The Romans grew from monarchy to republic to become one of the greatest empires the world has ever seen. The Romans started as one of many groups of indigenous Italians, but over the course of centuries became a sprawling multicultural civilization. They conquered to the east, west, north and south, imposing Roman values and order at the highest levels, but also allowing each subjugated region to retain its local character. Roman civilization is sometimes considered to peak at the time of Augustus (first century BC to first century AD), the transitional phase during which Rome shifted from Republic to Empire. Much extant, recognizably Roman art dates from the Imperial period.

The unique nature of what is “Roman” leads us to ask, “Is there a Roman art?” There is certainly a rhetorical device in the question, but it does highlight a problematic point. At the moment from which the label “Roman” started to be attached to artistic activity on Italian soil, Greek--and later, Hellenistic--art held sway over it. To make a long and still debated story short, Greek art was remodeled and transformed into a form that was inherently Roman, expressing and reflecting Roman reality, though the artist was often Greek. Where the Greeks admired and exalted the human form, the Romans used their art to pay homage to their political, social and religious institutions. They commemorated events and glorified political heroes in the form of busts, statues or slabs set into the walls of buildings or architectural monuments. We owe to Roman art a remarkable series of portraits with detailed features and expressive character, which also bear witness to the fashion of the particular reign.

We also owe the survival of the great works of Classical and Hellenistic art to the Romans, for the Greek sculptors of the Roman world probably made the copies which are the origin of most of our collection. Some even signed their name, recommending their workshop but having no pretence to authorship. Actually, the prestige of earlier Greek works and the demand for their copies were such that sheer copying was much better rewarded than was original creation.

Sculpture

Hannibal

Roman

original

gift of: Judge John C. Currelly, in honour of his mother, Mary Newton Currelly.

date: 17th century AD

provenance: first sold at auction in 1939

description: Bronze bust in baroque style; heavy black patina. Man with curly hair, wearing cuirass with Gorgon head in center, mounted on a turned marble base. Height 66 cm, width 37 cm, depth 27.5 cm.

The inventory of the works of François Girardon (AD 1628-1715, sculptor to Louis XIV and decorator of the palace at Versailles; see also Aphrodite of Arles), indicates that a bronze bust of Hannibal was once in the collection. Donated to the Louvre at one time, its whereabouts were later unknown and this bronze may indeed be that very sculpture. It bears a striking resemblance to the engraving in Girardon’s inventory, though it may also be a copy of Girardon’s Hannibal done by Sebastien Slodtz (1655-1726), Girardon’s student and protegé.

The bust is, nonetheless, an original seventeenth century bronze portrait. It is, according to Girardon’s inventory, modelled after some ancient portrait of Hannibal. This is difficult to prove, however, since no portraits of Hannibal, not even on coinage, have survived the ancient world. There is however a remarkable similarity between this work and the portraits of the Severan and Antonine emperors, both in the facial features and in the genre.

Hannibal, a Carthaginian general, is considered to be one of the world’s greatest generals, and is often compared to Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar. Hannibal came very close to defeating the Romans during the Second Punic War (218-201 BC). He crossed the Alps into Italy with his forces and achieved a series of victories against the Romans, including the Battle of Cannae (216 BC), one of the worst military defeats the Romans had ever known.

However, the Romans refused to acknowledge defeat and managed to renew their forces, thereby enabling them to drive Hannibal out of Italy. Hannibal was defeated on African soil at the Battle of Zama (202 BC) by the Roman general Scipio Africanus.

(See also: Trajan; Gaius or Lucius Caesar; Livia.)

Augustus Bevilacqua

Roman

replica: the Louvre, Paris

gift of: Friends of the Museum

date of the original: early 1st century CE

provenance of the original: Bevilacqua Palace, Verona

description: The Augustus Bevilacqua gets its name from the Bevilacqua Palace in Verona where it was housed until 1811 when it was purchased by King Ludwig I and moved to the Glyptothek in Munich where it currently resides. The original version of this replica bust is thought to be one of many copies that were disseminated throughout the Roman Empire during Augustus’ reign as emperor.

In this portrait, the wreath Augustus is wearing is called the corona civica, or ‘civic crown’, which is a crown made of oak leaves. The oak tree was sacred to the god Jupiter. The corona civica was the second highest military decoration in Rome and was given to a Roman citizen who had saved the life of another Roman citizen or had held ground against the enemy in battle. Augustus was awarded the crown in 27 BCE, not in recognition of having saved one citizen of Rome, but for saving all the citizens of Rome through his defeat of Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE. His victory brought decades of civil war to an end.

In recognition of Augustus’ victories and the resulting peace, the Senate of Rome also commissioned the building of the Ara Pacis Augustae, or ‘Altar of Augustan Peace’, which was dedicated in 9 BCE. A panel from the Ara Pacis Augustae, which depicts a procession of Imperial family members, is also a part of the Museum’s collection.

Augustus ruled from 27 BCE until his death in 14 CE. The year 2014 marks not only the 40th Anniversary of the Museum of Antiquities, but also the 2,000th anniversary of Augustus’ death. The Augustus Bevilacqua was acquired from l’Atelier de moulage du Musée du Louvre in Paris, France to commemorate the Museum of Antiquities’ 40th Anniversary. The purchase of this bust was made possible through the kind donations of many supporters of the Museum. The acquisition of this bust fills a noticeable void in the Museum’s collection of portraits of Roman emperors. Museum visitors can now look upon the face of one of the most famous and historically significant emperors from ancient Rome.

Livia

Roman

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

date of the original: c. 11 BC

provenance of the original: formerly in the collection of Louis Fould; now in the Louvre, Paris

description: Head of a woman to base of neck finished in black. Plaster replica; dark grey basanite original. On base: height 48 cm, width 22 cm, depth 2.5 cm.

This bust depicts Livia, the second wife of Augustus (see also: Panel from the Ara Pacis Augustae; Coins of Augustus), with her hair in a nodus coiffure. This particular type of portrait was common throughout the reigns of Augustus and Tiberius, Livia’s son.

As wife to the emperor, Liva diligently represented herself, and was represented as, the archetypal Roman matron. In this depiction she wears no hair adornment or article of jewellery. This may well be significant, reflecting an initiative of Augustus (the Oppian Law) which aimed to curtail the extravagance of the aristocratic women of Rome. Though Livia may have appeared the devoted and traditional wife and mother, she was nevertheless active and influential in the political life of the Empire, if perhaps more from behind-the-scenes.

This piece was formerly identified as a bust of Octavia, sister of Augustus and wife of Mark Antony (see: Coins of Marcus Antonius). Like Livia, Octavia too was portrayed with the proud matronly simplicity inherent in the Augustan policy towards family life.

(See also: Gaius or Lucius Caesar; Trajan; Hannibal.)

Gaius or Lucius Caesar

Roman

replica: from the British Museum, London

date of the original: early 1st century AD

provenance of the original: now in the British Museum, London

description: Head of youth to base of neck. Resemblance to the official portraiture of Augustus (see also: Panel from the Ara Pacis Augustae; Coins of Augustus), with whom it was originally identified. Subsequent reclassification to either Gaius or Lucius Caesar. Resin replica; marble original. On base: height 38 cm, width 20 cm, depth 23 cm.

Roman civilization has not been highly praised for original artistic achievement. In one aspect however, namely Roman portrait sculpture, it has met with great approval and admiration.

Roman domination in the western world was achieved through strong political and military organization. The Roman citizen gained reputation and status not only through his own political and military achievement but through that of his ancestors. From Republican times, therefore, it was important for the prominent individual to illustrate his lineage by some obvious means. Portrait busts (see: Livia; Trajan; Hannibal) soon came into prominence. They could be found in the houses of upper class citizens (patricians), composing a sort of “Hall of Fame” of celebrated ancestors.

In Roman funerary practice (handed down by the Etruscans) these portraits and a portrait of the deceased were carried in the funerary procession. This peculiar attention given to the portrait was unknown in earlier Greece, while in Rome it continued until the end of the Empire. A considerable number of exquisite portraits, which have lost nothing of their impact after millennia, have survived.

Gaius and Lucius, the two eldest sons of Augustus’ only child Julia, were the emperor’s chosen heirs. To familiarize the public, and especially the army, with the idea of a ruling dynasty and with the identity of chosen successors, they were made to look like the emperor in their official portraits. While this strengthened the validity of their claims to rule, it also suppressed their identities so strongly that they are difficult to tell apart. This bust is rendered with the greatest possible simplicity, making it a quietly powerful work.

Panel from the Ara Pacis Augustae

Roman

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

date of the original: 9 BC

provenance of the original: originally erected in the Campus Martius, Rome; original found in AD 1568 on site of Palais Fiano; in Collection Campana, Palais Aldobrandini in AD 1864; now located near the Mausoleum of Augustus, Rome

description: Relief depicting part of a procession: seven persons draped and two children. Damage to the original reflected on the upper left corner extending across the top to the upper right. Only one adult head survives. Damage also to bottom of left side. Plaster relief; marble original. Height 120 cm, width 150 cm, depth 23 cm.

The Ara Pacis Augustae or the Altar of Augustan Peace was voted by Roman Senate in 13 BC to honour Augustus’ (see also: Coins of Augustus) safe return from Spain and Gaul; it was dedicated in Campus Martius in 9 BC. It comemmorated the establishment of peace, the Pax Augusta (“Augustan Peace”).

The fragment represents part of the imperial procession at the inaugural sacrificial ceremony. The persons taking part in the procession are members of the imperial family (see: Livia; Gaius or Lucius Caesar). They are rendered according to their importance in high or low relief.

The altar itself is surrounded by four “walls” of panels, carved in relief both inside and out. Other panels depict important events and figures in Roman belief and history, chosen to complement Augustus’ political agenda.

Trajan

Roman

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

date of the original: 98-117 AD

provenance of the original: discovered in the Albini collection, Rome; now in the Louvre, Paris

description: Bust to mid-chest including shoulders; mounted on a pedestal. Plaster replica; Luna marble original. On base: height 70 cm, width 54 cm, depth 27 cm.

The emperor Trajan (see: Coins of Trajan) appears gentle, wise, humble and sedate because of the Classical simplicity with which he appears here--or because we have been told of his characteristics by ancient sources. The latter do influence one’s judgement, but the emperor does seem to have been as poised as the manner in which he is expressed.

Trajan’s ethos and his style certainly seem to correspond. He was considered an exceptional emperor, having the personal qualities of simplicity and modesty. He was a natural leader and a favourite with the army and the senatorial classes. His economical adminstration and humanitarian social policies made him generally popular.

(See also: Livia; Gaius or Lucius Caesar; Hannibal.)

Hadrian

Roman

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

gift of: Judith Rice Henderson and T.Y. Henderson

date of the original: 125-130 AD

provenance of the original: Unknown; now in the Louvre, Paris

description: Bust to mid-chest including shoulders, draped; mounted on a pedestal. Plaster replica. On base: height 90 cm, width 70 cm, depth 37cm.

The emperor Hadrian (see: Coins of Hadrian)

Hadrian, born in 76 into a Roman family with Spanish connections pursued the standard senatorial career, undertaking both civilian offices and military posts that offered wide experiences. A favorite of Trajan's wife Pompeia Plotina, the two shared a strong philosophic and cultural interest. When Trajan died in 117 without a clear successor in place, the Senate hailed Hadrian as the adopted son of Trajan and thus the next emperor of Rome.

(See also: Livia; Gaius or Lucius Caesar; Hannibal; Trajan.)

Marcus Aurelius

Roman

replica: from the Ephesus Archaeological Museum, Turkey

date of the original: AD 2nd century

provenance of the original: Turkey; now in the Ephesus Archaeological Museum, Turkey.

description: Bust to mid-chest including shoulders, draped; mounted on a pedestal. Unfinished resin replica. On base: height 81 cm, width 49 cm, depth 53cm.

The emperor Marcus Aurelius (see: Coins of Marcus Aurelius)

Born in Rome in 121, Maucus Aurelius knew from an early age that he was destined for high public office. The Emperor Hadrian took note early of his promise and encouraged his development through distinctions and the tutelage of the Empire's best scholars and teachers. He studied a variety of subjects such as rhetoric, essential for a high career, and philosophy.

When Hadrian adopted Antoninus Pius as his heir, he subsequently had Antoninus Pius adopt sons both Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, putting in place a second generation of successors. Thus upon Antoninus's death in 161, the Senate inaugurated Marcus Aurelius, the superior of the two, as emperor. He in turn invested Lucius Verus with powers nearly equal to his own, thereby entrusting Rome to a dual regime.

(See also: Trajan; Hadrian.)

Rain Miracle Scene from the Column of Marcus Aurelius

Roman

replica: by artist Carrie Allen

date of the original: c. AD 176-193

provenance of the original: Italy

description: Rain Miracle Scene from the Column of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Plaster and wood replica.

The Column of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius was commissioned to celebrate his triumph in 176 over the Marcomanni tribe and their allies, the Sarmatians and the Quadi, whose territories rested on Rome's northern Danube frontier. The column was completed sometime after his death in 180 during the reign of his son Commodus, though the exact date is not known. It was not dedicated until 193, the first year of the reign of Septimius Severus.

The column, which stood on the Campus Martius by the Via Lata, was modeled after Trajan's column. The part visible today measures about 30 m in height; in its prime, before the rising ground level covered the base, and while it was still surmounted by a statue of Marcus Aurelius - replaced in the Renaissance with a statue of St. Paul - the monument as a while may have approached 50 m in height. The column consists of 26 drums made of Luna marble with a hollow interior and stairs that lead up to the top. Sculptures in high relief spiral around column 21 times, presenting 116 scenes depicting Marcus Aurelius's campaigns against Germanic tribes threatening the Danube frontier. In contrast to the scenes on the Column of Trajan, which emphasize the theme of conquest, those on the column of Marcus focus on the destruction of the enemy.

Perhaps the most famous of the panels is scene XVI. It depicts how the Roman army, surrounded by Quadi and "in a terrible plight from fatigue, wounds, the heat of the sun, and thirst" (Dio 72[71].8.3), was saved and the enemy destroyed thanks to a "Rain Miracle." This panel gives the official Roman interpretation: Heaven had intervened on the Roman side. The miraculous deluge is personified on the column as an ancient god of colossal size from whose locks and outstretched arms rain pours down onto the battlefield.

The question of which god performed the "Rain Miracle" inspired opposing pagan and Christian accounts. Dio knew of a pagan report that credited Hermes of the Air (Hermes Aerio) (72[71].8.4). For the Christian apologist Tertullian the miracle was a response of his god to prayers of Christian soldiers who happened to be fighting in the Roman army (Apologeticus 5.6). Tertullian cited as his source a letter of Marcus Aurelius; this can hardly have been a genuine letter. Nonetheless, the widespread view existed that a prayer of Marcus Aurelius incited the occurance of the miracle, which was considered evidence of divine support for his reign.

(See also: Trajan; Hadrian; Marcus Aurelius.)

Nubian Boy Unguent Jar

Roman

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

gift of: Professor Gary Hanson

date of the original: 2nd century AD

provenance of the original: now in the Musée des Beaux Arts, Lyons

description: Unguent jar in the shape of a bust of a young Nubian boy, with elaborate headdress; hinge remaining at top of head with cylindrical opening. Resin replica with verdigris finish; bronze original. Height 11.5 cm, width 8.5 cm, depth 7 cm.

Receptacles for unguents or perfumed oils were widespread during the Roman period. They took many shapes (see: Glass Unguentarium), as perfumed oils had many uses. In addition to being used simply as body perfume, oils were used to coat the skin before exercise (after which they were removed with a strigil), as libations to the gods, and in funeral rites.

This graceful, elegantly proportioned portrait of a young African boy illustrates the fusion between the two cultures, Roman and Egyptian, from which it originated. The portrait image, surmounted by an elaborate wig, recall the sculptures of Upper Egypt at a much earlier period.

Dating from the Punic Wars with Carthage (see: Hannibal), the Romans were active in North Africa. Their victories against various African tribes resulted in the capture of prisoners. Ethiopians, for example, are represented as slaves in the plays of Plautus and Terence. Slavery was widespread in the Roman world, however, and people of every color were unlucky enough to be subjugated indiscriminately. Both the Greeks and Romans recognized and theorized about the physical differences between themselves and other races, but attached no special stigma to color and were not racist in the modern sense.

Oil Lamps

"Fishbourne" and "Vintium" Oil Lamps

Roman

replicas: hand-crafted from original lamps at ancientlamps.com

date of the originals: mid-first century AD

provenance of the originals: unknown

description: Two terracotta oil lamps. Each: length 8.5 cm.

“Fishbourne” Oil Lamp (top)

This oil lamp is decorated with a common Roman motif - a cupid playing a flute while riding a dolphin. This image is widespread in the Roman world, having been found, for example, at Fishbourne in England. This lamp is the base for the “Vintium” lamp.

“Vintium” Oil Lamp (bottom)

This oil lamp is modeled after the same original as the “Fishbourne” oil lamp. It is decorated with another Roman motif, a cluster of grapes.

Selenus/Luna Oil Lamp

Roman

replica: hand-crafted from an original lamp at ancientlamps.com

date of the original: mid-1st to early 2nd century AD

provenance of the original: unknown

description: Terracotta oil lamp. This lamp is decorated with a crescent moon and a star, likely symbolizing the moon deity Selenus or Luna. Length 10 cm.

Provincial Factory Oil Lamps

Roman

replicas: hand-crafted from original lamps at ancientlamps.com

date of the original: 1st-3rd century AD

provenance of the original: S. France/N. Italy (Roman Gaul)

description: Two terracotta oil lamps.

Firmalampen (top)

Length 9.5 cm. This type of lamp, called a firmalampen, is a basic “factory” style mass produced in the Roman provinces. This undecorated example was produced in Gaul.

“Fortis” Firmalampen (bottom)

Length 9.75 cm. A firmalampen like the lamp above. This lamp was produced in Northern Italy. Factory lamps of this style often bore the maker’s mark FORTIS; this replica bears FIGVLI.

Inscriptions

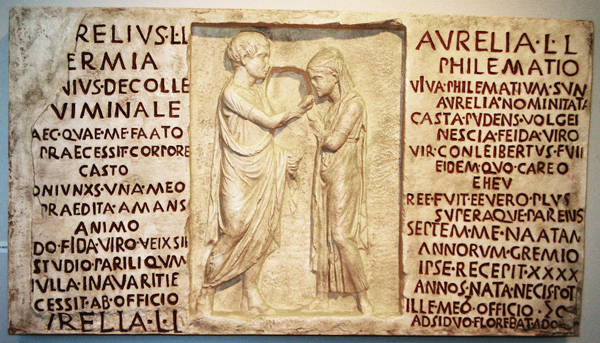

Funerary Stele of Aurelius Hermia and His Wife, Aurelia Philematium

Roman (Republican)

replica: from the British Museum, London

date of the original: 1st century BC

provenance of the original: discovered in AD 1593 in a tomb near the Via Nomentana, Rome; now in the British Museum, London

description: Stele depicting man and woman standing, facing in center. Inscription highlighted in red pigment to left and right. Plaster replica; Tiburtine stone original. Height 59 cm, width 104 cm, depth 8.5 cm.

The aspects of face and dress of the man on this funerary stele date it to the last century of the Roman Republic. The woman’s head and veil have been restored. She raises her husband’s right hand to her lips in a gesture of farewell, indicating that she has predeceased her spouse.

With abbreviations and lacunae (missing text) restored, the inscription reads, in translation:

Aurelius Hermia, freedman of Lucius, butcher of the Viminal hill. This woman, who has preceded me in death, chaste of body, loving of spirit, my only wife, lived faithful to her faithful husband with equal devotion since she failed in her duty out of no avarice. Aurelia Freedwoman of Lucius.

Aurelia Philematio, Freedwoman of Lucius. While I lived, I was named Aurelia Philematium, chaste, modest, ignorant of the rabble, faithful to my husband. My husband, whom I am without, alas, was freedman to this same Lucius. He was to me in fact and in truth more than and beyond a parent. He took me to his bosom at the age of seven years. At the age of forty years I am stronger than death. He flourished in the eyes of all due to my constant dutifulness.

The spouses in the inscription were freedpersons of the same patron, whose name was Lucius Aurelius. When slaves were freed in ancient Rome they usually took some form of their patron’s name as their own, hence Aurelius and Aurelia. Their former slave names, which indicate perhaps a Greek origin, are in this instance used as cognomina or last names. The dress and posture of both indicate their new status as Roman citizens. The inscriptions praise especially the qualities of the wife, qualities which conformed with those traits generally admired by the Roman upper classes: dutifulness and faithfulness, chastity and virtue. The man’s character is not so clearly defined--he has acted apparently as more than a husband, in fact, as more than a parent. This reference likely refers to Aurelia having been placed under the protection of the obviously older man while both were still slaves, since as slaves they could come to no legally binding relationship. Manumission would make their marriage possible and legal.

(See also: Funerary Inscription of Apuleia Crysopolis; Funerary Inscription of Nicella.)

Glass

Glass Unguentarium

Roman

original

gift of: Professor Thurston Lacalli

date: c. AD 100-200

provenance: purchased by donor in 1970-72.

description: Light green glass oil vial. Test tube shape with bulb bottom. On base: height 11.5 cm, diameter 2 cm.

Most unguentaria, used for the storage of perfume oils (see also: Nubian Boy Unguent Jar), are of this type: the “test tube” type, a common shape typical of the Flavian period. It is slender and tubular, with a faint constriction halfway down its length which marks off the neck from the body. The body itself is drop shaped.

It possibly was originally light blue-green in colour, but now has the yellowish film of decay. The body contains a pale ivory surface film, also the mark of decay.

(See also: Glass Jug.)

Glass Jug

Roman

original

gift of: Professor Thurston Lacalli

date: c. 300-400 AD

provenance: purchased by donor in 1970-72.

description: Light green/yellow glass jug with handle and trefoil lip. Height 10 cm, diameter 5.5 cm.

During the second and third centuries AD, the novelty of owning glass disappeared as glassware became more affordable. Therefore, a number of table and storage wares became popular and abundant, including plates, dishes, bowls, beakers, cups, bottles, jars and jugs.

During the fourth century AD, the style of jars and jugs changed, taking on exceedingly long necks (although ours is somewhat moderate) and pronounced funnel or bowl-shaped rims, which can be seen in this example.

Decoration on these household items was usually limited to spiralling threads or random blobs, either in the same colour as the vessel or in contrasting royal blue or turquoise blue glass. This jug has the decorative style of “snake-thread” ware. The thread, in the same colour as the rest of the jug, spirals gracefully around the neck, ending in what appears to be the head of a snake.

(See also: Glass Unguentarium.)

Blue Glass Amulet

Roman

original

gift of: Professor Thurston Lacalli

date: 4th century AD

provenance: purchased by donor in 1970-72.

description: Small bright blue glass amulet. Loop at the top for a chain or cord. Engraved. Height 4 cm, width 1 cm, depth 1 cm.

This original Roman blue glass amulet is made in the shape of a pendant and depicts a lion, crescent moon and star. It dates to the fourth century AD, a time when elaborate or brightly coloured jewelry was favoured. The imagery of the piece seems to suggest a link with Eastern art, though its provenance is unknown.

(See also: Bronze Amulets; Faience Amulets; Scorpion Amulet.)

Metal Crafting

Surgical Instruments

Roman

replicas

gift of: Albert David Mason

date of the originals: 1st century AD

provenance of the originals: House of the Surgeon, Strada del Consulare, Pompeii

description: The city of Pompeii, located a few miles south of Naples in Italy, was a large city by ancient standards. Destroyed and buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79, Pompeii has since been extensively excavated by archaeologists.

The city had been considerably Romanized from the 1st century BC onwards, and by the time of its demise, was a prosperous market town, port and industrial centre where Romans and local families lived side by side.

These instruments are accurate replicas of five surgical instruments found in the so-called House of the Surgeon (or Physician) in the Strada del Consulare in Pompeii. The house was discovered during excavations in 1818. A large number of medical instruments uncovered there, now housed in the National Museum of Naples, led to the conclusion that it was a physician’s house.

#1: Shears

Shears, called forfex by the Romans, were used regularly for cutting hair before a medical procedure was undertaken. Celsus, who lived in the reign of Tiberius (AD 14-37), tells us that cutting hair was also sometimes considered in itself a therapeutic treatment.

It is possible the edges of shears in the ancient world were never able to be made sharp enough to be of use in surgery. However, apparently Celsus occasionally used shears in the treatment of abdominal injury:

When all [the intestines] have been returned, the patient is to be shaken gently, so that of their own accord the various coils are brought into their proper places and settle there. This done, the omentum too must be examined, and any part that is black and dead is to be cut away with shears.

A large number of shears have survived from ancient times, the majority made of steel. This pair was made of bronze.

#2: Cautery

This instrument, called a ferrum candens (literally “glowing iron”) by the Romans, was usually made of iron, and of bronze in special cases. (Because iron deteriorates easily, few iron cauteries have survived from the ancient world.) This tile shaped bronze cautery was heated and then used for various purposes: as a counterirritant--an agent for producing irritation in one part of the body to relieve pain or inflammation in another part; as a haemostat--applied to treat bleeding vessels in order to stop haemorrhage; as a bloodless knife; and to destroy tumours.

In the early sixth century AD, Aetius composed a medical treatise which he compiled from earlier records; he described one of the uses of the cautery:

I put the patient lying on her back, then I incise the sound part of the breast outside the cancer and burn the incision with cauteries until the eschar [scab] produced stops the flow of blood. . . the first cauterization is for the sake of stopping the haemorrhage, the second for eradicating all traces of the disease.

#3: Elevator or Lever

This instrument, called a vectis by the Romans, was a bone lever used for levering a fractured bone into place or raising a depressed bone. The surfaces at the ends were ridged for better gripping. It is also possible this instrument was used for levering out teeth. Paul of Aegina, a writer of the sixth and seventh centuries AD who compiled medical knowledge from ancient times, wrote a description of a bone lever:

. . .on the first day before inflammation has come on, or about the ninth day after inflammation has gone off, we may set [bones] with an instrument called the lever. It is an instrument . . . about seven or eight fingers breadth in length, of moderate thickness that it may not bend during the operation, with its extremity sharp, broad and somewhat curved.

#4: Knife

Roman surgeons used many different kinds of knives. This particular knife is a phlebotome, called phlebotomus or scalpellus by the Romans. It was a type of lancet used for venesection, the opening of veins. The practice of bleeding a patient was one of the most common treatments for ailments. Celsus described the technique:

. . . if the scalpel is entered timidly, it lacerates the skin but does not enter the vein; at times, indeed, the vein is concealed and not readily found. . . the vein ought to be cut half through. As the blood streams out its colour and character should be noted. For when the blood is thick and black, it is vitiated, and therefore shed with advantage, if red and translucent it is sound, and that blood letting, so far from being useful, is even harmful.

The phlebotome was also used for opening abscesses and puncturing cavities containing fluid, and for dissection. The point of this particular phlebotome has a guard below it so that it cannot cut too deeply.

#5: Bone Forceps

These forceps, called ostagra by the Greeks, were specifically used on bones. Paul of Aegina described one of their uses:

If the bone is strong it is first to be perforated with the drills called abaptista and the fractured bone is to be removed in fragments, with the fingers if possible, if not, with a tooth forceps or bone forceps.

Soranus of Ephesus, who lived in the reign of Trajan (AD 97-118) used bone forceps to remove pieces of the skull after impaction of the foetal cranium. Bone forceps may also have been used for extraction of arrow or lance heads from wounds; the grips on the tips of the forceps would make grasping such objects easier.