Playing to learn and translating history

Benjamin Hoy examines historical portrayals of Indigenous people in board games and the use of games as a tool for teaching

By Eden Friesen

The shelf above Benjamin Hoy’s desk in his Arts Tower office is lined with glossy boxes rather than books. Here is a space in which work and play intentionally overlap.

“Games help translate historical lessons into tin and pasteboard that children can play,” said Hoy, assistant professor of history at the University of Saskatchewan and author of two upcoming papers that examine historical and contemporary uses of board games.

“I started liking history—loving history—because I played games,” he said. But games are more than just fun to Hoy, the winner of a 2017 Provost’s Outstanding New Teacher Award. He understands them as a tool for education.

“I'd love it if historians were the main way that people learned about history,” he said. “But we're not.”

Hoy’s recent work revolves around how people in the past used games to teach culture, politics and history, and how games today are used for similar purposes. He sees games as a medium that “adults often use to translate the past into a format children can experience and understand. In general, a child is not likely to go to war, but they can play the war and in the process learn about their culture.”

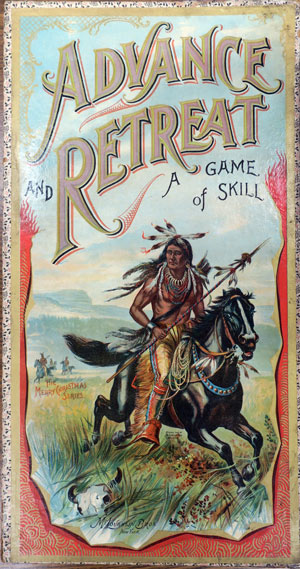

In an upcoming paper titled “Cardboard Indians: Playing History in the American West,” Hoy focuses on the representation of Indigenous North Americans in historical board games from around the world. He examines games as one of the methods through which children have been taught “the underpinnings of American culture.”

“Long before many 19th-century American children interacted with Indigenous communities, they were seeing advertisements that depicted them, they were playing with toys or they were playing games,” said Hoy. “That is one of the most interesting things about looking at games for kids. Children have very limited experiences, and games provide some of their first exposure to ideas about race.”

Part of Hoy’s research for the project involved a fellowship at the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester, N.Y. in 2016 where he had the chance to play century-old board games himself.

“It was wonderful, in the sense that I didn’t realize there were museums of toys,” he said. “Every day, walking through a museum where kids are screaming and having fun is a very different experience than a normal archival trip.”

As well as studying the historical use of games as tools for teaching children, Hoy sees great potential for games in a university classroom. He is currently publishing a paper about his experiences constructing games to make dull or misunderstood subject matter more accessible to students.

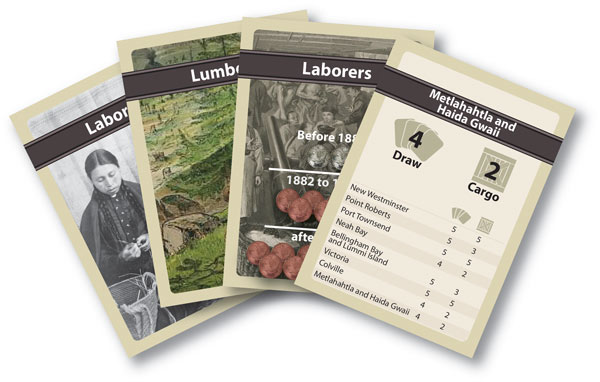

One of these challenging subject areas is smuggling across the 19th-century Canada-United States border. “When students are reading about smuggling, their first impression tends to be, ‘Those people are criminals. I would never do something like that.’ And that makes it very hard to understand the historic setting,” said Hoy.

Hoy’s solution was to design a board game in which some players take the role of customs agents and others play as merchants. Based on archival records, the game offers merchant players strong incentives to smuggle goods.

“I don’t think there’s a single person who’s played the game who hasn’t chosen to smuggle,” said Hoy. The experience becomes a memorable lesson about “how historic context can shape decisions.”

Hoy’s work on games as teaching tools, both historically and in a contemporary setting, is just the most recent in a lifetime of passion for learning through play. “I love history and I love games,” he said. “I love showing students the ways you can use history to understand the world you live in.”

The two papers will be published in upcoming issues of Western Historical Quarterly and Simulation and Gaming.

Eden Friesen is an English student intern in the College of Arts and Science communications office.