DAVID KATZ IS NOT your typical first-year student. After 30-plus years in business and the civil service, Katz (BSc’73, MSc’80) has returned to the world of lectures, essays and exams in pursuit of an encore career.

He sees it as a chance to parlay his wealth of knowledge and experience into new opportunities. “I asked myself, how do I take what I know and what I’ve been doing and turn it into some value that I can contribute?”

And in choosing to study applied and professional ethics in the Department of Philosophy, Katz is delving into the moral principles that govern behaviours and activities in a way he never could in his work life.

A lifelong Saskatoon resident, Katz earned degrees in computer science and began his career as president of Custom Computing Systems, the province’s first retail computer store. In 1988, he moved into the provincial civil service, to what was then the Department of Science and Technology. There followed a dizzyingly complex series of department mergers, spinoffs and name changes, with Katz finally emerging as chief policy and science officer with Innovation Saskatchewan, a position he has held since 2011.

“I sat in the same seat and had a dozen departments evolve around me,” he says. “I have quite a stack of old business cards. I’m the continuous thread and that was completely unanticipated, but do any of us have the career we thought would develop?”

In his role, Katz is responsible for policy matters affecting innovation, including policy development. He is also the lead author of the Saskatchewan Framework for an Innovation Economy, a document that informed the development of Innovation Saskatchewan.

As he contemplated his impending retirement, Katz says he felt “the not-unreasonable concern” about finding meaningful and stimulating post-work activities, firmly believing that “keeping your brain active is a big part of keeping yourself from just idling.

“It occurred to me that there’s free tuition for seniors at the U of S, (but) if I took advantage of that, what would I do? What suddenly emerged was, I have done science and technology policy for most of my career in government and there’s always been an underlying assumption of the ethics of what we’re doing. Wouldn’t it be fun to peel the layers back on that, to understand how you come to positions on the ethics of things? What are the fundamentals of ethics that inform support for biotechnology or nuclear power or whatever it might be?”

He found exactly what he was looking for in courses offered by the Department of Philosophy.

Katz took his first class in the fall 2016 term, an introduction to ethics and values, and he is not shy about admitting he worried about being a student again. “It’s a coat I haven’t worn in a very long time.”

Shifting gears to book learning, adjusting to the kinds of interactions that occur in a first-year class and accepting he looks nothing like his young classmates took some time, “but I’d say it’s improving.”

Lines in the sand

Katz says the courses he is taking have highlighted that “just about everything we trip over has ethics in it. I hear a news report and think, that’s not a news report, that’s an ethical question…. It confirms that this will be a rich place to go.”

As an example, he points to the latest advances in gene-editing technology, in particular a recent report from China about its use on healthy human embryos. It is clear the implications require serious ethical consideration.

“The slippery slope argument to that is, being able to edit human DNA leads you to either creating non-humans or leads you down the path of eugenics. So is there an ethical limit to the application of (gene editing)?” asks Katz.

Society, he continues, must decide where “there’s a line that should not be crossed” when considering both benefits and pitfalls of scientific and technological advances. “I think ethics contributes to the discussion.”

Katz argues that individual members of society—not just scientists or the universities and funding institutions that support research—have a role to play in deciding the ethical lines in the sand. One ethical debate that the public has been weighing in on concerns autonomous vehicles, and while Katz says the implications of driverless cars are more complex than portrayed in mainstream media, future potential owners should be taking note.

Commentary on autonomous vehicles often raises the trolley problem, a well-known thought experiment in ethics, says Katz. Here is the trolley problem most often posed: in an emergency, the vehicle must make a choice between plowing into a group of pedestrians or ramming into a building, potentially injuring or killing the driver. Which should it choose?

“This is a classic problem… and one that people can relate to very easily.” Katz’s hope is that it opens up conversations about other ethical considerations related to technology. “Yes, there’s ethics in autonomous vehicles, there’s ethics in nanotechnology, there’s ethics in pretty much any endeavour in science. Hopefully, what we ultimately get to is a rational position that informs the decision to do or not do whatever it is.”

His point is that ethics is a “participatory sport,” but playing requires asking questions and thinking critically. While not everyone need delve into the topic as deeply as he has, Katz sees a benefit in offering ethics classes at university “to sensitize students. At least it would plant some ideas and enhance discussions with professional ethicists or ethics committees going forward.”

Staying engaged with the world

As he wraps up his own first-year classes and thinks about what comes next, Katz has become acutely aware that this area of study garners a good deal of attention from various quarters.

“I have a fear,” admits Katz, before relating a cautionary tale.

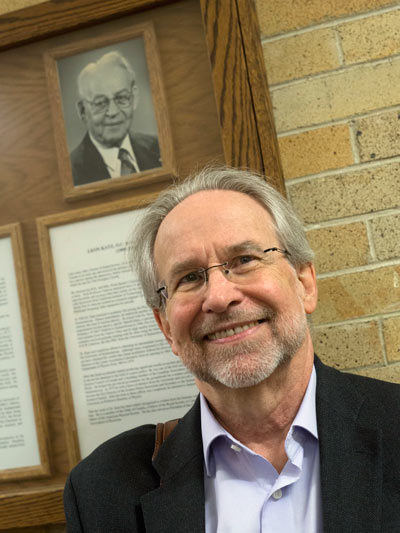

Katz’s father, Leon, was an accomplished physicist who once headed the Department of Physics at the U of S and is credited with, among many other achievements, bringing the first linear accelerator—precursor of the synchrotron—to campus. After he retired, though, the senior Katz gave up intellectual pursuits. “For about three years, it literally was kind of scary to visit. He’d tell you the same story two or three times in an evening because there was nothing going on.”

Then chaos theory came along, “and it was like a whole blood transfusion for him.” The elder Katz studied it, published papers about it and lectured internationally on the subject. “The result was that he had this new vitality that literally kept him being a scientist until the day he died. It was a real lesson that when you quit being engaged in thinking or having something intellectually challenging, I think you start to deteriorate, you start to wallow.” That is a circumstance Katz is determined to avoid.

Katz is looking forward to the freedom afforded by retirement—“I will stipulate ethics isn’t the only thing I’m doing; I have other interests as well”—including the chance to indulge his academic interest.

“It’s more a question of how I take my life experience and my incremental knowledge of ethics and turn it into something that will be exciting to pursue, and in some way contribute back.”