MAKING ART OUT of junk and scraps of images found on the Internet might not be everyone’s idea of an international exchange, but that’s exactly what Tim Nowlin brought with him to China.

Nowlin, head of the Department of Art and Art History, has been making collages by hand ever since he can remember. Thanks to a new exchange program with the Hubei Institute of Fine Arts (HIFA), he is sharing his passion for collage with students in Wuhan, China.

Nowlin was first invited to China in May 2016 to teach a three-week course in the HIFA printmaking department. The school’s 8,000 students study the fine arts on a new campus in the Hubei provincial capital of Wuhan, a city of 10 million people in central China at the intersection of the Yangtze and Han Rivers.

The city is a “real urban centre, a fabulous city,” says Nowlin, who calls his two trips there among the most rewarding teaching experiences he’s ever had. “I just loved the city and the school.”

By happy coincidence, Xiao Han, an art student in the MFA program at the U of S, was a native of Wuhan and accompanied Nowlin to China as his translator. She also helped negotiate arrangements with the school and even curated two or three shows of student work as part of the exchange.

“I can’t speak Chinese, so she was a godsend,” says Nowlin. “Language was a huge barrier. I had Xiao with me at all times translating so I was able to communicate with people easily, quite fluently, with her help.”

“They are all highly skilled and highly trained in drawing and painting and sculpting. So if you have an idea, you draw it out,” Nowlin explains. “They couldn’t figure out why I would make them make these collages out of recycled materials.”

To help his students understand what art made with junk and old scraps of paper was all about, Nowlin began with a lecture on collage in 20th-century art. He introduced work by renowned western artists such as Kurt Schwitters, Hannah Hoch and Robert Rauschenberg, all of whom collected discarded materials, cut them up and put them back together to produce new works.

“[Collage] was produced in direct response to advances in technology and industrial production,” Nowlin explains. “We live in a society now that, unlike 200 years ago, produces all this waste product... there is way more paper, way more garbage, way more everything. Artists began utilizing that, so collage art is really the first form of eco-art.”

The term bricolage, says Nowlin, was popularized in contemporary culture studies by French structural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss. A bricoleur does all manner of tasks using only the materials on hand, repurposing society’s cast-off items to give them new meaning. In today’s terms, we would call them tinkerers or do-it-yourselfers.

“Lévi-Strauss distinguishes between two ways of knowing the world,” explains Nowlin. “One is scientific thought that relies on abstract thinking and deductive reasoning, but that’s not where people dwell all the time. The other belongs to what he calls the bricoleur…. In Lévi-Strauss’s view, [bricolage] is all about contingency… things that you can’t predict, which is the world that we live in.”

Digital bricolage

Nowlin’s own expansion into digital art began in 2013 with an Insight Development Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council for a collaborative project entitled Bricolage and Digital Memory. The funding allowed him to purchase a top-of-the-line 9900 Epson inkjet printer and a graphic scanner, and to hire two graduate students from the Department of Computer Science to mentor him on the more technical aspects of the project.

The intent was to explore through research and artmaking how the digital experience transforms our sense of self, our memories and our relationship to art, and where it may be leading us as a culture.

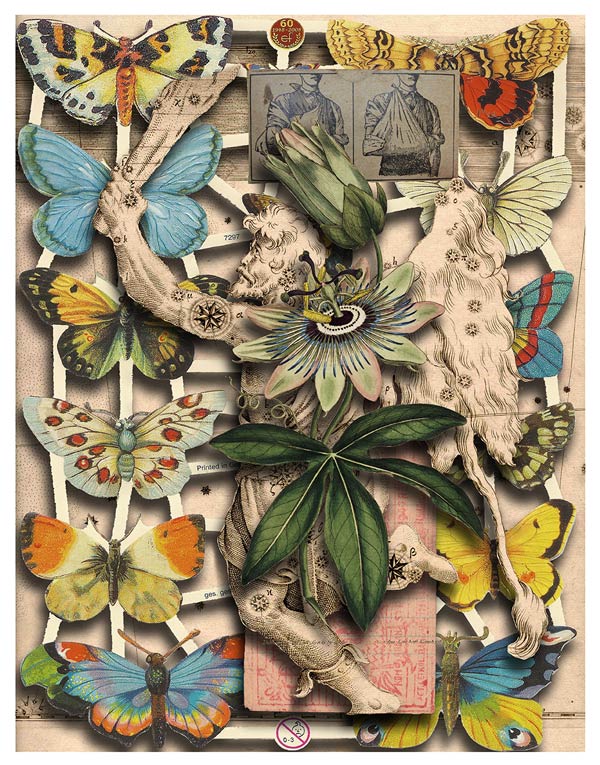

Nowlin began to make entirely digital collages by artfully putting together images from the Internet using tools such as Photoshop. During the course of the project, Nowlin amassed an archive that he draws from to create digital collages that include everything from old taxonomies of flowers and butterflies to scraps of text and paper.

With help from the computer science students, he also created a new app called the Bric-o-browser that attaches itself to websites and takes screen shots at set intervals. As the website content changes, the collages on Nowlin’s computer also change. But he soon realized that the resulting collages were not as interesting as his originals.

“The experience made me realize that all collage has a human filter to it. Bricolage has to have a human imagination at the centre of it… that’s how we associate things as human beings.”

A recent convert to digital media himself, Nowlin is sympathetic to his students’ early doubts about this new way of working.

“Everybody is a little bit suspicious of digitality,” he says, “although we, of course, use those tools to help us all the time. In my background as a printmaker, there was always the sense that a handmade print is a lot more beautiful or a lot more valuable than a machine-produced print. People associate the digital printer with commercial printing, but they do make beautiful, beautiful prints.”

People are people

Despite expectations that Chinese students would be different than his Canadian students, Nowlin was struck by how much “people are people.” The students he met in China have the same hopes upon graduation as his Canadian art students. They would like to work as designers, exhibit in commercial and public galleries or become teachers and professors. One difference, he notes, is that because of the intense competition to get into art school, students are very aware that they have to work very hard to be noticed.

“I felt like I really made a difference as an artist and a teacher. Everyone had a genuine appreciation of what I had to offer, and were really responsive to the ideas and the concepts in the talks, and the work that my students produced.”

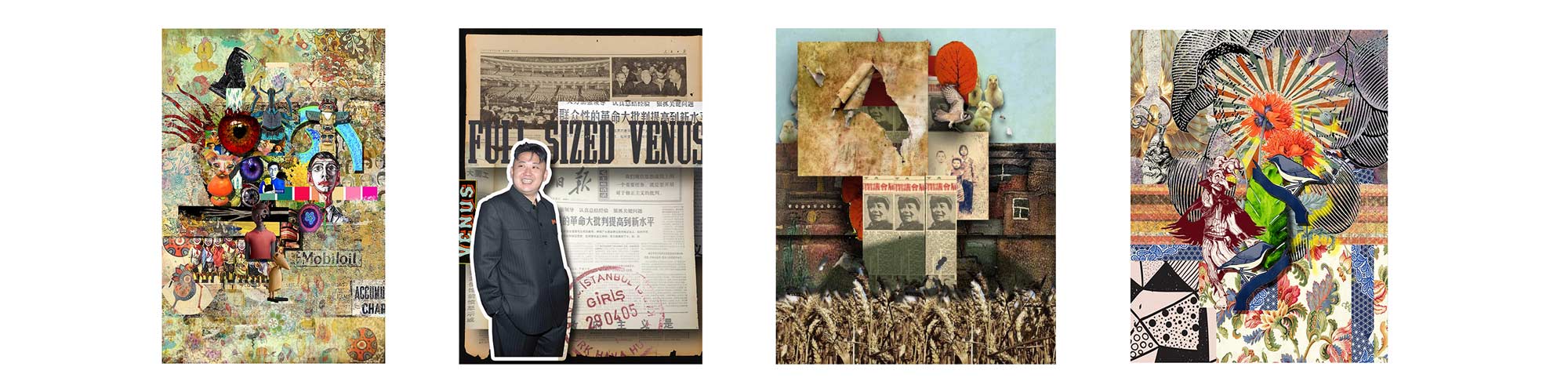

One student, a girl called Lin Jia Yi, was especially confused by Nowlin’s first assignment. By the end of the first day, he says, she had made a beautiful collage.

“When we put our show up, Yi was so happy, she was really proud of herself. She did really beautiful work. And she said to me, ‘I can’t stop making collage and it’s because I realized that the whole world is a collage.’”