Every student of arts & science hears them. Campus myths are modern folktales that embed themselves into the bricks and stones of a place. These stories might be the longest-running experiment at the University of Saskatchewan: a 107-year demonstration of how the simple act of repeating a story morphs true history into something quite different—but far more interesting.

English student Braden Hursh spent his final term as an undergraduate combing through archival materials, talking to witnesses and historians, and tracking down the true stories that lie behind some of the most famous college myths.

Archival images courtesy of University of Saskatchewan, University Archives & Special Collections

First flight of the Airplane Room

Did Second World War pilots throw paper airplanes into the Thorvaldson Building’s famous ceiling?

DESIGNED IN 1913, the Chemistry Building—now called the Thorvaldson Building—was not completed until 1924 due to disruptions related to the First World War and the economic constraints that followed. The associations to wartime and the sheer age of the building make the Thorvaldson Building a breeding ground for myths.

The most enduring legend surrounding the building states that the paper airplanes lodged in the 68-foot domed ceiling of Thorvaldson Room 271 were flung there by Second World War pilots-in-training. When the pilots went to war, the legend says, their family members would periodically visit the Airplane Room—as it became known—to see if their loved one’s plane remained stuck. If a plane fell from the ceiling, it meant that the man who put it there would not be coming home.

Wartime pilots did receive training at the U of S campus through cadet programs and the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, although there is no record as to whether they trained in Room 271, now called the Henry Taube Lecture Theatre.

For many years, students have attached messages or objects to paper planes and flung them up to the ceiling, where the planes stick in the material lining the dome. Student graffiti on the wooden desks of Room 271 dates back as far as 1933, but the paper airplanes are a different story.

During the removal of asbestos from the ceiling in 1995, the original planes were taken down. Wayne Eyre, editor of On Campus News at the time, carefully unfolded each of the 366 airplanes but found nothing relating to the war; instead he just found what he calls “a lot of pranky and dopey comments.” The oldest date written on any plane was 1961. Other planes appeared older as they were brittle and yellow with age, but lacked dates.

The airplanes brought no closure to the myth, but the building’s records might. According to the 2013 U of S Heritage Register, the asbestos lining Room 271’s ceiling was a later addition to reduce echoes from the original hard surface of the dome. The ceiling was bare tile or plaster until at least 1950, well after the end of the pilot training programs. It is unlikely that anyone—even ace pilots-in-training—could have stuck paper airplanes into a tile ceiling.

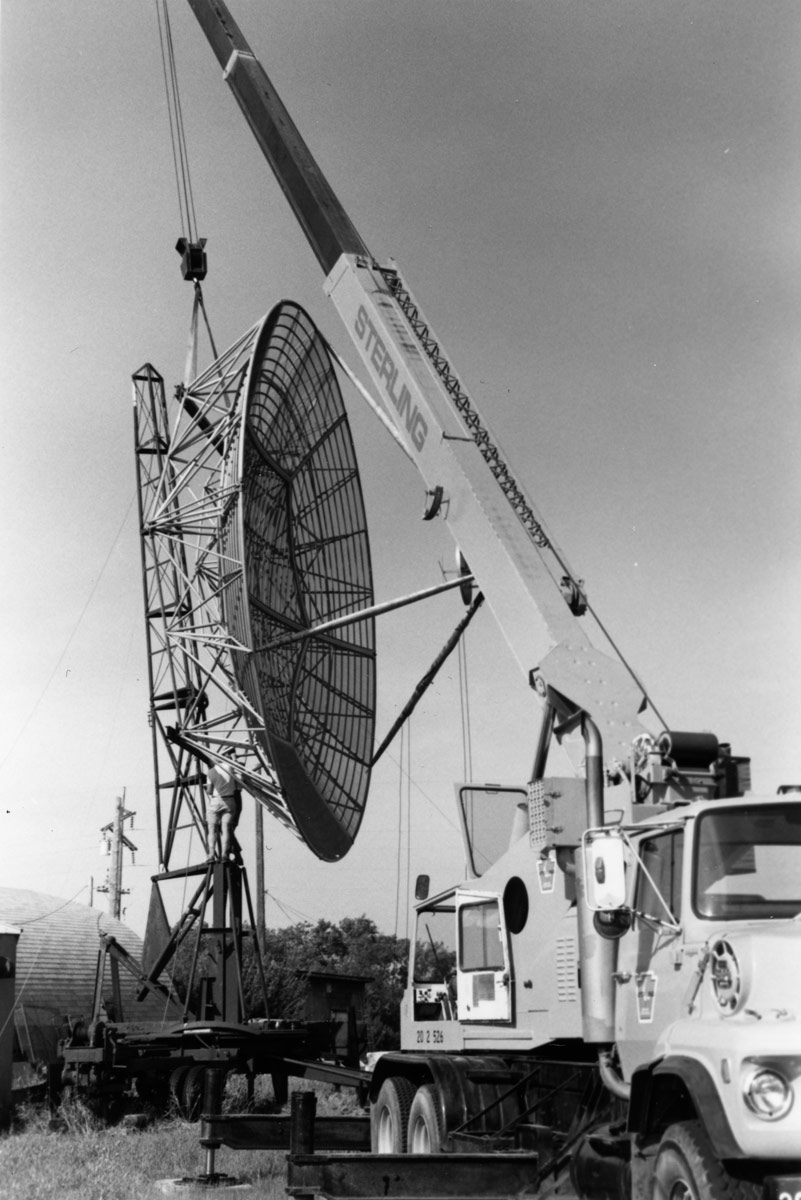

The Pearl Harbor radar

Was the radar that detected the Japanese attack found five decades later at the U of S?

ON DEC. 7, 1941, an SCR-270 radar located on the coast of Oahu, Hawaii picked up a large echo coming from the north. The soldiers operating the radar station reported the approach of an “awful big flight” to their commanding officers, but were told to disregard the disturbance. The contact they ignored turned out to be the impending attack on Pearl Harbor by the Imperial Japanese Navy—an attack that inevitably brought the United States into the Second World War.

According to one widely believed account, there is a direct connection between this piece of history and the University of Saskatchewan. The story goes that around 1990, an American museum was actively searching for the Pearl Harbor radar to add to its collection. The U of S, upon being contacted about the search, compared serial numbers from the original Hawaiian radar to a radar it had been using for atmospheric research. They were a match; the Pearl Harbor radar had sat forgotten on the U of S campus for half a century.

Some major pieces of this story are true. The United States military did send a radar—an SCR-270—to the U of S following the Second World War for the purpose of studying the Northern Lights.

“The aurora borealis causes interference that could theoretically be used to mask oncoming aircraft,” explains George Sofko, professor emeritus of physics at the U of S. “The United States was worried that the Soviet Union would be able to perform a sneak attack on American soil by flying through the aurora.”

In 1990, after years of groundbreaking research using the radar, the U of S shipped it to the National Electronics Museum in Linthicum, Maryland, where it remains proudly displayed today.

The U of S radar was an exciting find for the museum because SCR-270 radars had become extremely rare by 1990, says Alice Donahue, assistant director at the National Electronics Museum. “Most of the remaining models had long since been sent away to other developing countries for their military use.”

But was it the radar that detected the Pearl Harbor attack?

“The radar that was sent to the U of S was a (newly built) version of the same type of radar that detected the Pearl Harbor attack, but it was not the exact same radar,” Donahue says.

So what happened to the real Pearl Harbor radar? An investigation published in IEEE AES Systems Magazine in 1994 tracked it to a U.S. Air Force radar station in Wakkanai, Japan, where it was kept in service until becoming obsolete. It was scrapped in the mid-1950s.

Learn more:U of S researchers used the SCR-270 radar to conduct some of the world's first radar-based research on the aurora. This work continues through the Super Dual Auroral Radar Network (SuperDARN) headquartered at the U of S. Learn more at the SuperDARN website. |

The Lady in the Well

Does the victim of a century-old murder mystery haunt the Archaeology Building?

IN 2006, DURING the excavation of an abandoned well in the Sutherland area of Saskatoon, a construction crew unearthed a heavy barrel. Upon inspection it was revealed that the barrel held a woman who had been murdered, stuffed into a gunny sack and tossed into the unused well almost a century earlier.

Dubbed “The Lady in the Well,” this unsolved murder remains Saskatchewan’s oldest known cold case. According to campus myth, forensic work on the Lady was performed in the basement of the Archaeology Building and her spirit remains there to this day. Students in the building often speak of lights turning on and off and the sound of footsteps echoing through the basement.

The Archaeology Building has housed various disciplines throughout the years, including crop science, medical science and, most recently, archaeology and anthropology. Due to the building’s age, along with the fact that it once housed a functioning forensic and educational morgue, the Archaeology Building has gained a reputation as the most haunted building on campus.

Although there is no longer an active morgue in the building, the remains of one still lurk in the basement. “Part of the original morgue facility is buried under the parking lot on the west side of the building,” says professor and forensic anthropologist Ernie Walker. “The inside entrance to that small room was cemented over during the renovations to the building.”

Walker, however, is quick to debunk any rumours of The Lady in the Well haunting the Archaeology Building. He personally conducted all of the forensic work on the remains of the unidentified woman at an off-campus hospital. Therefore, if the Lady in the Well’s spirit still walks the Earth, it is probably not at the University of Saskatchewan.

Bite-sized myths: true or false?

The Airplane Room has lead shutters on the windows because it was meant to be used as a bomb or fallout shelter. |

False. The shutters are steel, not lead, and were likely designed simply to block out light.

The Airplane Room has spooky acoustical properties—mysterious dead zones and spots where a whisper can be heard from across the room. |

True. Like in many large rooms built with curved surfaces, reflections and interference patterns cause soundwaves here to behave in unintuitive ways.

Thorbergur Thorvaldson is buried in a block of concrete outside the building that bears his name. |

False. Thorvaldson is buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in Saskatoon, and the concrete block wasn’t installed until years after his death.

Someone is encased in that concrete block, but it’s actually Jimmy Hoffa. |

False. Probably. Mind you, we haven’t actually checked…

The designer of the Murray Library forgot to account for the weight of the books, and the building would collapse if it were full. |

False. Variations on this myth are told on campuses across Canada. The extra space in the library was built to allow the book collection to grow.

While laying the cornerstone for the College Building in 1910, Sir Wilfrid Laurier gashed his head on the stone. |

False. A report on the ceremony printed in The Globe the following day made no mention of any head injuries, but said that Sir Wilfrid went on to deliver an “eloquent address” at a large meeting that evening.

A ghost named Hank haunts the Department of Drama and must be appeased with offerings of marshmallows. |

Who knows? If Hank is real, he is a well-travelled ghost. He apparently moved with the department from the old Hangar Building to the current John Mitchell Building.

There is a secret tunnel between the Arts and Education buildings. |

True—sort of. A walkway tunnel was started in the 1960s, but the project ran out of funds. The two unconnected ends of the tunnel, which were intended to meet in the middle, are now used for storage.