A new Greek world sprang up in the wake of Alexander the Great’s conquests, expanded and prosperous, new in its political constitution and social structure. The kingdoms of the Hellenistic world were certainly nominally Greek, ruled by the descendants of Alexander’s generals--the Antigonids in Macedon and Greece, the Ptolemies in Egypt, the Seleucids in Syria and Mesopotamia, and the Attalids in Anatolia. However, each region quickly developed its own unique culture, a blend of local traditions with the ideals, beliefs and art of the Greeks. Ancient Near Eastern and Egyptian creative traditions influenced the Classical conventions, producing the Hellenistic synthesis.

Besides the reiteration of Greek public patronage, a considerable and growing number of the citizens of the Hellenistic world became clients and patrons of artists. They no longer regularly erected monuments to gods or rulers, but were more interested in art that was secular in nature, neither religious nor regal--art to adorn private homes as well as public space.

Hellenistic art can be defined by its intense emotional appeal and growing emphasis on individual character. Freestanding sculpture and reliefs continued to be admired, and artists pushed the detailing of anatomy, pose, clothing, and expression ever further. Sculpture became “hyperrealistic,” a term referring to the nigh-impossible exaggeration of twists, turns, and musculature apparent in the greatest works of Hellenistic art.

Scupture

Three Graces

Hellenistic

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

date of the original: middle 3rd century BC

provenance of the original: now in the Louvre, Paris

description: Three nude female figures entwined executing a dance. Heads and feet missing. Plaster replica; marble original. Height 40.5 cm, width 38.5 cm, depth 8 cm.

Aglaia (Radiance), Euphrosyne (Joy), and Thalia (Fruitfulness) presided over all beauty and charm in nature and humanity. The three sisters gracefully execute a voluptuous dance.

It is a composition of great simplicity, obtaining its rhythm from the sinuous bodies. Each body, no doubt of Praxitelian inspiration (see:Aphrodite of Cnidos; Aphrodite of Arles), is in itself an accomplishment. The Hellenistic trend converted the once coy and fully dressed sisters into an erotic show while still demonstrating the beauty of the feminine nude beyond all sensuality.

Maenad Rending Her Prey

Hellenistic

replica: from the British Museum, London

date of the original: 1st century BC to 1st century AD

provenance of the original: now in the British Museum, London

description: Relief depicting a frenzied maenad, draped, grasping a knife over her head in right hand, swinging severed hind quarters of a roe in the left. Resin replica; Roman marble original. Height 42.5 cm, width 22.5 cm, depth 3 cm.

A Hellenistic slab representing a maenad or worshipper of Dionysus in a frenzied state tearing a roe to pieces. Her delicate slim body, apparent under the thin veil which leaves one breast and arm bare, tiptoes gently in a whirl of cloth. Yet she is engaged in ferocious action. She symbolizes the restrained, rational Apollonian attitude together with its antithesis, the emotional, irrational Dionysian (see also: Hermes with the Infant Dionysus).

Child and Goose

Hellenistic

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

date of the original: middle 2nd century BC

provenance of the original: found in AD 1789 in Rome; transferred to the palais Braschi; now in the Louvre, Paris

description: Figure of a small chubby boy grasping a large goose around the neck. (Similar statues in the Museo Capitolino and the Vatican Museum.) Plaster replica; Roman marble copy of a bronze original. Height 94 cm, width 45 cm, depth 80 cm.

This little boy seems to be struggling with the huge bird rather than strangling it, as some scholars suggest. The work, dated from the beginning of the second century BC, is representative of the trends and tastes of Hellenistic society. The pudgy little boy’s babyish cuteness is studiously emphasized.

Many identical copies of him already existed in antiquity, which illustrates the type’s great popularity. This one is attributed to Boethus of Chalcedon.

Socrates

Hellenistic

replica: from the British Museum, London

date of the original: c. 200 BC - AD 100

provenance of the original: Alexandria, Egypt; now in the British Museum, London

description: Togate statuette. Resin replica (on wooden base), with granular finish on skin; marble original. The original is a small-scale Roman copy of an earlier Greek portrait statue (c. 399 BC). On base: height 31.5 cm, width 11.5 cm, depth 6 cm.

This is not a faithful portrait of the great philosopher. The statuette, a small-scale Roman copy of an imagined Greek portrait, is eminently “psychological” with many hints to Socrates’ features about which the sculptor had probably heard only oral testimonies.

It expresses adequately the idea we have of Socrates. If the subject of the statuette were not known, it would still be recognized as a psychological portrait.

Aphrodite Anadyomene

Hellenistic

replica: from Alva Museum Replicas, New York

permanent loan: from the Dept. of Art and Art History, University of Saskatchewan

date of the original: 1st century BC

provenance of the original: black basalt version now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

description: Torso of the Aphrodite of Cnidos type. Reduced black resin replica, on a variegated marble stand; unknown original of granite. On base: height 50 cm, width 22 cm, depth 15 cm.

This Aphrodite is called Anadyomene, or Aphrodite Rising from the Foam, or The Birth of Venus. She is a reduced copy of a Roman version of the original Greek prototype and, of course, a visible progeny of the Aphrodite of Cnidos, though the original is shown as stepping out of or into the bath. This Aphrodite stood on a dolphin, or porpoise, whose tail fins can still be seen at the back of her left leg.

(See also: Aphrodite of Arles; Aphrodite of Melos; Crouching Aphrodite.)

Psyche of Capua

Hellenistic

replica: 19th century AD

gift of: Edward and Caroline Kennedy

date of the original: c. 1st century B.C.

provenance of the original: the amphitheatre of Capua, Italy; now in the National Museum, Naples

description: Bust of a goddess. Head bent down and right, torso extending to solar plexis, top of head sheared. Marble replica with smoke damage making the surface yellowish. Repaired to reconnect head to torso. Original has badly damaged torso to below the waist. On base: height 66 cm, width 50 cm, depth 25 cm.

Found badly mutilated in the amphitheatre at Capua, this sculpture is incorrectly named and more likely represents Aphrodite (see also:Aphrodite of Cnidos; Aphrodite of Arles; Aphrodite of Melos; Aphrodite Anadyomene; Crouching Aphrodite). Earlier believed to be by Praxiteles (see also: Hermes and the Infant Dionysus; Apollo Lykeios), it is rather a copy after a work by Scopas, having characteristic sloping shoulders, globe-shaped breasts, peculiar mouth and dilated nostrils, the ear slanting back with the lobe close to the head. (See also: Head of Hypnos; Head of Hygieia.)

The figure originally leaned its weight on the right leg and drew the drapery, which covered the lower part of the body, over the left shoulder with the left hand. The head, turned to the right and bent down, suggests the figure may have been part of a group, perhaps with Eros (see: Head of Eros) holding a mirror.

Aphrodite of Melos (Venus de Milo)

Hellenistic

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

date of the original: c. 2nd century BC

provenance of the original: found in AD 1820 on the island of Melos and given to Louis XVIII who presented it to the Louvre in AD 1821, where it remains today

description: Figure of Aphrodite semi-draped. Both arms missing below the shoulder. Original had metal earrings. Plaster replica; original in two blocks of Parian marble which meet just above the drapery. Height 215 cm, width 59 cm, depth 60 cm.

This is probably a second century BC refined version of the Aphrodite of Cnidos ancestress. The more stocky Venus de Milo, as she is better known, like the Aphrodite Anadyomene, is considerably more articulate. Her lifted left leg, withholding the slipping drapery, suggests at the same time an energetic movement to secure balance. It energizes the whole attitude and enhances the grace of the daintier body.

A direct comparison of the Cnidos version with the Melos version shows how much more subtle the latter is in all details and makes clear the degree of refinement achieved by Hellenistic art--of which she is an eminent representative.

(See also: Crouching Aphrodite; Aphrodite of Arles.)

Eos in Her Chariot

Hellenistic

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

gift of: Mr. Byng Thayer in memory of Helen Thayer

date of the original: 1st century BC

provenance of the original: Herculaneum; now in the collection of the Duc de Loule in the Lisbon Museum, Lisbon

description: Relief showing Eos driving a quadriga. Her lover (Tithonus or Cephalus) at the horses’ heads. Plaster replica; marble original. Height 74 cm, width 143 cm, depth 9 cm.

This is a neo-Attic relief dating from the first century BC, but which is itself a replica of a fourth century prototype. Fragments of a twin relief can be seen in the House of Telephus in Herculaneum. Aurora or Eos, the dawn goddess, usually depicted in a two-horse chariot (biga) drawn by Lampos and Phaeton (Shiner and Bright), was the sister of Helios (the Sun) and led him each day into the Heavens. From the fifth century she was often depicted pursuing or carrying off Cephalus or Tithonus, her lovers. According to Homer, her son Memnon was killed by Achilles in the Trojan war; the morning dew is said to be the tears she shed for him.

Crouching Aphrodite

Hellenistic

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

in memory of: Nicholas Gyenes

date of the original: middle 3rd century BC

provenance of the original: found near Vienne in AD 1830; now in the Louvre, Paris

description: Aphrodite in crouching position. Head missing and right arm from middle of upper arm, left arm at shoulder. Small hand of another figure on back. Plaster replica; original by Diodalsas of Bithynia, probably of bronze, of which this is a Roman copy in Pyrimidal marble. On base: height 115 cm, width 74 cm, depth 51 cm.

The Crouching Aphrodite, sometimes called the Venus of Vienne, is a Roman copy of a Greek original. In fact, the original was freely copied with many variations.

The Greeks had long been preoccupied with the beauty of the male form (see: Apollo Lykeios; Hermes with the Infant Dionysus; Borghese Warrior or Gladiator), but it was only in the Hellenistic period that the female form became firmly established as an artistic subject. A descendant of the Aphrodite of Cnidos, after which Aphrodite was usually represented nude and at some point in the process of bathing (see also: Aphrodite Anadyomene; Aphrodite of Melos; Aphrodite of Arles), this Aphrodite is plump and seductive. She crouches, perhaps to receive a shower of water, and on her back are the remains of the left hand of Eros (see: Head of Eros) who flew nearby, possibly holding her mirror.

Borghese Gladiator or Warrior

Hellenistic

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

bequest of: Edward James Durnin

date of the original: early 1st century BC

provenance of the original: found in AD 1611 at Nettuno, near Anzio, Italy; by AD 1613 in Borghese collection; purchased in AD 1807 by Napoleon

description: Figure of a warrior, plunging forward, left arm extended upwards with remains of shield on forearm. Head facing left, right arm down and behind, hilt of sword in right hand. Greek inscription on trunk. Plaster replica; Pentelic marble original. (Much copied in bronze.) Length head to heel 199 cm, height 163 cm, depth 79 cm.

The Borghese gladiator bears the signature of the little-known sculptor Agasias of Ephesus on the trunk of the tree which supports the figure. The warrior plunges forward, the body straining and stretching, to parry a blow, probably from above, a shield (now missing) on his left arm, a sword (now missing) in his right hand. Viewed from the side, the long, almost too-straight diagonal thrust and the arrangement of torso and limbs seem confined to a one-dimensional frame. But the two-dimensional aspects of the left arm, which leaves the body at a sharp angle, and the right arm pulling the torso in a strong twist, are evident from a frontal view. The muscles and tendons are too abundant and overly defined; this is the late Hellenistic tendency toward hyperrealistic exaggeration of the male figure’s structure (see for comparison: Apollo Lykeios; Hermes and the Infant Dionysus).

The inscription reads “Agasias, son of Dositheos of Ephesus, made (this).”

Masks

Theatrical Mask

Hellenistic

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

date of the original: 4th century BC

provenance of the original: now in the Louvre, Paris

description: A comedic theatrical mask (see also: Clay Comic Mask; Marble Theatrical Mask). Reduced-scale ornamental resin replica; terracotta original. Height 13 cm, width 12 cm, depth 6 cm.

The theatre was synonymous with the worship of the god Dionysus: god of wine, revelry and cathartic release. The mask symbolized the power of Dionysus (see: Hermes and the Infant Dionysus)--the transformation of an individual from the state of reserve to one of frenzy (see: Maenad Rending Her Prey). The cult of Dionysus sought to give reign to the darker persona of an individual.

(See also: Bronze Tragic Theatrical Mask; Clay Tragic Mask.)

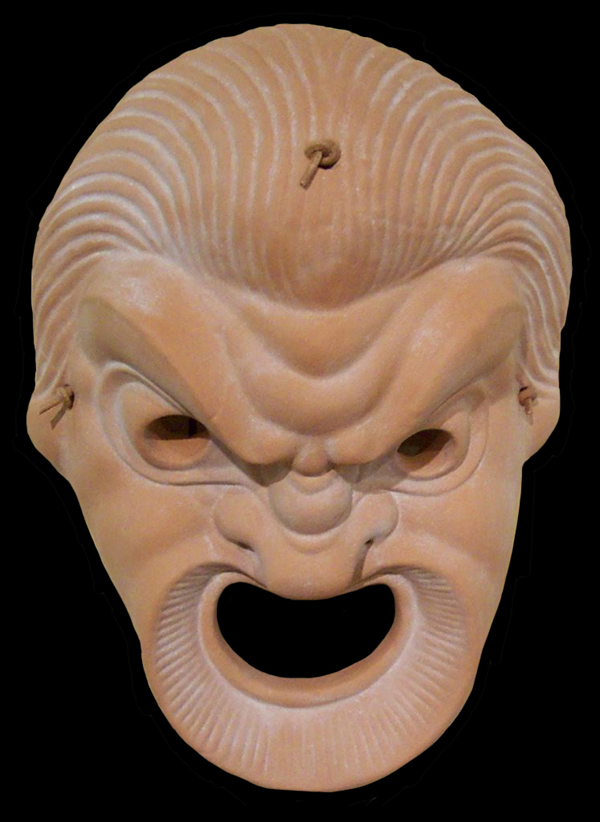

Clay Comic Mask

Hellenistic

replica: from the Greek Ministry of Culture, Athens

gift of: Dept. of Classics, University of Saskatchewan

date of the original: 3rd century AD

provenance of the original: the Ancient Agora, Athens; now in the Agora Museum, Athens

description: Comedic theatrical mask (see also: Theatrical Mask; Marble Theatrical Mask) with open eyes and mouth holes. Plaster replica; terracotta original. The original is a later (Roman) representation of an ancient Greek theatrical mask. Height 27 cm, width 19 cm, depth 10.5 cm.

These two exhibits--the Clay Comic and Tragic Masks--represent a continued fondness during the Roman period for Greek theatrical ornamentation. This is evidenced, for example, by the fourth period of wall paintings found at Pompeii, and Gnathian ware (a late Roman pottery style), both of which exhibit the use of elaborate theatre imagery, curtains, pillars, and masks, for the adornment of household objects. (See also: Bronze Tragic Theatrical Mask.)

Clay Tragic Mask

Hellenistic

replica: from the Greek Ministry of Culture, Athens

gift of: Dept. of Classics, University of Saskatchewan

date of the original: first half of 3rd century AD

provenance of the original: the Ancient Agora, Athens; now in the Agora Museum, Athens

description: Tragic theatrical mask (see also: Bronze Tragic Theatrical Mask) with open eye holes and closed mouth. Plaster replica; terracotta original. The original is a later (Roman) representation of an ancient Greek theatrical mask. Height 21 cm, width 17 cm, depth 7.5 cm.

These two exhibits--the Clay Comic and Tragic Masks--represent a continued fondness during the Roman period for Greek theatrical ornamentation. This is evidenced, for example, by the fourth period of wall paintings found at Pompeii, and Gnathian ware (a late Roman pottery style), both of which exhibit the use of elaborate theatre imagery, curtains, pillars, and masks, for the adornment of household objects. (See also: Theatrical Mask; Marble Theatrical Mask.)

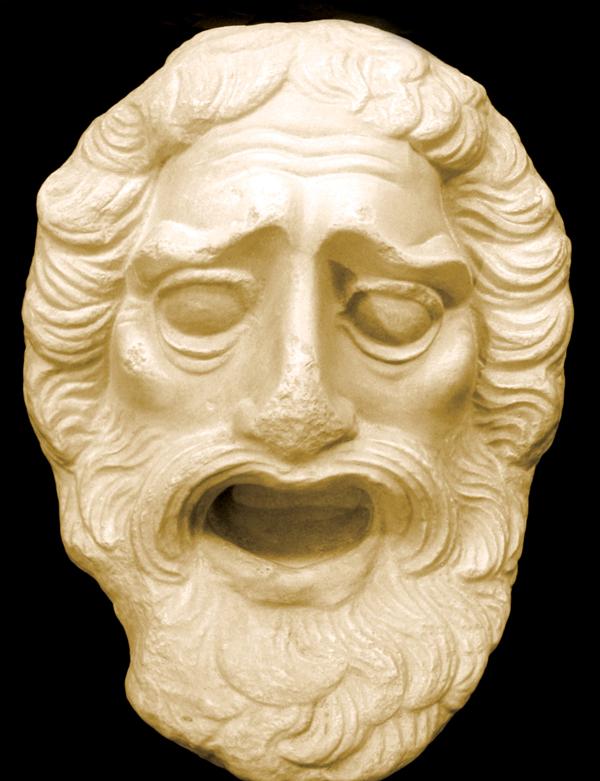

Bronze Tragic Theatrical Mask

Hellenistic

replica: from the Greek Ministry of Culture, Athens

gift of: Dept. of Classics, University of Saskatchewan

date of the original: 4th century BC

provenance of the original: now in the Piraeus Museum

description: Tragic theatrical mask (see also: Clay Tragic Mask) with open eye and mouth holes. Plaster replica with verdigris patina;bronze original. Height 38 cm, width 34 cm, depth 25 cm.

This exhibit is earlier in date than the other masks. The original piece was found in a warehouse in Piraeus, which had likely been burnt during the Roman general Sulla’s attack in 86 BC.

Many of the characteristics of Hellenistic theatrical masks (see also:Theatrical Mask; Clay Comic Mask; Marble Theatrical Mask) are in evidence here, including the large, exaggerated mouth and raised forehead. Obviously its size and weight would have made it impossible to wear in a theatrical production, indicating that it was deocrative in nature.

Marble Theatrical Mask

Hellenistic

replica: from the Greek Ministry of Culture, Athens

gift of: Dept. of Classics, University of Saskatchewan

date of the original: 1st century BC

provenance of the original: near the Stoa of Attalus in the Athenian Agora; now in the National Archaeology Museum, Athens

description: Theatrical mask with closed eyes/mouth. Plaster replica; marble original. Height 29 cm, width 20.5 cm, depth 16.5 cm.

This mask represents a character from New Comedy. The term “New Comedy” relates to the comedic plays of the fourth and third centuries BC, as opposed to “Old Comedy,” which is associated with plays of the fifth century BC.

The best known New Comedic author was Menander, who wrote plays which depicted humorous aspects of daily life. We know from ancient author Julius Pollox that there were some forty-four types of comedic masks. (See also: Clay Comic Mask; Theatrical Mask.)

(See also: Bronze Tragic Theatrical Mask; Clay Tragic Mask.)

Pottery

Storage Amphora

Hellenistic

original

gift of: Peter and Myriam Golf

date: c. third century BC

provenance: eastern Mediterranean; purchased by the donors

description: A fully intact ancient Greek transport amphora. Baked clay with marine encrustations. Height 80 cm, diameter 29 cm.

This type of vessel was used widely thorughout the Mediterranean and Near Eastern worlds to facilitate the trade of such popular commodities as olive oil and wine.

As is typical of amphorae, the vessel is pointed at its base and would have lain on its side in the bottom of a boat.

(See also: Small Black Figure Amphora; Funeral Dancers Amphora.)