Beginning around the third century AD, artistic sensibilities embarked on a gradual change as well. The influence of Christianity predominates in the art of the period, leading to a strong emphasis on spiritual and symbolic, rather than realistic and naturalistic, themes. Christian artists chose to reject the classical ideals of perfection in form and technique. Rather, they sought to present images which would draw the spectator into the inner eye of their work, emphasizing its spiritual significance. Men and women were no longer represented as images of physical perfection. Instead, their appearance was nondescript; their function was to represent historical or biblical characters in symbolic tableaux from the Old or New Testament. The principles of perspective were abandoned in favour of a hierarchy of scale in which privileged figures were greater in size.

Sculpture

Constantine the Great

Late Antique

replica: from the Louvre, Paris

date of the original: c. 350 AD

provenance of the original: discovered in 1864; formerly in the Campana collection; now in the Louvre, Paris

description: Colossal draped bust of a man placed on a small pedestal. Symbolic or spiritual portrait of the Roman Emperor Constantine I, who ruled AD 306-337. Plaster replica; white marble and alabaster original. Height 104 cm, width 79 cm, depth 42 cm.

Under Constantine the Great (see: Coins of Constantine I), as sole ruler (AD 324-337), Christianity became legal. This is a symbolic representation of Constantine rather than a portrait (see for comparison: Trajan; Livia; Gaius or Lucius Caesar; Hannibal). The upward-turned eyes with unnatural emphasis on iris and pupil suggest a spiritual gaze, one not of this world.

Constantine I was declared Emperor of the Western half of the Empire in 306 C.E. by the troops of his deceased father, the late emperor of the West. Because he was not the only general to make a claim for this title, it wasn’t until 312 C.E. with his defeat of Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge that he was the sole ruler of the West. Constantine’s conversion to Christianity began at this battle, when contemporary historians report that before the battle he received a vision from God showing him the Chi-Rho with the message “In this sign you will conquer” in Greek. His conversion was followed by the propagation of the Edict of Milan in 313 C.E., which officially decoupled paganism from the state and made Christianity a legal religion with the right to build and own churches as property. Licinius, Constantine’s co-emperor to the East who had agreed to this Edict, eventually returned to persecuting Christians in the East, giving Constantine a precedent, reinforced by other conflicts, to invade his co-emperor and become the sole ruler of the Empire.

Apotheosis of a Great Orator

Late Antique

replica: from the British Museum, London

date of the original: c. 450 AD

provenance of the original: Rome; now in the British Museum, London

description: One leaf of a diptych showing the three stages of apotheosis. Resin replica; ivory original. Height 29.5 cm, width 11 cm, depth 1 cm.

The Apotheosis of a Great Orator (previously identified as an emperor) is one half of a fifth century book cover. Representative of pagan revival under the Christian empire, such panels were sometimes given as mementos to consuls entering office. The illustration indicates that Roman worship of heroes and emperors had not disappeared from the religious consciousness of the masses. The deification of an emperor, or of his genius (spirit), had been prevalent in the Roman Empire. It had a dual purpose: first, deification legitimized the emperor’s authority to rule by linking his majesty with higher powers; second, it focused religious sentiment throughout the empire on the cult of the emperor. This ensured the continued loyalty of the more remote regions of the Empire to the political fortunes of Rome.

The word apotheosis is derived from a Greek verb which means “to make a god”. This panel shows a great man, an orator, rising towards heaven with the assistance of two genii. The man in the illustration is probably Quintus Aurelius Symmachus (c. AD 340-402). The dual images of the man and the signs of the zodiac on the upper right hand corner indicate a sympathy for Mithraic beliefs in life after death. The four-horse chariot on the podium next to the two eagles are symbols of the sun-god Helios and his ascent to heaven. The monogram at the top means “Symmachorum.”

The beholder participates in the great man’s apotheosis as the illustration draws the eye upwards through the four levels of images.

Ivory Pyxis

Late Antique (Christian)

replica: from the British Museum, London

date of the original: c. 600 AD

provenance of the original: Alexandria, Egypt; now in the British Museum, London

description: Small resin cylindrical pyxis lacking base and lid, illustrating scenes from the martyrdom of Saint Menas. Resin replica; ivory original. Height 12.5 cm, diameter 12 cm.

A pyxis, or box, was used to hold incense or relics. This pyxis has lost its cover, bottom, lock and hinge. It features scenes from the tragic martyrdom of the fourth century AD Egyptian saint, Menas (see also:Pilgrim Flask). St. Menas was an Egyptian camel driver who joined the Roman army and was martyred under the emperor Diocletian around AD 303.

The illustration begins with a prefect seated on a stool flanked by a guard and a scribe. Then comes Menas’ execution--the executioner grabs the saint by the hair and raises his sword. An angel appears on Menas’ left to receive his soul after death. Menas is then depicted as an orant (a stock figure of the martyr) with a halo, lifting his hands and eyes heavenward, declaring his faith while pilgrims approach. Finally, he stands under an arch, representing his sanctuary; two supporting columns are flanked by camels.

Casket Panels

Late Antique (Christian)

replicas: from the British Museum, London

date of the originals: early 5th century AD

provenance of the originals: now in the British Museum, London

description: Two of four panels from a casket depicting Christian religious themes. Resin replicas; ivory originals. Each: height 7.5 cm, width 10 cm, depth 1.5 cm.

Condemnation of Christ and the Denial of St. Peter (top)

Death of Judas and the Crucifixion of Christ (bottom)

This panel contains one of the earliest known depictions of the crucifixion of Christ. Mary and John stand to the left of the cross, a Roman soldier to the right. On the far left of the panel, Judas hangs himself. The cross and the tree are clearly out of proportion to the size of the figures. A correct representation would have required excessive, undesirable shortening of the characters because of the restricted space.

Oil Lamps

North African Oil Lamp

Late Antique (Christian)

replica: hand-crafted from an original lamp at ancientlamps.com

date of the original: late 5th century AD

provenance of the original: North Africa

description: This terracotta oil lamp bears Early Christian symbolism: a Latin cross near the spout and three triangles/dots on the shoulder, perhaps representing the Trinity. Length 10.5 cm.

"Chi-Rho" Oil Lamp

Late Antique (Christian)

reproduction: from the catacombs of San Callisto

date of the original: unknown

provenance of the original: unknown

"Icthys" Oil Lamp

Late Antique (Christian)

reproduction: from the catacombs of San Callisto

date of the original: unknown

provenance of the original: unknown

Inscription

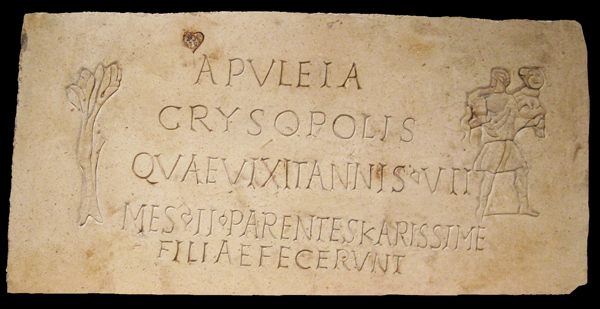

Funerary Inscription of Apuleia Crysopolis

Late Antique (Christian)

replica: by stonecarver Rob Assie

gift of: Dr Robert and Lura Mae Sider

date of the original: c. 3rd or 4th century AD

provenance of the original: catacombs of San Callisto, Rome

description: Stele with Latin inscription. Marble replica; marble original. Height 41 cm, width 85 cm, depth 8 cm.

This marble inscription, found in the catacombs of Rome, is a funerary stele or slab which was placed across the opening of aloculus, or slot-type grave. The inscription translates as follows:

Apuleia Crysopolis, who lived for seven years, two months; [her] parents made [this] for their dearest daughter.

Most burials in the catacombs do not bear inscriptions; those that do can be difficult to interpret. Whether Early Christian or traditionally pagan Roman, the inscriptions follow standard Roman formulas. However, there are often Christian clues in the form of phrases such as bene merenti (“to the well deserving”) and quiescet in pace (“rest in peace”).

This particular inscription betrays no overt Christian tendencies in its language. The surname Crysopolis, however, indicates that the child was from a Greek family which had lived in Rome long enough to give her a Latin first name. The letters are roughly chiselled, indicating that perhaps the family was lower class and unable to afford better.

A “Tree of Life”, a common Early Christian symbol, is depicted at left; a “Good Shepherd” bearing a ram is at the right. The image of the “Ram-Bearer” was a traditional Greco-Roman motif representing either Orpheus or the god Hermes (see: Hermes with the Infant Dionysus). The Christians in Rome adopted the symbol (as they did with other elements of the lexicon of traditional Greek and Roman art) and it became widely used to represent Christ; the ram was eventually replaced with a lamb. The motif’s appearance here indicates that the inscription, and thus the child and her family, were probably Christian.

(See also: Funerary Inscription of Nicella; Funerary Inscription of Aurelius Hermia and His Wife.)

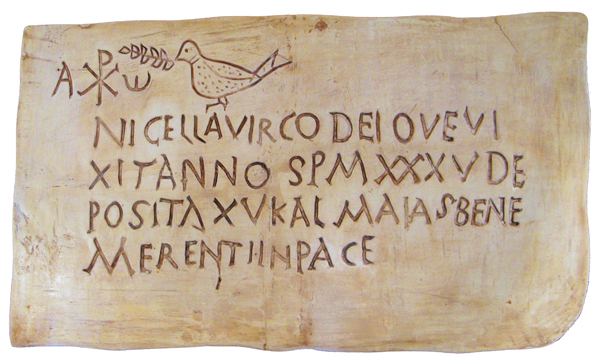

Funerary Inscription of Nicella

Late Antique (Christian)

replica: by artist Carrie Allen

gift of: Carrie Allen

date of the original: unknown

provenance of the original: catacombs of San Callisto, Rome

description: Stele with Latin inscription. Plaster replica; marble original. Height 37.5 cm, width 64 cm, depth 3 cm.

This marble inscription, found in the catacombs of Rome, is a funerary stele or slab which was placed across the opening of aloculus, or slot-type grave. The inscription translates as follows:

Nicella, God’s virgin, who lived for more or less 35 years. She was placed [here] 15 days before the Kalends of May [17th April]. For the well deserving one in peace.

There are Christian clues here in the form of the phrases bene merenti (“to the well deserving”) and in pace (“in peace”). The inscription also includes some overt Christian symbolism: the symbols for Alpha, Chi Rho, and Omega (see: "Chi-Rho" Oil Lamp), and a dove holding an olive branch.

(See also: Funerary Inscription of Apuleia Crysopolis; Funerary Inscription of Aurelius Hermia and His Wife.)