Sask. researchers help crack mystery 518 million years in the making

A fossilized worm found in the Chengjiang Biota. (Xiaoya Ma)

A fossilized worm found in the Chengjiang Biota. (Xiaoya Ma)

A new paper co-authored by University of Saskatchewan researchers shows the creatures responsible for one of the world's oldest and most complete fossil records lived more turbulent lives than previously thought.

The group of fossils — known as the Chengjiang Biota — deposited in Yunnan, China is 518 million years old.

The fossils are considered "the most complete snapshot of Earth's initial diversification, the Cambrian Explosion," says the paper, recently published in Nature Communications.

The marine fossils provide a glimpse into a time when life on Earth was undergoing dramatic changes.

"What we have here is sort of a snapshot of those really diverse communities that were evolving in shallow marine environments, around 520 million years ago," University of Saskatchewan geology professor Luis Buatois said in a phone interview.

Buatois is one of the paper's co-authors.

"We can call them worms in general, then there is a wide variety of arthropods, including trilobites, that were extremely common in what we call the Early Palaeozoic," he said.

"Even some of the earliest vertebrates were there; so what we are talking about here is what we call the Cambrian Explosion — which is the rapid appearance of the basic body parts of most animals."

While the fossils themselves have been extensively studied, the researchers focused on the environment where the creatures lived, previously believed to be a relatively stable, deep-water environment.

However, the researchers found this was far from the case.

By analyzing a core sample from the area, the research team found the animals were instead swept deep into the ocean from a river delta — a more challenging, unpredictable habitat, according to Buatois.

"They had to be able to survive there and that's kind of a big departure from previous ideas," Buatois said.

"The animals have to live with a series of stress factors, like for example, very rapid sedimentation, discharges of freshwater, or water turbidity."

The research team's findings offer fresh insight into the lives of animals that were entombed long before dinosaurs ever walked the Earth.

"When you are working with fossils, you need to first understand where they are preserved and then you have to evaluate if they have been transported or not," Buatois said.

"It seems these animals that we have always thought were adapted to a very stable low-energy environment — they were actually living closer to the shoreline."

The international team responsible for the paper also included researchers from Yunnan University, the University of Exeter, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the University of Lausanne, and the University of Leicester.

By applying the team's methods, Buatois said long-held notions about other fossil sites could be upended as well.

"I don't think that we will end up reinterpreting everything as shallower water, but the picture that is emerging is that these sort of (animals) were actually living in a wide variety of environments."

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Senate expenses climbed to $7.2 million in 2023, up nearly 30%

Senators in Canada claimed $7.2 million in expenses in 2023, a nearly 30 per cent increase over the previous year.

Pedestrian, baby injured after stroller struck and dragged by vehicle in Squamish, B.C.

Police say a baby and a pedestrian suffered non-life-threatening injuries after a vehicle struck a baby stroller and dragged it for two blocks before stopping in Squamish, B.C.

Tom Mulcair: Park littered with trash after 'pilot project' is perfect symbol of Trudeau governance

Former NDP leader Tom Mulcair says that what's happening now in a trash-littered federal park in Quebec is a perfect metaphor for how the Trudeau government runs things.

Demonstrators kicked out of Ontario legislature for disruption after failed keffiyeh vote

A group of demonstrators were kicked out of the legislature after a second NDP motion calling for unanimous consent to reverse a ban on the keffiyeh failed to pass.

RCMP uncovers alleged plot by 2 Montreal men to illegally sell drones, equipment to Libya

The RCMP says it has uncovered a plot by two men in Montreal to sell Chinese drones and military equipment to Libya illegally.

Government agrees to US$138.7M settlement over FBI's botching of Larry Nassar assault allegations

The U.S. Justice Department announced a US$138.7 million settlement Tuesday with more than 100 people who accused the FBI of grossly mishandling allegations of sexual assault against Larry Nassar in 2015 and 2016, a critical time gap that allowed the sports doctor to continue to prey on victims before his arrest.

BREAKING Canucks goalie Thatcher Demko won't play in Game 2

The Vancouver Canucks will be without all-star goalie Thatcher Demko when they face the Nashville Predators in Game 2 of their first-round playoff series.

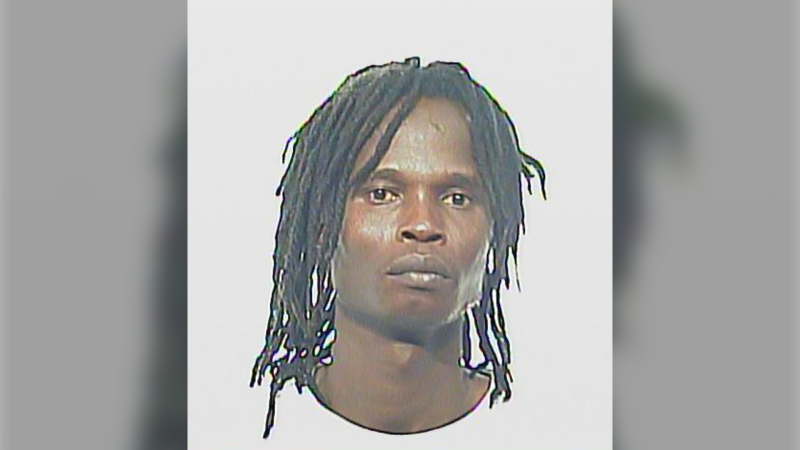

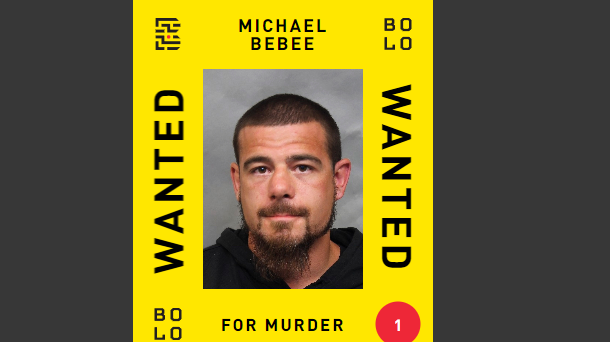

Man wanted in connection with deadly shooting in Toronto tops list of most wanted fugitives in Canada

A 35-year-old man wanted in connection with the murder of Toronto resident 29-year-old Sharmar Powell-Flowers nine months ago has topped the list of the BOLO program’s 25 most wanted fugitives across Canada, police announced Tuesday.

Doctors ask Liberal government to reconsider capital gains tax change

The Canadian Medical Association is asking the federal government to reconsider its proposed changes to capital gains taxation, arguing it will affect doctors' retirement savings.