicon. One (muse) seated on rock, inscribed H IKON, and playing the kithara. Left, other woman standing, dressed in sleeveless chiton. Between the two, the inscription A IO EI HC KA OC A KIMXO. Pottery replica; pottery original. Height 40.5 cm, diameter 13 cm.

In white-ground painting a white coating was applied to the vase before black or red figures (depending upon the period) were painted on. White-ground pottery was restricted to lekythoi by the fifth century BC, and were made popular by the Achilles Painter, a workshop whose most famous pieces bore images of the myth of the hero Achilles. The white-ground glaze was too temperamental to be used for utilitarian pottery like cups and bowls, since the delicately painted surface could be easily damaged.

These vases had therefore an ornamental function, usually associated with funerary rituals. Lekythoi filled with perfumes were placed around the corpse; others were set along the approach to the grave or beside the tomb. The illustrations often recounted scenes from the life of the deceased.

Our lekythos features a muse, perhaps Erato, playing the kithara on Mount Helicon, while another woman (perhaps another muse) stands by. Found in a young girl’s grave, the deceased may have been noted for her musical ability. Between the women the inscription, added by the potter, reads “Axiopeithes, the son of Alkimachos, is beautiful.”

(See also: Woman/Maiden Alabastron; Lebes Gamikos; Clay Lekythos; Terracotta Lekythos.)