‘We are all responsible for learning our collective history’: Art projects at USask encourage understanding between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people

Members of the university community and the wider public have engaged with artists on campus through USask’s Indigenous Artist-in-Residence program

Editor's note: The University of Saskatchewan (USask) art galleries are currently closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the USask art collection can still be viewed online at saskcollections.org/kenderdine.

By Shannon Boklaschuk

As Catherine Blackburn spoke about her artistic practice during an interview at the University of Saskatchewan’s Kenderdine Art Gallery in January, candid family photographs were projected on the wall behind her.

The pictures presented an intimate look at family life, showcasing a decades-old photo of Blackburn’s parents on their wedding day more than 40 years ago. Numerous pictures featured Blackburn’s late grandmother, with the matriarch seen beading at her home in Patuanak, Sask., in one scene; in another, slices of meat were hung to dry in the grandmother's kitchen—something that was once a common sight at her house.

That particular picture brought a smile to Blackburn’s face as she recalled the delicious pemmican her grandmother used to make for her—dried meat without berries, just the way she liked it. Another photo featured a group shot of Blackburn’s extended family; yet another depicted Blackburn’s great-uncle, a trapper, carrying a lynx.

The slideshow represented what is important to Blackburn and the central themes that influence her work: kinship, community, identity, language, culture, history, land and love. She wanted to feature the photos on the walls to give viewers at the gallery “an overall sense” of her practice.

“Also, the personal narrative behind my practice is important for them to acknowledge, because I think that leads into a bigger conversation of identity and perspectives on identities,” said Blackburn (BFA’07), a USask alumna who studied studio art in the Department of Art and Art History in the College of Arts and Science.

“I think it’s important for people to recognize that this practice just doesn’t come from nowhere; there’s very specific reasons for why I chose beadwork, why I’m choosing textile work. They can kind of get a sense of that by understanding my family history or my story.”

A member of the English River First Nation in Treaty 10 Territory, Blackburn was born in Patuanak, Sask., of Dene and European ancestry. A multi-disciplinary artist and jeweller who now lives in B.C., her practice is centred on contemporary interpretations of traditional Indigenous art forms, merging elements of traditional Dene culture with her experiences of living as an Indigenous woman in the modern world. Her work has attracted local, national and international attention; for example, she was included on the longlist for the 2019 Sobey Art Award—considered to be Canada’s preeminent contemporary art prize.

Blackburn sees working with beads as a form of resistance and as a means of reclaiming identity and sovereignty. She describes her hands as holding ancestral connections, exemplifying “how Indigenous bodies hold power and resurgence.”

“Not so long ago, this very art form was banned by missionaries and the federal government as a tactic of assimilation—just as all other art forms of song and dance, along with prayer and language, were,” she said. “Indigenous identity was affected to its very core.”

Today, Blackburn is looking at Indigenous identity through the lenses of her own lived experience as a woman on Turtle Island in the year 2020. She notes that culture is always evolving, and she acknowledges this change as she seeks to honour the past. On Jan. 30, for example, during a performance at the Kenderdine Art Gallery, Blackburn was gifted a traditional Indigenous marking by artist Stacey Fayant. Blackburn chose to honour her eyes by receiving markings on each side of her head in Dene syllabics, with a floral pattern from her late grandmother, paying tribute to her family history. The performance, titled Skin Stitched, involved using a needle and thread to stitch permanent ink into Blackburn’s skin.

This blending of the past and the present is evident through all of Blackburn’s work. Blackburn talks about the relationship between beadwork and using her body as a tool, honouring the “ancestral connection that refers to a cultural history of love and exchange.”

“We are here because of the strength, ingenuity and love of those that came before us, surviving off the land using their hands in the same tactile way to protect and honour each other,” she said. “Oftentimes I will bead with thoughts of someone, or concentrate on who I am making it for and what it represents. In this way I am beading for someone and beading is a medicine. It holds immense love.”

Through a collaboration with the University Art Galleries and Collection, Blackburn participated in a one-month residency on campus that ended on Feb. 7, 2020. During the residency, visitors were encouraged to visit the Kenderdine Art Gallery and engage with her as she created new works for her solo exhibition with these hands, from this land, curated by fellow USask alumna Leah Taylor (BFA’04).

As a curator at USask, Taylor believes art has a significant role to play in helping people understand the lived experiences of others.

Taylor gives credit to the influential Indigenous artists who are doing, living and presenting this difficult work; for example, through her role at the USask galleries, Taylor has had the opportunity to work with artists and fellow USask alumni such as Lori Blondeau (MFA’03), Ruth Cuthand (BFA’83, MFA’92), Wally Dion (BFA’04) and Joi T. Arcand (BFA’06). In 2019, Taylor curated Arcand’s exhibition she used to want to be a ballerina, which was on view at USask’s College Art Gallery II. Arcand—who was shortlisted for the Sobey Art Award in 2018—described the show as a “celebration of Indigenous girlhood.”

“I believe art is one of the most powerful tools for expressing ideas that relate to lived experience,” said Taylor. “My interest as a curator has focused on politically and socially engaged contemporary art. I believe that artists are typically the first to challenge social constructions that need to be refigured or deconstructed. Artists are willing to take risks, especially with difficult and challenging subjects, by presenting new or diverse perspectives for viewers to consider. As a curator, I help to frame this work for the public.”

Members of the university community and the wider public have recently had the opportunity to engage with artists on campus through USask’s Indigenous Artist-in-Residence program. Initiated by the University Art Galleries and Collection in 2018, the new program aims to recognize and honour the contribution of Indigenous artists, craftspeople and knowledge keepers and create awareness and appreciation of Indigenous ways of knowing and being.

In 2019 and early 2020, renowned Plains Cree artist Ruth Cuthand served as artist-in-residence, offering beading instruction in various buildings on campus. Lyndon Tootoosis, a stone carver and storyteller from Poundmaker First Nation, joined the USask community in January 2020 as the newest artist-in-residence; he began by gathering together students and members of the broader community to learn the names and stories of the 13 Nehiyaw lunar phases, laying the groundwork for a collaborative carving project at USask’s Gordon Snelgrove Gallery during Indigenous Achievement Week in February.

When jake moore took on her new role as director of the University of Saskatchewan Art Galleries and Collection in the summer of 2019, she was pleased that Indigenous representation and engagement were cornerstones of Galleries Reimagined—USask’s restructured approach to the visual arts on campus. She sees USask’s Indigenous Achievement Week art projects and the new Indigenous artist-in-residence program as ways to engage in Reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people (or, more specifically, “Conciliation”—trying to come to a point of agreement—a term used by Métis professor and art critic David Garneau).

“By bringing forward Indigenous ways of working in the arts, by sharing existing space like the University Collection, the walls of our public buildings and the regular programming stream in our galleries, we will start to put into symmetry the relation between Indigenous artistic works and cultural production and those that continue to bolster and celebrate the Western canon,” said moore, who also serves as a faculty member in the College of Arts and Science’s Department of Art and Art History.

Under her leadership, moore said the galleries will consciously act upon the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the 94 calls to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). USask’s main campus is located on Treaty 6 Territory and the Homeland of the Métis.

“The ‘truth’ part of the TRC is one Canadians seem to be having the hardest part with,” said moore. “For the University Art Galleries and Collection to accept our responsibilities of both representing and forming culture, we need to hold space for the multiple voices of this territory and listen to what is made clear in humility and gratitude. How we perform as an instrument of the larger institution in this transitional time can model behaviours for relations based on reciprocity.”

Woodland Cree artist Vanessa Hyggen (BA’17), a USask alumna who works as the executive assistant to the Vice-Dean Indigenous in the College of Arts and Science, has witnessed firsthand how art can foster understanding between people with different lived experiences. She has been involved in two Indigenous Achievement Week art projects on campus that have aimed to spark conversations about decolonization and Indigenization.

During USask’s Indigenous Achievement Week in 2019, Hyggen worked with Cuthand on a project called mîkisak ikwa asiniyak ǀ Beads and Stone ǀ Lii rasaad aykwa lii rosh (written in Cree, English and Michif). The creation of the piece began by breaking a slab of Tyndall stone, a type of dolomitic limestone from Manitoba that is featured on numerous buildings throughout campus. The broken pieces of Tyndall stone—symbolizing USask’s architecture—were then integrated with beadwork as a performative and visual step toward Reconciliation. The completed artwork is now installed on the second floor of the Arts Building, outside the hallway leading to the Dean’s Office and other administrative spaces.

Earlier this year, Hyggen and Dr. Sandy Bonny (PhD)—a literary and visual artist, geologist and team lead for the College of Arts and Science’s Indigenous Student Achievement Pathways (ISAP) program—proposed a project titled anohc kipasikônaw/ we rise /niipawi. The project, which saw Nehiyaw syllabics inscribed on 100-year-old slate stair treads reclaimed from USask’s Thorvaldson Building, evokes the 13 moons of the lunar calendar used by Indigenous peoples to guide their movements and life decisions. With 13 steps, each seven feet long, the project has an ambitious scale; a synchronicity of skillsets between Tootoosis, Bonny and Hyggen, and the engagement of diverse USask students eager to learn syllabics and to try their hand at stone carving, ensured its success.

“The wear patterns on the stones are from students and faculty coming and learning and sharing knowledge for 100 years—so this very western thought process,” said Bonny, who noted the steps were transformed “from being physically impacted by the people to inspiring thinking through an Indigenous knowledge lens.”

“It has a nice narrative shift for me that way.”

It’s through projects like anohc kipasikônaw/ we rise /niipawi that Hyggen believes art can help people understand each other’s lives and perspectives; as she points out, “anything can be communicated through art.”

“Art history shows us what societies have held in importance, what people’s belief systems were and are—from a fertility goddess, to the Last Supper, to Banksy’s street art,” she said. “All of these pieces can tell you so much by looking at the material used, the way the piece is used or displayed, how it was created, why it was created and, of course, the content of the piece. Many of my own pieces are northern landscapes; some of them discuss current politics. There’s a story in my choice of subject matter.”

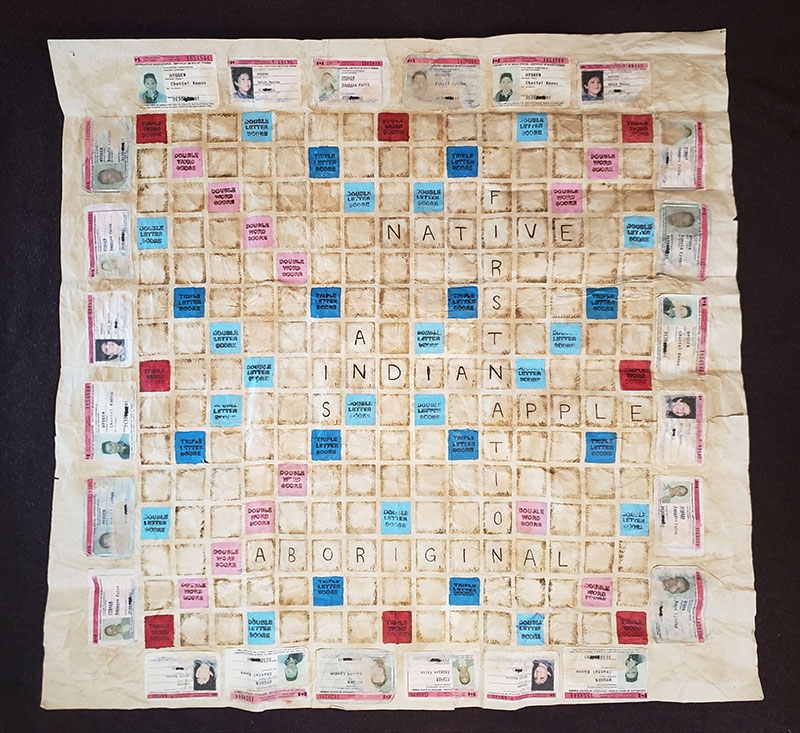

In her own artistic practice, Hyggen explores issues around identity and the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. Her artwork entitled is an indian, scrabble blanket, for example, features a square designed to look similar to a Scrabble board game. The border of the piece is created with status cards of her family members, and under the image on each piece of identification reads “is an Indian within the meaning of the Indian Act, chapter 27, Statutes of Canada (1985).”

“This is a piece which explores my identity—a blue-eyed, fair-skinned status Indian—and it also has special meaning to me because of all of the games of Scrabble I played with my kohkom,” said Hyggen. “But, it also has meaning beyond my own identity. When I first showed this piece, most people had not seen a status card, or had known that your status card expires.

“I want pieces like this to spark a curiosity that causes someone to look a little further,” she added. “Understanding the histories of treaties and the Indian Act are crucial to Reconciliation. These are the pieces of our collective history that have brought us to where we are today. We are all responsible for learning our collective history so that we can create a healthier and more prosperous future.”